This report details a woman who, suspected of poisoning her family, took her crystal ball with her to jail. While it is common for murderers to make up crazy stories this one happens to be rather interesting given that seances and crystal balls were an underground trend in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Crystal Gazing and Poison in Murder Case

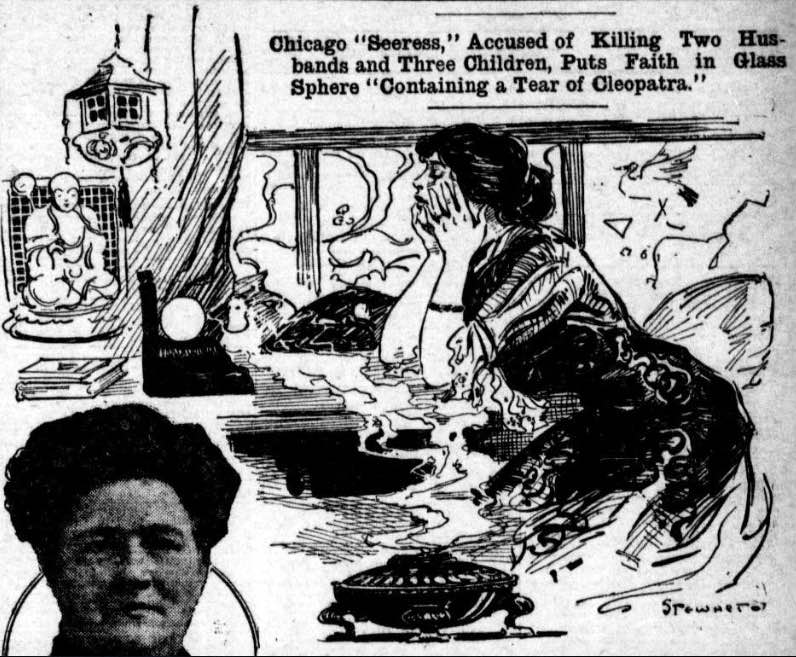

Equipped with a $500 crystal ball, containing — so she says — a tear dropped from the eye of the original Cleopatra. Mrs. Louise G. Lindloff, spiritualist medium and seeress, hopes to clear herself of the charge of murdering two husbands and three of her own children.

Five members of Mrs. Lindloff’s family have died in more or less mysterious fashion in the past seven years. Each carried a life insurance policy naming Mrs. Lindloff as sole beneficiary.

The five deaths netted the seeress $10,650.

When her son Arthur died the other day, apparently of poisoning, suspicions were awakened that led to her arrest on charge of murder.

She took her precious crystal ball with her to jail, and looked into it for the spirits of her dead.She says that she has communicated thus with Arthur, and that he tells her she will be exonerated, but that she is unable to get in touch with her late husband, Wm. Lindhoff [the newspaper spells their last names as both Lindloff and Lindhoff]. However, she is assured that Arthur will look him up.

The doctor who attended Arthur was the first to suspect foul play. He thought he detected symptoms of poisoning. The doctor he called into consultation agreed with him. They had the boy removed to a hospital, but it was too late. He died in a short time.

Then followed Mrs. Linndloff’s arrest. The subsequent inquiry developed the fact that she had collected insurance, not only on the life of her son, but on the lives of four other deceased relatives.

She protested her innocence, denying indignantly, that she ever kept poison in her house, but the police, on searching her place, found there rat poison, a box of mercurial poison and several other boxes labeled “Poison.”

But the accused puts her faith in her magic crystal ball. Through the “counsel” she gets from the spirit world through this ball, she rests assured that she will be able to prove her innocence. Every day she gazes into its mysterious depths, and reads there “messages” touching the future.

Her latest information is that she will be released before the month is over.

The police say that the magic ball is common glass and is worth intrinsically about fifty cents, but Mrs. Lindloff maintains that she paid $500 for it, and that its great value lies in the queenly tear that lies at its heart.

“That one tear enables me to read the future,” she avers. “When I gaze into the ball I see the tear at its center expand in size, and within I see what will come to pass in future years.”

Psychologists explain that the visions seen in such a crystal ball are “waking dreams,” and are spun out of the “subconscious mind,” when the ordinary consciousness is dulled by long gazing at the fascinating crystal.

****

“There are some people who cannot look into an ordinary globular bottle without seeing pictures.

“Crystal gazing seems to be the least dangerous and most simple of all forms of psychic experimenting. You simply look into a crystal globe the size of a five-shilling piece, or a water bottle filled with clear water, which is placed so that too much light does not fall upon it. You make no incantation; engage in no mumbo-jumbo business.

“If you have the faculty, the glass will cloud over with a milky mist, and in the center the image is gradually precipitated in just the same way as a photograph appears on a sensitive plate.” — Wm. T. Stead.

****

“These phenomena are quite as curious and important as those of radium. . . An ex-president of the folklore society has informed me that the phenomena entirely depends upon a disordered liver, to which I can only reply that, if that be so, I should be the chief of crystal gazers. The question can only be settled after many long series of experiments.” — Andrew Lang.

Source: The Day Book (Chicago, Illinois newspaper). June 24, 1912.