People have been waging labor strikes since, at the least, the time of the ancient Pharaohs. It was not something that was affiliated with a political party or something that “whiners” did to take advantage of business owners. Strikes have been carried out throughout history as a way to fight back against poor treatment, low to no wages, and awful working conditions.

Labor Strikes 3000 Years Ago Same as Today

A new translation of an ancient Egyptian record — hieroglyphics found on tablets buried at Thebes more than 3,000 years ago — gives the most interesting details about a labor stroke which occurred in the ancient capital when hundreds of workmen decided they were not being paid a sufficient quantity of corn and fish for their daily labors, and that their hours were too long and their overtime not generous enough.

Having reached this conclusion after a number of conferences between the workers and their “chiefs” (the modern walking delegate often being one of the “scribes”), the workmen notified their employers, who were the “great princes,” that they would work no longer until their wages were promptly paid and also a new wage scale was arranged.

The record reads almost as if it might be the history of a strike occurring yesterday — or today — taking into account, of course, the difference in the locale, the environment and the temperaments of the people 3,000 years ago.

The tablets were found in the excavation of some ruins at Thebes and are of great value in giving us a strong light on the social life of the antiquity, and particularly upon the labor conditions, of Thebes 1,200 years before Christ.

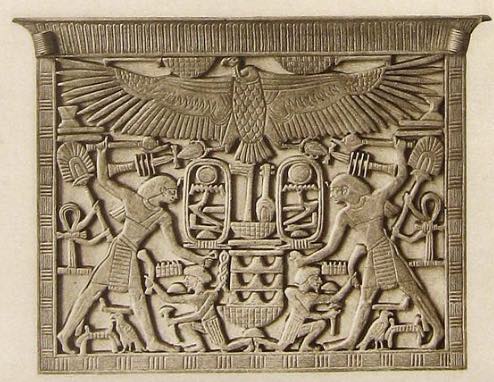

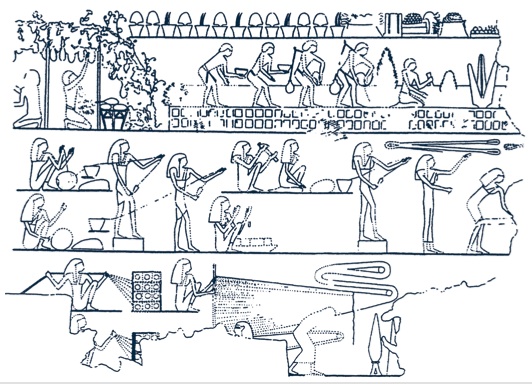

The translation shows that there existed at Thebes a large number of workmen employed in the erection of the necropolis. They were composed of metal workers, carpenters, artisans and similar craftsmen, who were always referred to by the officials — and of course the gentry of Thebes — as the crowd or “companies.”

At their head was a chief workman who resembled the foreman of our present day, and to him was interested — in addition to the overseeing of his men — the keeping of a daily journal showing the record of the laborers.

These reveal to us that the time sheet of today is no more than an elaboration of the daily recording of the workmen of ancient Egypt. There are even the same old excuses for absence from work — the word “ill” being entered the greatest number of times beside that of the man’s name; again, there would be that of “laziness” and occasionally the plea of taking a holiday in order to sacrifice to the gods, or because the wife or mother-in-law of the family suffered from some sickness.

This particular group of workmen was employed in the City of the Dead at Thebes during the reign of Rameses IX.

It is one of the acknowledged characteristics of modern Egypt today that payments of any description are never made without delay. This was true of ancient Egypt as shown in the translations. The routine of delays to which the workmen were subject was the greatest factor in the labor problem at that time. Many promises were made by employers, but very often months would pass before payment would be made, and the men practically were starved into resistance and striking.

The supply of corn was due on the 28th of each month; in the month of Phamenoth it was delivered one day late, in Phamuthi it was not delivered at all and the workmen went on strike or, as the Egyptians expressed it, “stayed in their homes” and refused to be coaxed by the scribes and priests to return to their work.

On the 28th of Pachons the corn was paid, but to the rage of the workmen only 100 pieces of wood were distributed for the entire number of men. Their patience becoming exhausted, they went in a body, taking their wives and children with them, to Thebes, and on the next day their appearance before the “great princes” and the “chief prophets of Amon” aroused great excitement in the capital.

Even as the modern committee of workmen today goes before the head of an industry, so did these men present their complaints and make their demands to the men who were next to Pharaoh. The result was that on the 30th of the month the great princes ordered the scribe to appear before them and ordered him to distribute the corn belonging to the government as rations to the workmen so that they would be inclined to return to their work on the necropolis.

The table shows this entry in connection with the strike at the necropolis:

“We received today our corn rations; we gave two boxes and a writing table to the fan bearer.” The meaning of the last part of the entry is that the boxes and the writing tablet were given to an attendant of the Governor as presents for persuading his master to settle the claims of the laborers.

The conditions were just as deplorable in the twenty-ninth year of Rameses III. The men were almost obliged to enforce the payment of their supplies of the food owing to them a “a strike of work.” On these occasions they left the City of the Dead with their families, thus emptying whole section of the town, and threatened never to return to work unless their demand were granted. Documents have been found showing that this state of unrest among the proletariat existed continuously for half a year. The month of Tybi passed without the people receiving their supplies. They must have been accustomed to such treatment, for they allowed another month to pass before taking any radical steps. Then they lost patience and on the 10th of Mechir “they crossed the five walls of the necropolis” and said: “We have been starving for eighteen days.”

They placed themselves behind the Temple of Thothmes III and refused to be moved from their sacred harbor of refuge. In vain the scribes of the necropolis and the two chief workmen tried to entire them back to work. They refused to move until their demands were granted — and the next day, the affair having assumed a threatening aspect, two officers of the police were sent to the place. The priests also tried to pacify the workmen, but their answer was “We have been driven here by thirst and hunger. We have no clothes, we have no oil, we have no food. Write to our Lord the Pharaoh on the subject and write to the Governor who is over us that they may give us something for our sustenance.”

Their resistance was successful and on that very day they received their provisions for the entire month. Peace reigned for a while and they worked steadily on the necropolis, but in the very next month their wages were again stopped and again they threatened to strike.

Source: The New York Herald. Newspaper. May 21, 1922.