Visiting the Civil War battlefields around Richmond, Virginia raised a lot of questions about the boys and men who were injured during the Civil War. I visited the local museums and viewed the frightening surgeon kits, but I still had to do the research into what happened to the wounded.

The number of wounded soldiers after each battle was overwhelming. Injured and dying men were collected from the fields and taken to makeshift field hospitals where doctors would rush from one wounded man to the next, quickly deciding who could be saved.

Doctors probed the wounded with their fingers to find out how much internal damage was done. They would then decide who would receive an amputation, who went into surgery, and who simply needed to be stitched and bandaged.

Most bullets during the Civil War were made of soft lead. These soft bullets would expand on impact, creating large entrance and exit wounds. As a result, bones were shattered and tissue was destroyed. There was no way to reverse or lessen the damage, making amputation a necessary evil.

Amputations usually took place within the first 48 hours, and doctors were known to work for up to two days straight, sawing off limbs and removing bullets. During this time, antiseptics were not used and the surgeon’s tools were not disinfected.

Doctors, covered in blood, moved from one patient to the next, without washing, and used the same set of tools on all the patients.

Sponges soaked in blood and pus were simply squeezed out in a bowl of water and reused on the next patient.

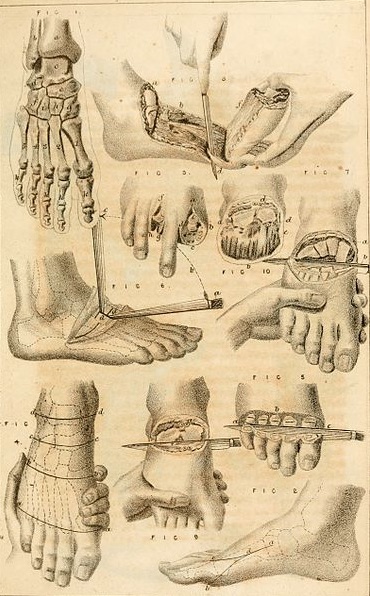

In the best conditions, it took several people to perform the amputation. First, there was the person who administered the chloroform, if it was available. One or more people held up the limb that needed to be cut off. There was also a person whose job it was to close the arteries and prevent the patient from bleeding out. The doctor was the one who cut away the flesh and sawed through the bone with a bonesaw.

A skin flap was left on one side of the arm or leg and the doctor would scrape the edges of the freshly cut bone to remove any sharp edges. This prevented the bone from working its way out through the skin. The flap was then pulled over the stump and sewn shut. A drainage hole would be left open so that the wound could drain out fluids.

After the amputation was complete, the patient was given opiates and whiskey to help with the pain. Again, this was only when these forms of medication were available.

Infection rates were high. Blood poisoning, called “surgical fever,” was common, and entire tents were filled with men suffering from gangrene.

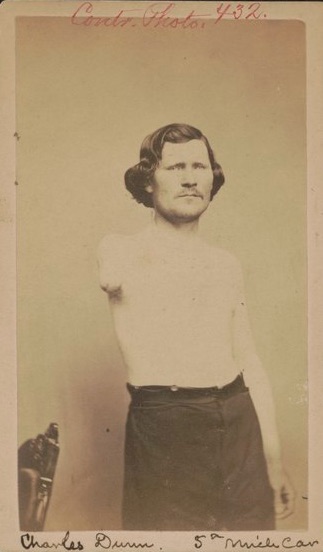

Men who survived all these odds returned home and, after the war, many of them either made their own artificial limbs or bought new limbs so that they could once again return to work.