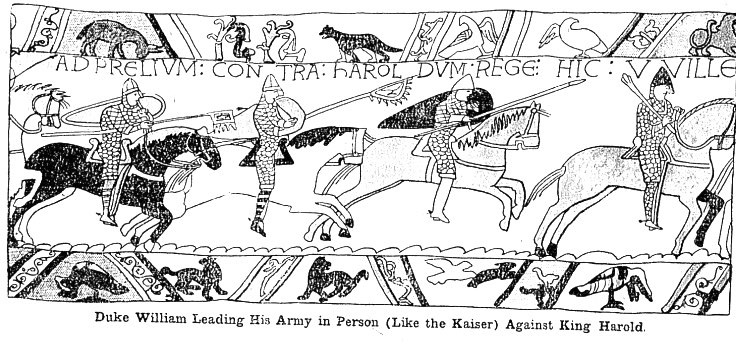

The Bayeux Tapestry gives us about 50 scenes that led to the Norman conquest of England. It is an important work in both the world of art and the world of military history.

The article below was originally published in 1915.

The Oldest Pictures of War in France

Renewed interest has been excited during the present war in the famous Bayeux tapestry that is preserved in the library at Bayeux in Normandy.

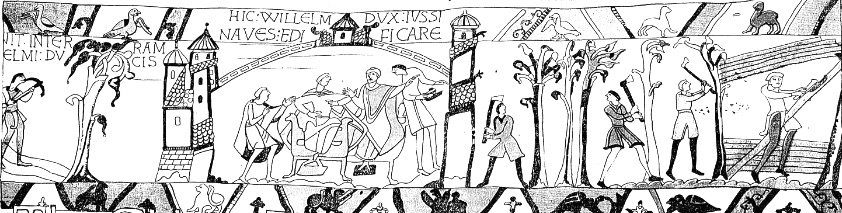

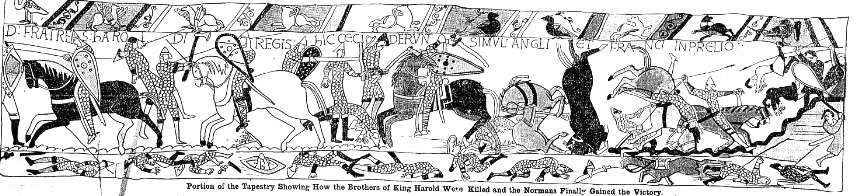

It depicts with wonderful detail every incident in the Norman conquest of England, from the visit of King Harold to the Norman court up to the battle of Hastings in 1066, when William the Conqueror defeated Harold. It was made by Matilda, wife of William, and the ladies of her court.

The tapestry measures 231 feet in length by 20 inches wide.

It is believed to be the oldest representation of warfare in France, and is unrivaled for its representation of ancient costumes, weapons and military methods. At one time the German invaders were within twenty miles of Bayeux, and it is universally believed in France that the Germans would have seized this interesting record of the art in which they consider themselves supreme if they could have put their hands on it.

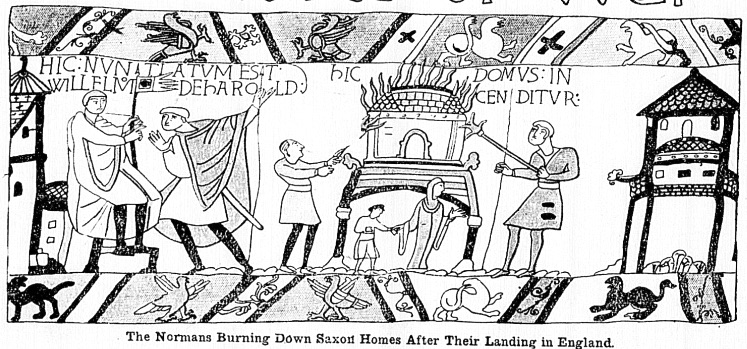

The student of strategy reads readily in these quaint pictorial records that scouting, mass movements, enveloping and outflanking movements were practiced by the Normans and Saxons; that entrenchments were hastily constructed; scouting and observation carried on then very much as now; that villages were burned and looted; that the means of transportation of great fighting forces was conducted in the same fashion as today.

Hilaire Belloc, the distinguished writer on military matters, a historian of no merely bookish mind, who has studied the wars of Europe on the field and on the road, says of these tapestries:

“At Bayeux, in Normandy, a little town as old perhaps as our race and older certainly than our records and our religion, there is to be seen in the main room of what was once the bishop’s palace a document unique in Europe. There is no other example, I think, of a record contemporary, or nearly contemporary, of an event so remote in the history of Christendom, detailed upon so considerable a scale and relating to a matter of such moment. It is these characters combined which give to the Bayeux tapestry its value.

“The Bayeux tapestry represents thoroughly and faithfully one of the half dozen acts essential to the remaking of Europe, an act which, on the analogy of every other of that early time, we should expect to receive from a short and doubtful literary account. It is the one picture we have of any magnitude showing us the things of the Crusading turning point.”

Mr. Belloc goes on to say: “It must clearly be understood in what convention and with what purpose those who made this embroidery worked.

“The object of all this kind of work in every age when it has flourished (and such ages cover nearly the whole of human history) is to establish a record. The motive is ‘lest the deeds of those great men, our fathers, should perish. Now, there are a hundred ways of satisfying that motive, more or less.

“The one that occurs to us today is, of course, inscription. But inscription suffers from two faults. First, it is not universal; secondly, it is jejune.

“It is not universal because the written characters and the language they express cannot be universal. They may be lost or they may become provincial and neglected. It is jejune because full experience is not to be crowding into even an excess of words. What is the alternative? If a record of verbal symbol is so imperfect and if all symbol must be sensual, what other sense can we approach? Humanity has never made anything of the symbolism of music, and never will. It is not fixed. There remain only the eye and the picture meant for the eye,

“Now, in a picture, however rude or however perfect, whether in the flat or the round, you get the most permanent record. All humanity, except our time, has understood that. The appeal to the eye is the most universal, and can be with the least expense of effort the most detailed.

“Our own time will probably suffer more through the neglect of these things, and posterity will ignore us more through our lack of pictorial symbol.

“It does not tell a future age anything to paint a picture of cows at a ford. It tells a future age very little to paint a picture of the Coronation, but to make a bas-relief of one policeman holding up a motorbus, one man selling newspapers to another man, and so on, all along a frieze, would be to give or leave a record of London, and a record which would be independent of the vitality of alphabets and idioms.

“Now, this kind of record demands a convention. In other words, it must be symbolic much more than it is mimetic, and that is the note you get in the work preserved at Bayeux. Not the reproduction of things seen, but the perpetuation of their ideas; a few figures standing for a host; an emblem defining a man; an episode noticed in its simplest terms.”

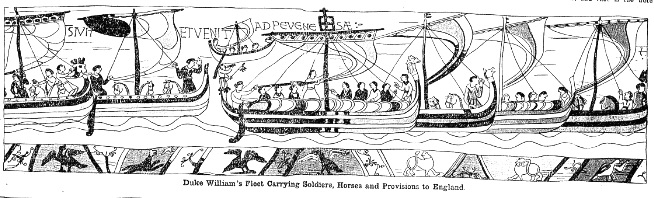

Scores of interesting facts can be learned from these wonderfully realistic drawings by the intelligent student of military affairs. We see, for instance, that William the Conqueror was well supplied with horses in his invasion, although it must have been tremendously difficult to transport them in the small open ships of that age.

The possession of the cavalry was probably an important factor in winning the victory for William, because the Saxon soldiers were entirely without horses.

Source: Richmond times-dispatch. (Richmond, Va.), 24 Jan. 1915.