Have you ever wanted to stencil designs on woods, leather, walls, or fabrics? The article below, published originally in 1906, explains how this was done over a hundred years ago.

Stenciled Designs For Wood, Leather And Wall Treatments

Stenciling numbers conspicuously among the revived handicrafts taken up by women and offers a delightful field of experiment in a broad sense.

There are few homes wherein an artistic spirit prevails that stencil decorations in one form or another are not apparent. The application of this simple decorative treatment lends itself admirable for all manner of furnishings, imparting at it does a simple, yet effective and conventional mode of decoration that is neither ornate nor commonplace.

Stencils are applied to a number of surfaces, such as walls for frieze and side wall, or ceiling, wood work, leather, burlap, denim, linen, canvas, pongee and other fabrics, besides heavy papers of various sorts.

They are also variously applied to wooden and leather trimmed furniture, to window and doorway hangings, couch pillows and other essentials of interior decoration.

Stencil treatment is especially adapted for Mission interiors or those suggestive of the great artist-craftsman, William Morris.

In stenciling, as in many other handicrafts, one’s fancy may have free lance, and the more originality the worker possesses the more artistic and valuable her work becomes, though many persons with no knowledge of drawing may become expert stencilers as far as the technical part of concerned, and this is a big half of the question. The shops supply stencil patterns, but then they are apt to be copied by others, so that it is better for those who do not possess any ability to draw and improvise, to buy their patterns from artists who have a practical knowledge of the requirements in drawing stencils.

How to Cut and Design a Stencil

The amateur must first study the practical requirements of stencil patterns before boldly starting to design them. One of the first considerations to keep in mind is that the pattern must necessarily be broken up in small parts called “ties,” which hold the design together by means of narrow uncut strips. These little ties are, of course, an essential part of it and may be introduced in such a manner as to add character and individuality, rather than to take those qualifications from it.

Veins in leaves become a part of the ornament, while the flowers and trees are conventionalized after various artistic treatment. When you once familiarize yourself with the characteristic outline and botanical analysis, conventional treatment of the same becomes very simple and in this manner the designer will supply herself with the new ideas.

After the design is completed or copied, it should be traced off on paper, which comes especially for the purpose. Manilla paper is frequently employed.

Before proceeding to cut out the pattern, the paper must be oiled to render it non-absorbent when the pigment is brushed over in applying the design to the surface. A solution frequently employed for this purpose consists of equal parts of linseed oil and turpentine to which is added a quantity of Japan dryer, equal to one-sixth of the combined oil and turpentine. Any paint shop will mix this solution for you.

Next take a very sharp knife with which to cut out the design proper, remember not to cut the little links or “ties” which hold the design together. The pattern may be placed upon an even piece of board or glass. A piece of white plate glass two feet long and a foot wide is ample enough for any purpose. A thin coating of shellac put on the stencil protects it from the wet pigments employed in applying the colors.

When the stencil is carefully cut, place on the intended surface in the correct position, place your left hand firmly upon it and with the right dip brush in the pigment and pass over the stencil. When this is removed a distinct and clean cut pattern will appear upon the face. When the same stencil is applied in a repeat or continuous pattern the pigment must first dry before proceeding with another.

When more than one color is employed in the stencil, care must be exercised that the wrong color is not allowed to run or spot the section not intended for it. Of course this comes with practice and when villigence is exercised.

Individual Pigment

The beginner should consult one experienced or the paint shop man before applying pigments promiscuously on any sort of a surface.

Ordinary house paints may be applied for stenciling purposes on plastered walls that have been painted one color, and the same stencil patterns may be used for plastered or calcimined walls with decorators’ water color paints. In stenciling wood that has been painted, or finished in oil, like Flemish or mission furniture, use oil colors, in tubes, as much oil as possible being absorbed from them as they are employed by squeezing the required amount on blotting paper.

Metallic colors are used for leather in all sorts of rich shades; these are thinned with oil. The problem of stenciling on fabrics is more difficult, since so many pigments with oil or water in their composition have a remarkable tendency to spread over the surface, leaving a ring around the color. Regular water colors thickened, or oil colors thinned with turpentine are usually employed. Though, to be sure, they will not take kindly to the laundry tub.

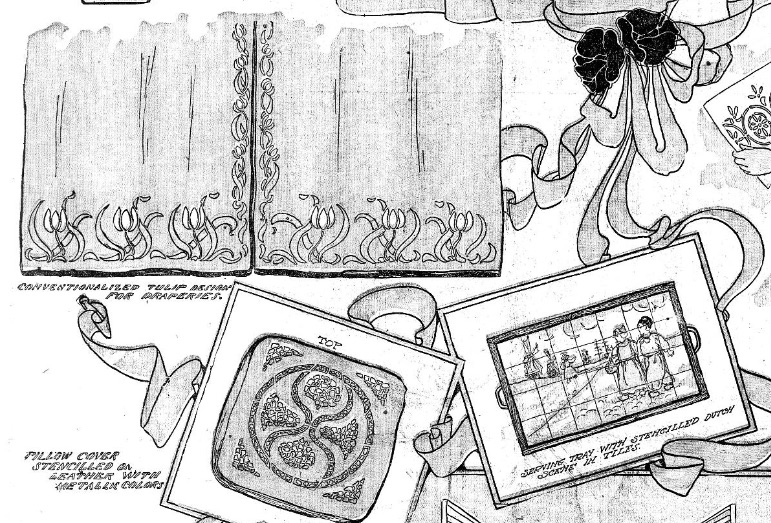

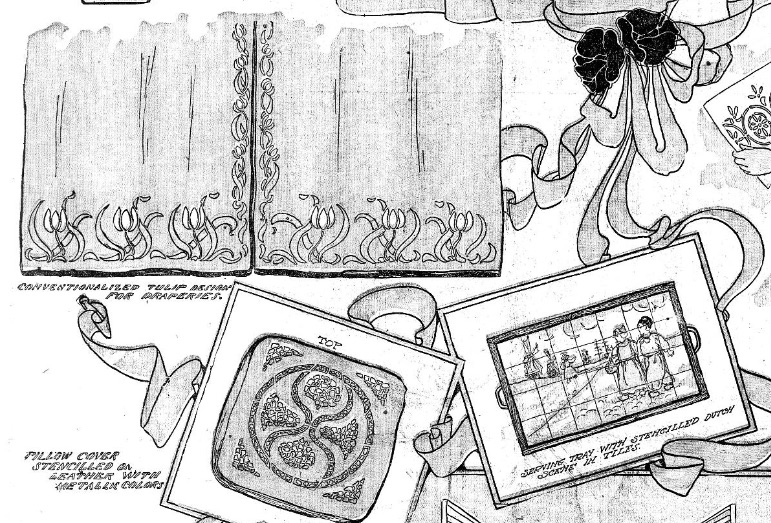

At the top of the page an effective pattern is given of conventionalized tulips to be used for curtains or door way draperies. Material may be of pongee, bobbinet, linen or denim; the color, yellow or green or tan shows up realistically.

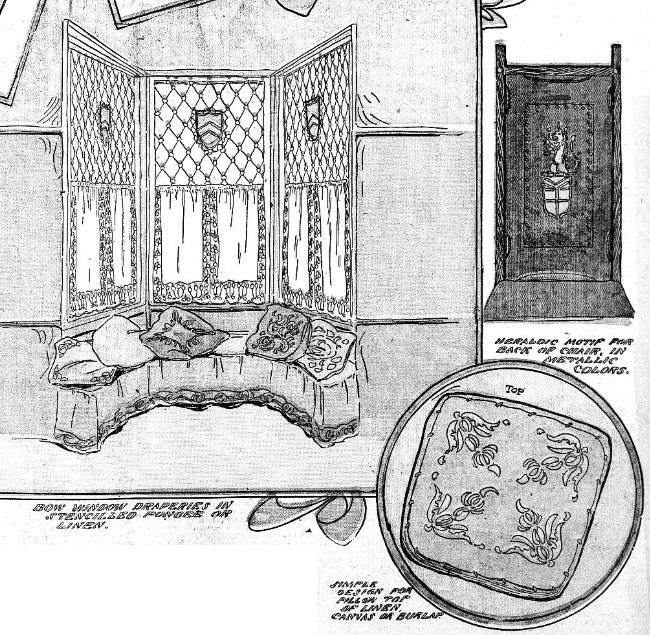

The cushion beneath is of leather, in an odd mosaic pattern put in metallic colors. The serving tray, in blue and white, shows a characteristic Dutch scene; frame of wood. Just above is seen the stencil pattern ready to be applied to the surface. The curtains in the bay window have a border of flowers, bunches of cherries or miniature bunches of oranges. Stencil designs on leather, especially those of the heraldic order, are rich and effective for chair decorations.

Source: The Minneapolis journal. (Minneapolis, Minn.), 11 March 1906.