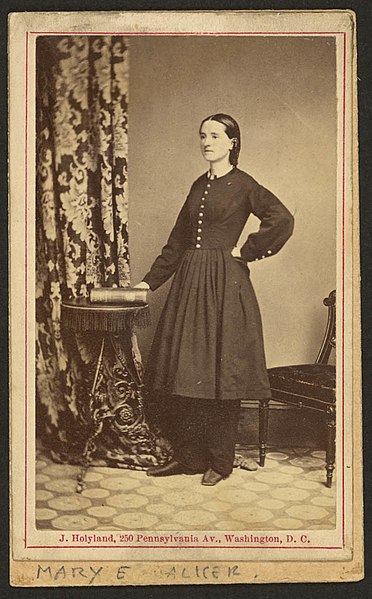

“We live in deeds, not years.” – Dr. Mary E. Walker

Ever since she could remember, Mary Walker had a mind of her own. For one thing, she wore modified men’s trousers under her skirt. It was easier for her to get around in men’s trousers as opposed to taking large strides in the large skirts women had to wear. Although she was a doctor and served fearlessly for the entire Civil War, she was best remembered for being a pioneer feminist in the United States and, of all things, for wearing men’s trousers.

Childhood

Born to abolitionist parents on November 26, 1832 in Oswego, NY, Mary Edwards Walker was taught from a young age to think for herself. She once said, “Before I was sixteen, I saw the inequality of the sexes in the matter of dress. I then decided that at the first opportunity I would adopt the most natural costume that suggested itself.”

Her parents encouraged young Mary to pursue an education, and that is exactly what she did. She attended Syracuse Medical College and in 1855, at the age of 23 she graduated with an M.D.

Marriage

While some newspaper reports from the early 1900s state that Dr. Walker never married, she did in fact marry a fellow physician, Albert Miller, shortly after she graduated with her medical degree. However, while she was serving in the Civil War, her husband obtained a divorce. As the story was told, Dr. Walker left his bed two years before entering into service because he was being unfaithful to her. Three days after her husband got the divorce decree, he married another young woman in the early morning so as to avoid any interference with his marriage plans. At this point, her former husband drifted off into obscurity, while Dr. Walker grew in her own sort of popularity.

Civil War Service

When the Civil War began in 1861, she was among some of the first people to offer her services as a doctor. She was 29-years-old and strong believed that all people deserved freedom. Sadly enough, she was not allowed to officially join the Union Army because she was female.

She was offered a role as a nurse, but she was a medical doctor and did not want to be pegged as a caregiver when she could do so much more. She wanted to prove her skills and provide comfort to both the soldiers and the civilians affected by the war.

At first she volunteered at a temporary military hospital that had been set up in the U.S. Patent Office, but by 1862 she was sent to the battlefields and began working as an assistant surgeon.

By 1863 her medical credentials were accepted by the Army and she was given the title of “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon.” Her rank was similar to that of a first lieutenant, and she spent her time in the battlefields helping wherever she could.

During her service, she wore a modified version of the men’s uniform which consisted of a blue frock coat and pants with gold piping. “When I had on my overcoat, I looked every inch the man, and I am sure I acted it,” she said.

Prisoner of War

Dr. Walker was the first woman in U.S. history to be a prisoner of war. She was captured by the Confederate Army of Tennessee in 1864 while visiting citizen patients outside the Union lines. Held for about 4 months, she was eventually exchanged for a man of equal rank. After she was returned, she remained in service until the end of the war in 1865.

Congressional Medal of Honor

Dr. Mary E. Walker was the first and only woman to have received the Congressional Medal of Honor. It was awarded to her back in 1865, and Dr. Walker could not have been more proud. She wore the medal pinned to her coat and she kept it with her at all times.

After the War

After the war, Dr. Walker ran a private medical practice and did some writing. She was a celebrated hero in both the U.S. and in England, and she continued to wear her pants much to the dismay of many people.

“When I finally adopted masculine garb, a few years later, the amount of advice and comment the matter evoked was astonishing. My first suits consisted of short skirts with trousers under them. The latter were visible below the knees. It would seem a curious costume now, and it astonished people then. I had to listen to some very critical remarks. It was a ‘disgrace,’ ‘a burning shame,’ and ‘horribly immodest.’ I was also told that I was too lazy to wash petticoats.

“I was told that no sensible man would marry me and that I would be hooted in the streets – not once, but often. Eggs were thrown at me, and sticks and stones as well.

“When I finally put on broadcloth trousers it was said that I ‘ought to be shot,’ ‘ought to be hung’ and even that I should be tarred and feathered and ridden on a rail.”

Dress Reform

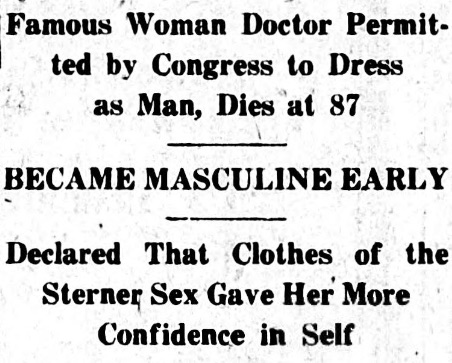

Dr. Walker had been allowed to dress as a man by an act of Congress during the Civil War. After the war was over, she worked towards women’s dress reform. It was obviously a topic that she felt strongly about because she had already been arrested a number of times for wearing men’s clothing.

She was arrested in 1866 in New York for disorderly conduct. A year after she had served in the Civil War, she had dared to appear in the streets dressed in her frock and pants. The police made her pay $300 in bail for her release.

When she was arrested in Chicago for impersonating a man, she had to show the police the documents that granted her the right to dress as a man before they would release her. The only thing she had to say about the arresting officer in Chicago was that, “He’s an old idiot.”

She once said, “This is a free country and as I was not responsible for being a woman, I failed to see the reason why I should be compelled to endure the discomforts of skirts for a lifetime simply because I didn’t happen to be born a man.”

Suffragist

Of course, Dr. Walker fought for women’s rights to political suffrage. However, she felt that women needed to stop acting silly and get serious in order to gain their equal rights. “Women will get suffrage just as soon as they stop making fools of themselves. They’ve got to stop talking so much and do some work,” she said. She wrote and published a book in 1870 titled “Hit: Essays on Women’s Rights.”

Poor Eyesight

After the Civil War, Dr. Walker’s eyesight began to fail. She could no longer work as a surgeon. Since her diminished eyesight was caused by the war, she was granted a pension by the United States Government in 1888. She received a mere $25 a month whereas some of the widows of soldiers received anywhere from $50 to $100 a month.

Withdrew her Medal

In 1917, the government changed the criteria necessary for receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor. The honor bestowed upon Dr. Walker for her work and dedication during the Civil War was taken from her because she was never formally enlisted in the Army.

As a final act of defiance, she refused to return the Medal of Honor and continued to wear it until the day she died because she was proud of her accomplishments.

Financial Distress

By 1918, newspapers reported that Dr. Walker, then 86-years-old, was in financial distress. Her pension for service was not enough to maintain her. Her health was failing and she was in a feeble state. The Grand Army of the Republic was able to provide her with a nurse, but the care was only temporary.

Death

On February 21, 1919, a year after the reports of her failing health, Dr. Mary Walker passed away in her home at the age of 87.

Medal of Honor Restored

After her passing, the people did not forget about the outspoken and brave Dr. Mary Walker. She had not only served in the Civil War, but she had served her patient in the tuberculosis ward she ran. She was a woman dedicated to her work, and one who was fiercely proud of her country.

It was for these reasons that, 58 years after her death, Dr. Mary Walker’s Medal of Honor was restored in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter.