The story of the Halifax Gibbet begins and ends in Halifax, West Yorkshire, England. The little town had its humble beginnings in sheep farming. Eventually, the industrious weavers of Halifax began making an inexpensive woolen cloth that was used for military uniforms.

The fabric was a money maker for the town and merchants from all over England would travel there to purchase it. This, of course, caught the attention of thieves.

Part of the process for making the fabric involved hanging it outdoors. Very little attention was given to guarding the hanging fabric and thieves were known to sneak off with the material.

Thieves who were caught with the goods were immediately beheaded with an axe as a way to prevent future thieves from coming into town and making off with the local people’s livelihood.

The only problem with axing off someone’s head was that no one wanted to be the executioner, and some other method needed to be employed to kill off the offending thieves.

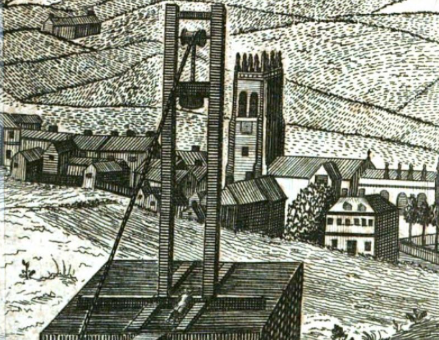

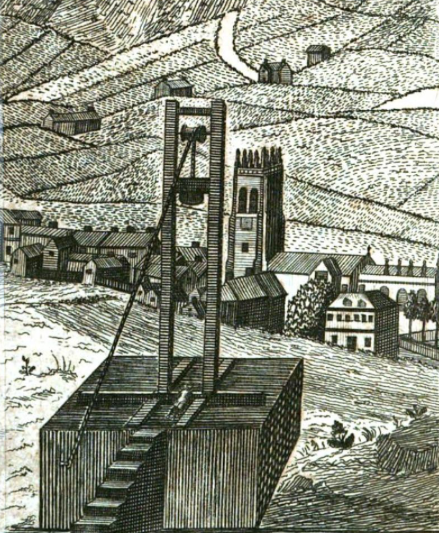

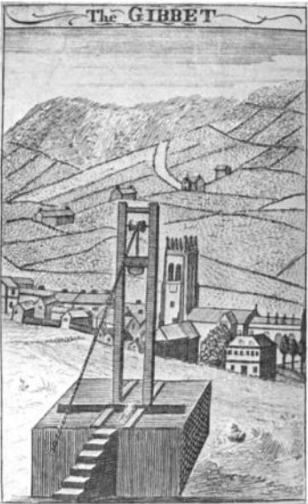

For this reason, the Halifax Gibbet was erected and used from 1541 until 1650. Not only did it replace the axe, it was also considered to be a humane form of execution.

The axe-like blade was never sharpened. Instead, the weight of the large block attached to the top of the blade would drive it down with a force strong enough to decapitate. But since the blade was never sharpened, it generally squashed the condemned person’s neck, removing the head from the body.

Any thief caught stealing items worth more than 13-1/2 pence was placed under the blade.

Before the neck squashing began, the convicted person could be held for up three market days, although sometimes a thief was executed on the same day he was found guilty.

He was usually kept in stocks for public viewing. The items he had stolen were also on display so that everyone would know his crime.

When the time of execution arrived, the condemned was taken to the Halifax Gibbet and forced to kneel. The thief would then place his neck at the base of the gibbet, his neck fitting snuggly into a semi-circular hole.

As soon as his neck was in place, the rope, or pin, holding up the block was released and the weighted blade came down.

You may be wondering why a thief would willingly place his head under the gibbet’s blade, but the answer is simple.

The thief did have a way to escape.

According to law, if the condemned was able to pull his head free of the gibbet blade and run out of the district, there was no legal way to bring the condemned man back. Since the district ended one mile to the south and only a five hundred yards to the north, the temptation to run was ever present.

For example, a man named Dinnis was sentenced to be executed. He was taken to the gibbet where he calmly knelt and placed his head under the blade. As a bagpiper began to play his lament, Dinnis heard the pin being pulled and quickly pulled back his head and started to run north. He made his escape and could not be captured and brought back to the Halifax Gibbet to face his punishment.

Another man, John Lacey, made a similar escape from the gibbet in 1617. However, he erroneously thought that his sentence of death ended after he escaped and, in 1623, he returned to Halifax only to be grabbed and taken immediately to the gibbet where his head was finally lopped off.

The head chopping was never neat and clean, and the head did not land swiftly into a basket.

Instead, there were reports of the head being taken off with such force that it would fly through the air.

There was also a story that a woman was riding past the gibbet as a head was being lopped off. The head went flying through the air and landed in the woman’s lap. She panicked and tried to knock the head out of her lap, but its jaw had clamped down and held tightly onto her apron. It’s said that it took some time to get the jaw unclenched.

The last two people executed on the Halifax Gibbet were Abraham Wilkinson and Anthony Mitchell. The two men were found guilty of having stolen roughly 16 yards of cloth and two horses. They were executed on April 30, 1650

By that time, the public felt that the punishment of death for petty theft was excessive and the gibbet was dismantled. It is unknown exactly how many people met their deaths under the gibbet’s blade, but the names of 52 people have been confirmed as having been executed by the Halifax Gibbet.

The stone platform for the gibbet was rediscovered in the 1840s.

In 1974, a nonworking replica of the Halifax gibbet was built on the site where it can be seen today.

The original Halifax Gibbet blade can also be viewed in the Bankfield Museum in Boothtown, Halifax.