The General Slocum was a side wheel passenger steamboat with a hull built out of white oak and yellow pine.

On June 15, 1904, over 1,400 people boarded the General Slocum, most of whom were women and children. They were on a trip that would go up New York City’s East River, across Long Island Sound, to a picnic site called Locust Grove.

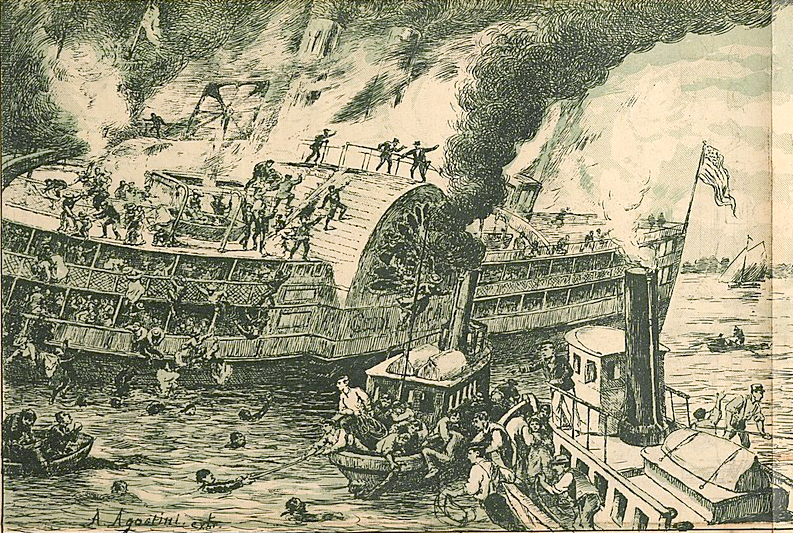

Soon after the steamboat left dock, a fire broke out. There are some discrepancies among survivor accounts as to where the fire began, but ten minutes later, fire was blazing in several sections of the ship and the ship’s captain was notified.

The crew immediately tried to unroll the ship’s fire hoses, but the steamboat’s owners had never replaced the original hoses, and they fell apart from rot. The desperate people tried to use the lifeboats, but found that they were wired and painted in place. Life preservers were also rotted and fell apart.

Flammable paint helped the fire spread across the ship and people began jumping overboard to avoid the fire, but their heavy clothes and their inability to swim brought them to their end.

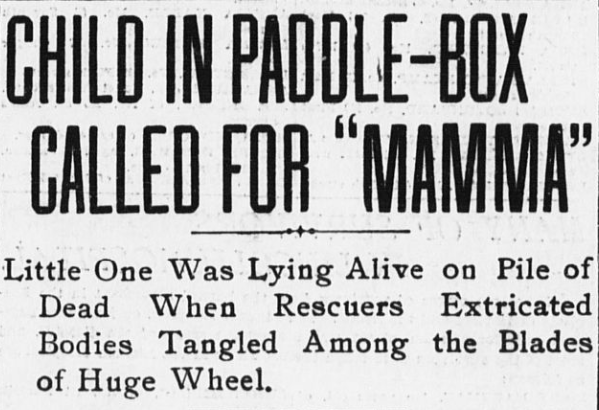

Many people died when the ship’s floors collapsed. Some jumped overboard, only to be battered to death by the side wheel.

The steamboat sank into the East River, and over 1,000 people on board the steamboat had either drowned or burned to death. 321 people survived.

It was New York City’s worst disaster until the September 11, 2001 attacks which claimed nearly 3,000 lives.

In this video, we will take a look at some first hand accounts of the Slocum disaster.

First to the Rescue

Policeman James Collins was one of the first men to reach the burning steamboat. He said:

“I heard the terrible screaming out in the stream. I looked up and saw the Slocum blazing and persons dropping into the water. With Farrell and Jansen, I jumped into the yawl and rowed after the burning ship as fast as possible. Tugboats were then following her, but the heat was so great they could not get near her. When she beached, we pulled toward her, but as we came nearer the heat singed our hair. We threw our coats over our heads and pulled toward the roaring fire. Presently we found ourselves well up under the sides of the ship.

“When I pulled the coat off my head a terrible sight was before me. There, clinging to the paddles of the great wheel, were, it seemed to me, one hundred women and children and a few men. As we came nearer they cried to us frantically to save them. Every second or two one of them would drop into the water and sink. We went alongside, and by keeping away a few feet managed to drag fourteen into the boat.

“‘Hang on,’ we cried, ‘till we come back.’ But when we started to row away others gave up and dropped into the water. We landed our first load on a scow and went back twice more, taking off twenty-two.

“I noticed three large women who seemed to be quieter than the others, and we finally dragged them into the boat and found they were dead, but still clinging to the paddles. Their heads were partly under water.

“Several times we were nearly swamped by women and children grabbing the boat. We had to push back those we could not save. I believe there were more bodies that went to the bottom than were recovered. Most of these will never be found.”

Shortly afterwards, bodies began washing up on shore. Men and women ran to each new body. The living were taken away in ambulances while the dead were gathered up to be identified by family members.

Tugboat Arnott

Captain Van Etten was another brave person who come to the rescue. In his words, he said:

“While bringing the Arnott down the sound and when a short distance east of Rykers Island I saw about a mile ahead a cloud of black smoke blowing from a large steamboat. Ringing for full speed, we soon got to the Slocum. Coming up on the port side, the Arnott stood within a hundred yards of the blazing vessel. One man got out the hose, for the intense heat was already scorching the paint of the Arnott, and two of the crew, John Olsen and Gunder Anderson, peeled off their outer clothing and jumped into the water, which was filled with floating persons, some dead, others unconscious and some begging to be saved. Olsen and Anderson seized and brought to the side of the tugboat eight persons, six women and two children. Three of the women were unconscious. Then the two brave fellows recovered fifteen dead bodies, one being that of a big man who was expensively dressed. A large diamond glistened in the bosom of his shirt.

“Olsen saw three children not more than 6 years of age floating near the shore. Jumping overboard he rescued two. Holding their heads out of the water with his left arm, he used his right in swimming. Then he returned to the other child floating in the water and swam with it to the island.

“Three times the tugboat caught fire. A launch from North Brother Island brought a physician who revived the three unconscious women. One of them became crazed and attempted to commit suicide by jumping overboard. A 9-year-old boy also became temporarily insane. He declared his mother had been drowned, and he fought desperately and attempted to jump overboard.”

Survivor Stories

One of the survivors was Rev. George Haas. He lost his wife and daughter in the river. According to him:

“The fire started in the kitchen, in the forward part, when we were off One Hundred and Thirty-fourth street. I understand that some fat that boiled over started the blaze. At that time most of the women and children were jammed in the rear end of the boat, where the band was playing.

“Why the captain did not point the boat for the Meadows I do not understand. He kept on and the fresh wind drove the fire back on the decks. In three minutes from the time the fire started all the decks were ablaze. I was in the rear of the boat with my wife and daughter. Women were shrieking and clasping their children in their arms. Some others had as many as three or four with them.

“When the fire shot up to the top deck and drove the crowd back the panic was terrible to witness. The women and children clung to the railings, but could not keep their holds. I, with my wife and daughter, was swept along with the rest.

“I believe that the first that fell into the water were crowded overboard. After this there seemed to be a general inclination to jump. The women and children went over the railings like flies.

“In the great crush many women fainted and fell to the deck, to be trampled upon. Little children were knocked down.

“I got my wife and daughter out on the rail and then we went overboard. I was in such an excited state that I do not remember whether we were hurled over or jumped.

“When I struck the water I sank and when I arose there were scores about me trying to keep afloat. One by one, I saw them sink around me. But I was powerless to do anything.

“With a great effort I managed to keep afloat, but my strength was about gone when a man on one of the tugs picked me up.”

Twenty-two year old John Edell was another survivor. He lost his mother and younger brother in the East River. He said:

“When we left the pier the decks were packed to the limit of their capacity. The band was playing, the children were frolicking about and we were having a fine time. As we neared Hell Gate the children were called down to the lower deck, where ice cream and soda water were served. They were literally falling over one another in an effort to get to the tables which held the refreshments. With my mother and my little brother Paul, I went to the engine room to watch the machinery.

“Suddenly there was a burst of flame that rushed up through the engine room and flashed out about us. The flames spread with the rapidity of an explosion, setting fire to the clothing of the women and children who were grouped about the engine room.

“There was the most terrible panic as the burning women and children rushed out among those surrounding the ice-cream and soda water tables. In the terrible scramble my mother and little brother were swept away from me and carried toward the side where the children and women, with their clothes burning, had begun to jump into the water. The flames spread in bursts that soon had the entire deck enveloped.

“The crew was helpless to render any assistance or make efforts to check the advance of the fire. We were just passing out through Hell Gate when the fire started. The captain headed the boat toward North Brother Island and the pilots, who were with him, yelled frantically to us to stay aboard until they beached the boat. But in a moment after the flames had burst from the engine room, great numbers began to jump overboard. The women were wild with fright, and picking up their children, leaped into the whirlpools that carried them toward the rocks on both shores.

“I endeavored for a few minutes to break through the mad crush and get to my mother and little brother, but I was swept into one corner of the boat and held there, unable to move.

“As the boat kept on her way the breeze drove the flames toward the after part of the steamer, where those who in the panic had not jumped overboard were huddled together. It seemed but a few seconds before the flames had swept down upon the children, who were struggling about the ice cream tables, and set their clothing ablaze. They all dashed to the after part of the steamer in a stampede that carried those who were near the rail overboard against their will. At one time it seemed to me as if the women and children were pouring over the sides like a waterfall.

“As we made for the shore the captain blew his whistle in one continuous blast and soon boats of all descriptions were making for us from every side of the river. I was rescued by a launch just as the boat settled close to the shore.

“When she was grounded the flames had spread over the entire upper and lower decks. There was only a few spots on the boat untouched by the flames and in these were piled men and women who had fainted and, falling, pinned others to the deck.

“The men from the tugs who could get near the steamship shouted for those on board to jump and then the small boats picked them up by the score.”

Mrs. H.W. Turner was on the Slocum that fateful day, and she later had something to say about the ship’s life preservers during an inquest the was held about a week after the incident. She said:

“I was on the boat with my mother, my sister, my nephew and my own little girl. My nephew and sister were lost. I was first attracted by several men trying to pull down a hose which broke in their hands. Then I said to my mother that there must be a fire and we tried to save ourselves. I pulled down three life preservers from the ceiling, but all of them broke and were no good. The ground cork poured out. The canvas split whenever I touched it. My mother, sister, and nephew were carried away from me, but I wrapped my arms about my little girl and as the flames came up we were driven to the rail and then crowded overboard into the river. I was unconscious, but still holding to my child when we were picked up and carried ashore.”

Divers and Grappling Irons

Divers worked tirelessly to bring up the dead that were trapped within the remains of the steamboat.

It was reported that:

“All through the night and into the gray dawn of today, men in diving suits, others with grappling hooks in their hands stood on the decks of tugs which hovered about the sunken wreck of the General Slocum off Hunt’s Point. Now and then a man in one of the weird looking suits would slip over the side of a tug and sink to the bottom.

“Then another diver would appear on the surface. Probably he had come to the surface for rest and air. Probably he held the body of a woman or the body of a child in his rubber coated arms. The chances were that he had come up with the dead, for those divers felt no exhaustion as they groped about the bottom of the river among the dead.

“As a diver would bring a body to the surface, a grappling hook was placed under it and it was raised to the deck of a tug. Some of these bodies were twisted and burnt almost beyond recognition. When several bodies were recovered, another tug from which divers were not working would pull alongside and the dead transferred.

“How many dead lie in that charred and sunken hull cannot even be estimated until every nook and corner has been gone over by the divers.”

Grappling irons were also dragged along the bottom of the East River with much success.

One report stated that:

“Six bodies were recovered off North Brother Island by men dragging the shore with grappling irons. Two of the bodies were of young girls, two of boys, and two of men. One man was stout, wore a gray suit and tan shoes and had a handsome gold watch in his vest. The other man was slender and dressed in black.

“Thomas McQuade has been grappling for bodies off North Brother Island, working all night long, and was still at work this afternoon. In all he, himself, recovered thirty-six bodies.”

Identifying the Dead

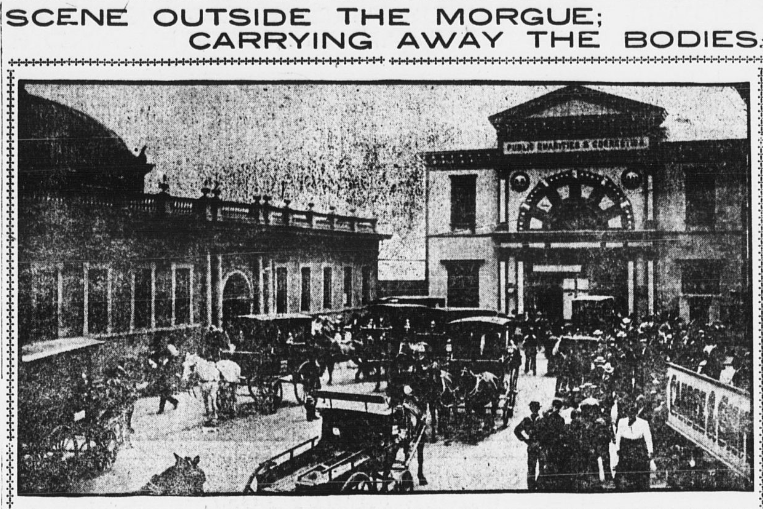

As bodies were pulled from the river and from within the remains of the steamboat, they were tagged with a number and placed in rows for people to identify.

The following comes from a newspaper article published the day after the Slocum disaster. It describes the scene of people trying to identify loved ones:

“The scenes which have marked the finding of their dead by fathers and mother, sisters and brothers, have been such as to shake the nerve of the strongest of the men who are on duty at the pier and most of whom are calloused to such things by years of experience.

“Many do not find those they seek, but they do not go away; they join the end of the long, continuous line and await their turns again, hoping that in the interim the bodies of those they seek arrive.

“With all its heartrending record of sorrowful scenes, the New York morgue has never before in its history been the theatre of such performances as were to be seen there today.

“With its limited space it could not begin to accommodate the silent forms which came knocking at its doors, and long before midnight it had extended its jurisdiction to the long pier of the Charities Department, at the foot of East Twenty-sixth street, along which are now two long lines of plain plank coffins with an aisle between, down and up which the sobbing fathers, mothers and children walk in their ghastly search for their dead.

“In those roughly made coffins are forms, the very sight of which would move a heart of stone. Mothers with their infants so tightly clasped to their breasts that they could hardly be taken away if any one willed such a sacrilege; little girls, their holiday finery bedraggled by the cruel waters of the river and scorched by the flames, some still holding to their breasts their poor little dolls, and one especially, a curly-headed little boy, whose dead hands still firmly hold a little tin horse, the leash string of which now dangles pathetically over the edge of the box which holds him and will hold him until a heart-broken mother or father comes to take him away.”

Insane

There were numerous reports of people becoming insane by grief during the body identification process. It was reported that:

“One woman, Lena Rowski, who found the body of her ten-year-old daughter, Donda, among the dead at the morgue, went insane and was taken to Bellevue, where it is said her condition is considered hopeless. Mrs. Rowski knew nothing of the accident until she visited the morgue and did not know that her daughter had been on board the boat. She became so violent that it was necessary to place her in a strait-jacket.”

Henry Hardincamp had his own difficulties when he found his little eleven-year-old sister among the dead. Upon seeing her in a little pine box, he threw himself across her body and refused to let go. Men had to tear him away from the box and he was eventually forced to leave. The body of his little sister was sent after him to be given a proper burial.

One father, Albert Troell, refused to believe that his thirteen-year-old son was dead. When he and his wife saw his body in the pine box, the father kneeled beside the box and ordered his son to get up. His loud orders disrupted the sobs of other mourners and the police had to gently remove the father from the scene until he could come to terms with his tremendous loss.

Fighting to See the Dead

Those who could not immediately find lost family members among the dead, waited for the boats to come in. These carried the latest underwater findings and bodies that had washed up along the shores.

One report stated that as the boats came to shore:

“…men and women ran forward with loud cries and pleadings. All were sure that the nine would include members of their families who had gone down to death.

“As they fought for a sight of the dead they hoped against hope that their suspicions would not be correct, and yet they fought, and it was not curiosity that prompted them. It was the desire to claim the bodies of those they loved.

“Stretched on the sands like windrows [win-drowz] in a field of harvest were the bodies. They were covered, and those who were not identified were left for a time while those who were recognized were removed by the police.

“Never did day break on such a scene of grief as marked the finding of the dead by the divers on Hunt’s Point.”

Signs of Mourning

The day after the tragedy, the East Side showed heart breaking signs of grief and distress. It was reported that:

“In the narrow confines of a few blocks on the east side there are thousands of aching hearts and weeping eyes.

“Nearly every house in Sixth street have crape tied to the front door. At one tenement, five stories high, five pieces of mourning cloth fluttered, indicating that five families had selected from among the dead their dear ones. And the pity of it all was that on nearly every piece of mourning there was a white ribbon, showing that the dead body was that of a child.

“Women, mothers, stood at their doors waiting for some word of the missing. They had stood there all night. Today their eyes were red and swollen, and as the neighbors passed and asked:

“‘Heard anything yet?’ they answered, ‘Not yet.’ And there was a shake of the head which made their sorrow so sad.”

By the 18th of June, the streets were lined with funeral carriages.

It was said:

“A pitiful feature of the depressing scene was the frequency with which hearses were passed in which more than one coffin was placed. Many carried three little white caskets. A lone carriage following two hearses often marked the passage of a husband and father going to the grave with the bodies of wife and children. Occasionally this father held in his arms an infant left motherless.”