Soldiers to this day carry lucky charms with them. The charm can be a letter, a photo, or some other small object. The writer of the article below, published in 1902, was absolutely astonished that British soldiers would carry charms and actually put faith in these items. People during that time period believed in “progress.” Superstitions were supposed to be left behind, but the truth is that people are naturally superstitious and need to believe in something to pull through horrible events, such as wars.

SOLDIERS BELIEVE IN CHARMS AND SPELLS

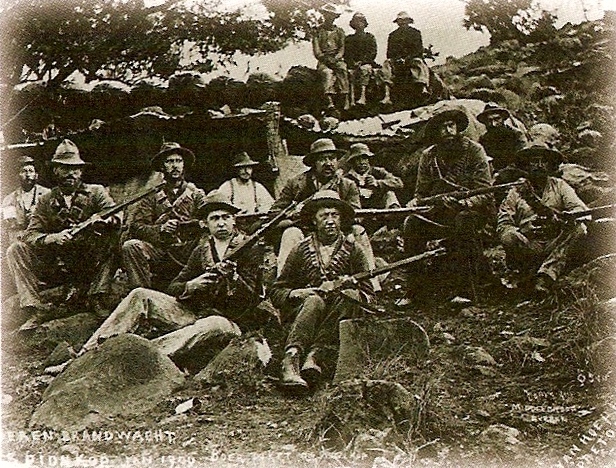

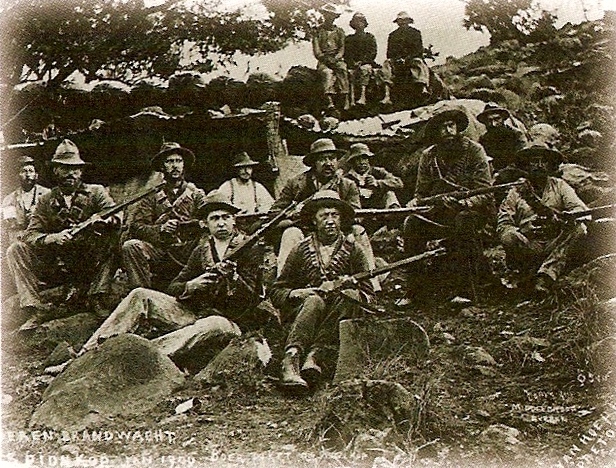

During the South African war [Second Boer War] a number of instances have cropped up showing that the idea still prevails that there are such things as charms and spells against wounds and death. Not long ago a paragraph appeared in some of the papers to the effect that a soldier’s watch, with a charm attached to it, had been found on one of the battlefields, and was being held for a rightful claimant. Earlier in the war a private’s letter told how a comrade had come in safety through a hot engagement by virtue, as he thought, of an amulet he wore, to be mortally wounded in a subsequent skirmish, when, by the merest chance, he was not wearing his charm. A relative’s letter from the front tells the writer of a young fellow who wore a charmed ring suspended from his neck. The wearer had it from his sweetheart; he placed the most perfect faith in it, and, though he had been in several hot corners, he had hitherto always come out scatheless.

Although this kind of belief is of very ancient date, it is curious as well as interesting to find it still in existence in the British army. Perhaps we ought to say “traces of it,” for it is hard to believe that it is widely prevalent. And yet it would not be very surprising if it were so, seeing that a certain proportion of the rank and file are illiterate, and come from a stratum of society which is largely superstitious. It is curious to compare our army in this respect with the German.

Those who happened to be in the fatherland during and immediately after the war of 1870-71 must have been struck by the amount of superstition that, hidden under ordinary circumstances, in the then excited state of the public mind made its way to the surface, much as the mud of a stagnant pool floats to the top when the water is agitated. Nothing seemed too absurd to be believed. Portents and warnings were seen everywhere. Black crosses, observed for the first time in windowpanes of the houses of the peasantry throughout Baden and the south generally, were held to be signs of divine wrath against the turn things in general had taken in the fatherland, especially in regard to the church. The excitement touching this phenomenon became intense, and was only allayed when a Baden glass manufacturer came forward and demonstrated that the warning crosses were marks imprinted on the glass in the process of making. [Source]