Can you imagine what the survivors of the Titanic felt after escaping death when so many others had died? Was their survivor’s guilt?

The article below gives an interesting account on what happened the fateful night, as experienced by both the third officer and the ship’s look out.

Third Officer and Look Out of Titanic Tell of Sinking of the Great Ship

Say They Lacked Marine Glasses, Which Would Have Made It Possible for Them to Steer Clear of the Floating Mountain of Ice

Washington, April 23 — The death cried of the 1,600 victims of the Titanic were brought to life again in the Senate building today.

Third Officer Herbert J. Pittman was on the stand before the Senate Investigating Committee.

He described the sinking of the great ship. He told of the prayers, the cried, the moans — the mighty chorus of woe that rose to heaven as the Titanic disappeared beneath the waters.

The British officer told his story in short, blunt sentences. His manner was almost stolid. But even his voice choked when he came to the death scene, and he begged the committee not to question him further along that line.

Frederick Fleet, one of the men who was in the crows nest of the Titanic when she struck the iceberg, followed Pittman.

Fleet told of sighting the iceberg, of reporting by telephone to the officer on the bridge, of the course of the Titanic being changed just a little — and then of the grinding crash.

The stories of both men were dramatic in the extreme. For both were men who realized that they might have done more than they did; that had they perhaps been more urgent, more clear headed, that awful disaster would not have occurred, or occurring, not have been so costly in human lives.

The Senate Committee room was jammed again today, and hundreds were refused admittance. Those who were present were mostly the wives of senators.

There were many times in the course of the stories of the officers of the ship that lies at the bottom of the Atlantic when the faces of the women went white, when their hands gripped the sides of their chairs, and the hot tears rose in their eyes.

A high wind that moaned and whistled through the cracks of the windows, and rustled through the room like the spirit of another world, added to the tenseness of the scene.

Haunting every man and woman was the word picture of the Titanic’s end drawn in Pittmans brusque short words.

Pittman began his story with the trials of the Titanic at Belfast, and then went on through the whole voyage up to the time of the accident.

“The collision woke me up,” he said. “It sounded as if we were coming to anchor.

“I rushed on deck. I saw nothing, and I went back to my bunk, believing I had been dreaming.

“Boxhall came to my room a few minutes later. He told me we had struck an iceberg. I got out on deck, and found boats being lowered. Moody told me he had seen ice on a forward lower deck. I went down, and saw a little.

“Then I saw firemen coming up with their bags.

“I saw a woman crawling painfully over a hatch, and I went out to help in loading the boats.

“I helped to lower boat No. 5, which was the one assigned to me before we sailed. A man in a dressing gown said, ‘You had better get women and children over here to load the boat.’ I found out later he was Mr. Ismay.

“I shouted ‘Are there any more women?’ There did not seem to be, so I let in some men. I jumped out of the boat again. I thought I would be more use on deck.

“There were 40 in my boat, including 6 men. There would have been no men, had there been any women to go.

“First Officer Murdock told me to go in charge of the boat. He shook hands with me, saying, ‘Goodbye old man, good luck.’”

The witness stopped. His face paled under the bronze of the sea. Then he added, in a lower voice:

“I never saw him again.

“I thought the Titanic had filled only two or three compartments and that she would float.”

“Did any person try to get into your boat after it struck the water?” Senator Smith asked.

“No, sir: none tried to get in or out of it. All behaved admirably. None of the women were permitted to row, although some of them wanted to in order to keep warm.

“It wasn’t zero weather — it was about 35 or 40 degrees. But it was chilly.

“We drew away from the ship, and I heard four reports. They sounded like big guns in the distance. I think it probably was the bulkheads bursting.

“I don’t think the boilers exploded. From where I was I could not see any people on the afterdeck as she went down. Everyone I saw on the ship had a lifebelt, except a few stray members of the crew.

“There were no explosions until the whole of the ship was submerged.”

“When you shook hands with Murdock, did you ever expect to see him again?” asked Smith.

“I certainly did.”

“Do you think he expected to see you again?”

“Apparently not. I thought we Would come back to the ship in a short time. I had no idea she was going down.”

Pittman said he saw no people in the waters after the Titanic sank.

“Did you hear any cries?” asked Smith.

“Oh, yes,” said Pittman, sadly.

“Crying, and sobbing, and moaning — and praying, too.

“I told my men to pick up a few more from the water. But the passengers in the boat begged me not to. They were afraid we would be capsized.

“I turned my boat around to row to the cried, but when I saw the passengers believed the swimmers would swamp us, I did not go back.

“We took out our oars and drifted for an hour.”

Pittman was pressed by members of the committee to give details as to his efforts to rescue people from the water.

“I would rather you would leave that out,” he said, his face white.

“I know you would,” said Senator Smith, “but we must know about this.

“That was all the effort I made to rescue people from the water,” replied Pittman, almost choking.

There was silence, broken only by the moaning of the wind, and the gasp of a woman for a few minutes. Then Pittman went on.

“We saw the Carpathia about half past three. She seemed about five miles away by her lights.

“Day was just breaking. All the cries and moans had stopped long before.”

Pittman was cross examined by several members of the committee as to how many persons the lifeboats could have held, and what condition they were in.

Fleet, the lookout, swore he could have sighted the iceberg that sent the Titanic to the bottom soon enough for the ship to have steered out of the way if he had had marine glasses.

“We asked for glasses at Southampton. We were told to ask Second Officer Lighteller. We were told there was none for us.

“I can not tell how long it was after I first sighted the iceberg to the time we struck.

“The berg seemed very small when I first saw it — about as large as these two tables.

“It got larger as we drew nearer. When we got alongside it was a little higher than the forecastle head.”

“How high is the forecastle head?” asked Smith.

“About 50 or 60 feet above the water.”

Fleet sat tearing at his fingernails, twitching his feet, and gazing at the floor. His replies were almost inaudible, and several times Smith was forced to ask the stenographer who sat near him to repeat the answers.

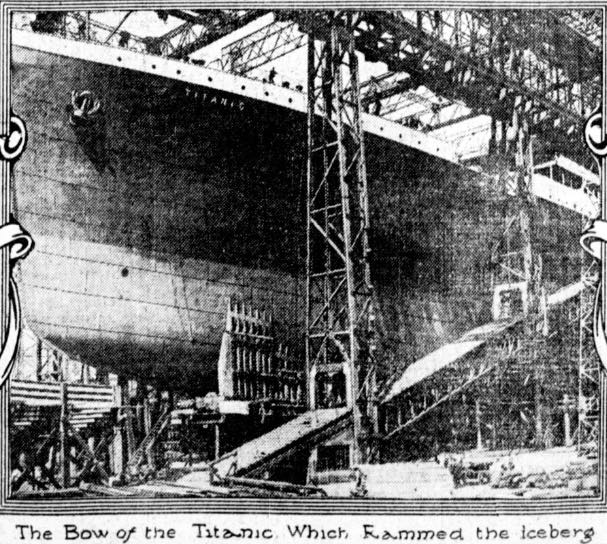

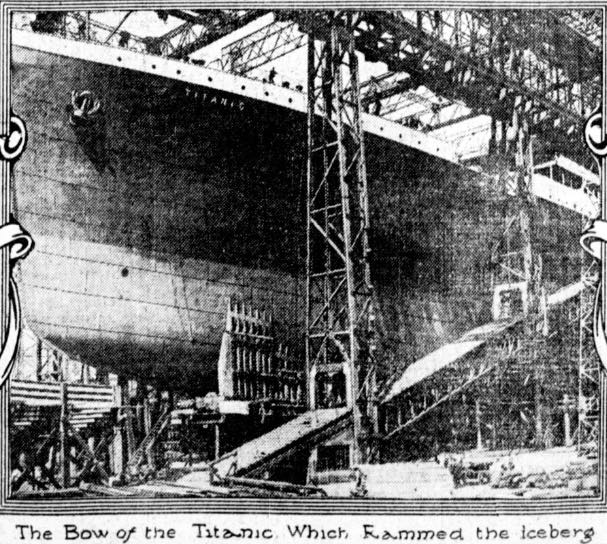

“I telephoned having sighted the iceberg,” he said. We started to go to port. We were making straight for the iceberg. We struck it on the starboard bow, just before the foremast, about 20 feet from the stem.

“There was a soft grinding noise — not much shock. Some ice broke on the forecastle deck, and some on the weather deck.”

Source: (1912, April 23). Third Officer and Look Out of Titanic Tell of Sinking of the Great Ship. The Day Book.