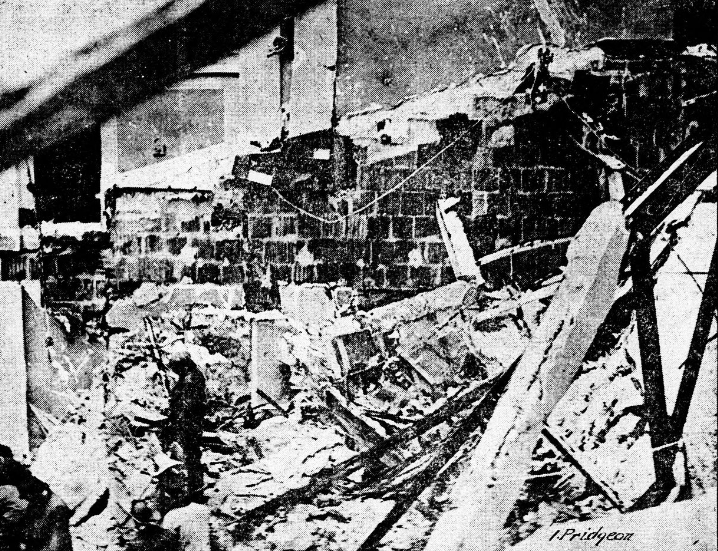

On January 28, 1922, shortly after 9 pm, the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre in Washington, DC collapsed under the heavy weight of snow.

The theater had been filled with people watching the silent comedy movie Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford. As the movie came to its end, the orchestra began to softly play “Sweet and Low.”

And that’s when it happened. A tearing, wrenching sound came from the ceiling and then it collapsed.

98 people were killed. 133 people were injured.

Reporters at Work

As soon as the call for help rang out from box 8-1-7, the city editor immediately sent two reporters to the scene. He knew there had to be big trouble going on and he immediately went into action.

When the reporter stationed at the police headquarters called the editor to relay the event of the theater, the city editor immediately got on the phone and called The Associated Press. Reporters across the country were alerted to the collapse.

The editor’s next step was to rally all of his remaining reporters and get them to key places throughout Washington, DC. The reporters at the scene shouted into the wreckage and gathered the names of the survivors. As each survivor was brought out, a reporter would get his or her first hand account of what exactly happened that night.

Reporters were also stationed at the hospitals and at the makeshift morgue. The names of the deceased were immediately reported so that family or friends could claim the bodies. In the hospitals, the reporters made lists of the injured and their injuries. Deaths were reported as they happened and more first hand accounts were gathered. The reporters did everything in their power to identify any unknowns within the wreckage, and their work was truly amazing.

By the next morning, newspapers across the country reported on the tragedy. For most newspapers, it was first page news as many of the victims were from other states, such as Pennsylvania, Washington state, and Virginia. [1]

A Final Prayer

A morgue was quickly set up a few hundred yards away in the Christian Science Church. The initial rescuers on the site knew that there would be a lot of bodies coming out of the wreckage. The local morgues would not have been able to handle all of them at once.

Inside the wreckage, two Georgetown University students, W. L. Peters and Wilfred Brosseau, began to recite the Lord’s Prayer. Some of the other victims near them joined in. Two women, pinned beside the students, began the prayer, but never finished. They passed away a few moments into the prayer. Other voices died off, as well.

The students then began to work their way out of the wreckage. They were fortunate enough to have not been pinned down like so many of the others. On their crawl out, they rescued two other women and the small group made it out of the wreckage.

Brosseau died shortly afterwards from a wound in his side. He had been pierced by a girder when the roof caved in. [2]

Survivors’ Guilt

Fourteen fire companies responded to the calls for help in rescuing survivors and recovering the bodies of the deceased, but nothing they had done previous to this incident could have prepared them for the heartbreak suffered by the survivors.

As the rescuers searched through the wreckage, they found the body of Guy S. Eldridge. His wife, still conscious, hugged his body tight in her arms. It was time for her to let go, but she pleaded with the rescuers not separate her from her husband. The rescuers managed to pull her away from the man she loved and get her to the hospital.

Scott Montgomery was pinned beneath the rubble, but he was alive. When rescuers reached him, he cried out that they needed to save the women first. He begged them to leave him behind, but the crew managed to get him out from where he was pinned. Two hours later, he passed away at the Walter Reed Hospital. [3]

Scene in the Morgue

The Army also worked the scene of destruction. At the Walter Reed Hospital, forty soldiers showed up to donate their blood to the victims of the theater collapse.

Inside the makeshift morgue, relatives, survivors, and friends walked along the two rows of the dead. One newspaper described the scene:

“Up and down these aisles of the dead walked those whose fears had drawn them here because of some one missing in the family circle. Women already weeping in certainty of what they must find sooner or later beneath the kindly blankets that shielded the sleepers, made the journey of sorrow many times before they found what they sought. Men with working faces leaned to draw back the coverings and then gasp with short lived relief as they moved on to the next huddled form.

“Some of these seekers came with dirt and grime of the wreckage upon them still. Some had passed through the crash of roof and balcony only to leave a dear one dead in the tangled mess. They had worked hours with the rescuers to find that one, only to turn now and then for a hurried trip to the chamber of death.” [4]

Asleep in the Wreckage

There were children in the theater on the night the roof collapsed. Ten hours after the cave in, two little girls, ages four and six, were found sleeping under the wreckage. Neither of the girls were badly hurt, and they were whisked away to the hospital for further observation.

Twelve-year-old Hubert Nash was also in the theater with his 23-year-old sister. When the roof collapsed, they were imprisoned in the wreckage. Hubert’s head was pinned down on his sister’s back and each time he started to fall asleep, his sister would jab him, fearing that he was dying.

In his own words, the boy said, “I was sitting in the first row balcony, and when the roof fell in, it just threw me on my knees, and my head butted into my sister’s back, and that’s the way we stuck for five hours. We were both pretty much frozen, and my legs felt pretty cold. Outside of that, I’m all right.”

Rescuers found them at around 2 am Sunday morning. They had to cut away at the cement and plaster that surrounded them and pull them out of the hole, but both were alive and doing fairly well. They were taken to the hospital for bruises and scrapes. [5]

The Violinist

When Joseph Wade Beal was born, his father had only one dream for him, and that was for Joseph to become a violinist. Joseph began his intense study of the violin at a young age and then, after serving in the Navy, the twenty-two year old became a first violinist at the Knickerbocker Theater. Four days before the ceiling came crashing down, the young man married his boyhood sweetheart.

But that all ended on January 28, 1922. The young man lost his life in the collapse and left behind a young widow. [6]

Served His Country

Twenty-six-year-old William Crocker, a native of New Jersey, served his country during World War One. After giving his service, he became involved in numerous community works and was in Washington, DC as the representative of the World’s Trade Club. He married and five months later he died in the theater collapse.

The couple had been seated together in the third row of the balcony when the ceiling crashed down. His wife heard a low moan and she grasped his hand, but he did not grasp her back. He had died instantly, and his wife remained with him for the next 4 hours, awaiting rescue. It was reported that she suffered from an agonizing mental shock, but had no serious physical injuries. [7]

The Terrible Wait

War veteran Joseph Younger and his wife were at the theater that night. He described his experience as follows:

“Two things saved Mrs. Younger and myself. First, we were sitting in the orchestra near the aisle and when the crash came I shoved my wife into the aisle and fell next to her. Second, the largest girder supporting the balcony, as I remember it, fell just in front of us and shielded us from the mass of concrete and plaster which fell like a giant pancake. Many people must have been killed by that girder which saved us.

“It was five hours before my wife was rescued, and six before they got me out. It was like an eternity. It was maddening. Every now and then in answer to my shouts I’d hear the sound of a pick breaking the plaster shell that covered us. Then a woman would scream and the pick would strike above where she was thought to be lying. And for ages I’d heard no sound.

“That was the worst part of it. Mrs. Younger and I were afraid they’d miss us. We were afraid because we could tell fairly accurately that the woman nearby was dead. She had screamed, then moaned, and then grown still. Others around us in that black mass who were still alive screamed louder than I could shout because I was pinned flat on my back and my wife was, too.” [8]

Screams and Moans

Another survivor, John H. Smithwick of Florida, gave his account of events from a hospital bed. He said:

“The orchestra was playing beautiful music and a comic film was running. Suddenly there was a sharp crack. I looked up and saw a great fissure running across the ceiling. It was right over my head, I instantly realized what was happening. The plaster began to fall, dropping down in large and small chunks all over the theater, it seemed to me. While I was looking up a great piece right over my head started to fall. I ducked, crouching involuntarily, I suppose, down between the seats. The piece struck the seat right where I had been sitting. The force was broken by the seat, but it pinned me down where I was crouching. The noise was awful. It was a great, tremendous roar. It was simply indescribable. I never can forget it.

“In the midst of the roar now were shrieks and cries of women and children and a few shouts of men. There were cries for help, groans and, worst of all, the moans of those in terrible pain. It was awful. I can’t describe it. I see it all the time, those poor children and men and women crying and groaning there.

“There were only a few of us in the balcony. Luckily, there weren’t more. The balcony gave way and crashed, soon after the ceiling began to fall, on those on the lower floor. They were caught the worst. We in the balcony were more fortunate.

“I guess there was a lapse of maybe twenty seconds, hardly more, before the balcony fell. Funny, but it spun around, kind of twisted, as its supports gave way, and it swung down on those below. It didn’t go straight down, just kind of slid sideways and slanting, I suppose from the weight of the debris that had fallen on us upstairs.

“I don’t know how I got out from where I was crouching under that chunk of plaster that had fallen on me. I really believe it weighed all of 500 pounds. And I think I moved that plaster with my shoulders. Anyway, I crawled out between the seats to where I saw a small hole in the plaster above. I forced myself up through that hole, wiggling and shoving. Then I crawled out over the snow and plaster, over the tangled debris, to the doors on the 18th street side.

“Across the aisle from me when the crash came was a little fellow who laughed and roared at every funny part of the film. I don’t know what became of him or the others in the balcony after we were showered with plaster.

“As the ceiling broke the plaster fell first, in chunks. It was just like an ice pond breaking up. The roof didn’t give way on one crash. It seemed to break up everywhere. That let in the snow, which came in through the broken places where the ceiling had given way.

“It’s queer, but I was conscious all the time when I was pinned down under there by that great piece of ceiling. My mind, when I saw the ceiling fall, and afterward, was just as clear and collected as it is now. I knew I was hurt some, but I didn’t know how badly. It seemed that my time had come. I lived a year, I tell you, pinned down between the seats.

“It wasn’t until I got outside that I noticed blood falling from my face and hands. I got out myself. No one helped me. I crawled over the broken seats and plaster and snow to the door. On the way I saw a young fellow lying half curled up, moaning and crying for help. I leaned over to lift him and then everything went black. The next I remember I was at the door, wiping the blood from my eyes and mouth. I don’t know how I got out. I didn’t see any other injured ones as I crawled out. I can’t remember about that part of it. My only thought then was to get home before I should die. My chest pained me, my back seemed broken, my face was dripping with blood. All I wanted to do was to get home and tell my wife and little girl what had happened and how I was hurt. I thought I was going to die.” [9]