This 1912 article about a “new” sort of vehicle covers an invention that appears to be almost like something out of a video game and was no doubt the inspiration for many hoop-track vehicles that came afterwords.

Fastest Things in World is the Aerounicycle

St. Louis, July 20. — “Merrily we’ll roll along, roll along,” 12 miles a minute, 720 miles an hour, 19,280 miles from sun to sun, in a hoop!

Get that right — in a hoop! That is what the speed maniac of the future may be doing.

The aero-unicycle is the last word in speed. It is destined to do for the racing auto and the speediest motorcycle what they did to old Dobbin.

“The only limit is a man’s ability to live while he travels, and an unobstructed roadway,” says Clinton Coates, inventor of the aero-unicycle.

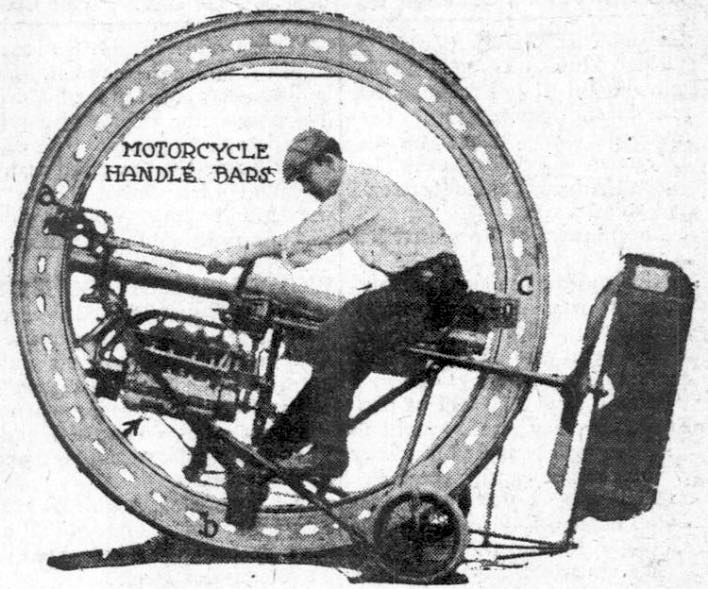

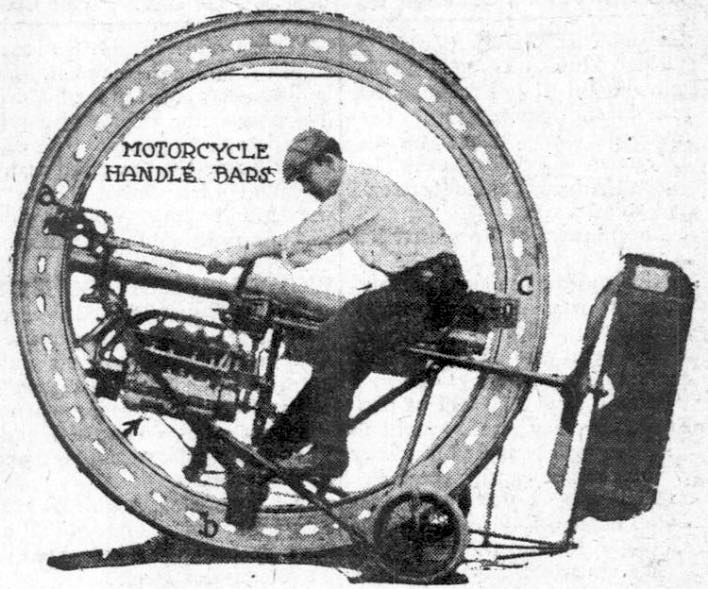

The machine is a freak. Inside a big aluminum hoop the rider is blown along by aeroplane propellers.

The hoop has an outside diameter of 81 inches, and an inside diameter of 67 inches. Around it is a pneumatic tire 1-3/4 inches wide. Along the inner rim of the hoop and on each side travel three sets of three rollers, or wheels, on ball bearings. These support the framework, the motor and the rider, and keep them level with the ground. There is no traction.

The propellers, 41 inches wide, having a forward thrust of 50 pounds with each revolution, blow the hoop along just as a boy with a stick knocks his hoop along the walk. The hoop is merely an endless, always revolving track upon which the rider travels.

There is a minimum of friction and air resistance to be overcome, and no power is lost in transmission.

Inside the hoop is a saddle for the rider, the motor and handles, with which are connected two wires leading to the steering rudder.

Coates and his co-inventor, W. McDonald, explained the workings of the aero-unicycle to me, and invited me out to the Catlin field to “see it roll.” At five in the morning, before the curious were awake, William Hunter, a professional motorcycler, rolled the unicycle out.

Hunter leaped on the saddle, started the motor (six horsepower) and Coates “cranked” the machine by turning the propeller. The hoop began to revolve, the rider and the machinery gliding along on the inner rim.

With three revolutions Hunter leaned forward on his saddle, thereby drawing up the two small wheels about a foot from the ground, and he was off. A mechanical counter of revolutions of the hoop told us he was rolling 55 miles an hour. He had the queer vehicle under perfect control, turning and stopping at will.

“The hoop will cover a mile in 250 revolutions,” said Coates, “and an engine capable of driving the hoop 3,000 revolutions a minute can be carried. That gives the machine a speed capacity of 12 miles a minute, or 720 miles an hour, a velocity at which no person could probably live, even with wind shields and oxygen tanks for breathing.

“There are these dangers: Striking an obstruction, getting one of the small ball-bearing wheels out of its track. Either one would mean a sure and sudden death to the rider. They are mere possibilities, though.”

Coates is a blacksmith; McDonald is a sidewalk contractor. Both are speed dreamers, and now they have a machine that looks good to make their dreams come true.

Source: The Day Book (Chicago, Illinois newspaper). July 20, 1912.