Good luck charms from over a hundred years ago were similar to the charms we have today with one exception: the swastika. Well before Hitler’s party adopted the swastika, it was a popular charm in the United States and was kept by both soldiers during the first Great War and by civilians.

Strange Charms

By Garrett P. Serviss

It was inevitable that the great war should bring many superstitious notions to the front, and especially those relating to lucky charms and guardian mascots, I find the two following, which are new to me in detail though not new in principle, reported from England.

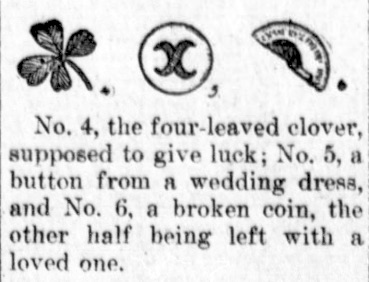

An English soldier took as a mascot a button cut from his mother’s wedding dress. He has been in seventeen severe engagements and many small flights, but has not received a scratch.

An Irish soldier, before starting for the war, pulled with his own hand, in a field near Dublin, a quantity of shamrocks which he carried in a little green bag, suspended from his neck. He firmly believes that this charm has shielded him from all harm in his many desperate fights.

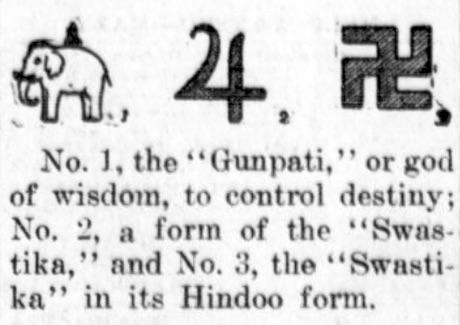

England’s Indian troops have, it is reported, brought many mascots along with them to turn aside German bullets and shrapnel. Among these are some of a very curious nature, for instance, miniature ivory images of a white elephant. This is not regarded as a direct charm against death, but as a representative of the god of wisdom, which will enable its wearer to control destiny. Here we see the subtlety of the Hindu mind, the idea being that the protective power is one that acts through inspiration, teaching the protected person how to escape and avoid danger, instead of simply shielding it off.

The famous swastika occupies a conspicuous place among the mascots brought by the soldiers from the Orient, for, although it is a symbol that has been found in all quarters of the world, it is probably regarded with greater veneration in India than anywhere else. There is some mystery concealed in the history of the swastika. In the old world it has been found carved on tombs in the ruins of Hissarlik, the legendary Troy of Homer’s Iliad; represented in the ancient cemeteries of Etruria; cut on coins of Asia Minor; inscribed on Buddhistic monuments in India, used among religious symbols in Tibet, and worshipped in ancient Scandinavia, while in the new world, at the time when the first Europeans arrived, the swastika was known among the Mexicans, the Central Americans, the Peruvians and other Indian nations and tribes. It has been exhumed from prehistoric graves in the United States.

No universally accepted interpretation of this strange symbol has been offered, notwithstanding all the study that has been devoted to the subject. According to many it was originally a symbol of the sun. Others think it signified the planet Jupiter, but this appears to be based upon the conventional figure used to represent that planet, and the opinion is not a likely one. The shape of the swastika varies somewhat, but it is always characteristic. It bears some resemblance to a Greek cross. Sometimes it is enclosed in a circle, but the usual form is that of a cross with two equal arms, which are bent at a right angle, half way toward each end from the crossing.

That this ancient and almost universal sign of good luck should be one of the most popular in use on the battlefields of “Armageddon” is not a matter for surprise. People who are not superstitious in ordinary circumstances are apt to become so in a threatening emergency, and such symbols as the swastika have the indefinable power that antiquity gives over the imagination.

Recent events call attention to another kind of symbol, whose origin is as obscure as that of some of the mascot signs. This is the Mohammedan crescent. The usual explanation of its origin is that the Turks adopted from the city of Constantinople, which had taken it for a symbol in the days of Philip of Macedonia, because the crescent moon had thwarted, by its increasing light, an attempt of Philip secretly to undermine the walls of the city. A Mohammedan legend says that the Sultan Othman adopted the crescent for his standard because in a dream he had seen the new moon expand until its horns reached from the east to the west.

But Prof. Ridgeway in England has lately advocated a new view, according to which the Mohammedans got the idea of the crescent, not from the new moon, but from the ancient and long continued use in Asia Minor of amulets made by firing two boar’s tusks together at the base. The figure thus produced certainly bears a closer resemblance to a typical crescent, as it is represented on the Turkish flag, than does a new moon. The wide distribution of these amulets, however, suggests that they may have had a common origin in some symbol pertaining to the moon. They are found as far away as New Guinea, while in Africa they are in common use made of lions’ claws instead of boars’ tusks.

Source: Omaha daily bee. (Omaha [Neb.]), 21 April 1915.