William Calcraft, a 19th century English hangman, was in the hanging trade for 45 years. Originally a cobbler, it is believed that he carried out an incredible 450 executions.

Calcraft began his career in punishment when he took a job at the Newgate Prison, flogging young offenders. In 1829, after England’s hangman, Foxton, passed away, Calcraft was promoted to Executioner of the City of London and Middlesex.

He became a very popular hangman, even though his methods were rather questionable. Namely, he preferred giving the condemned a short drop, about 2 to 3 feet, which, instead of snapping their necks, caused the condemned persons to slowly strangle to death.

His hangings could last up to seven minutes with the condemned struggling and suffering, and there were occasions when Calcraft took it upon himself to pull on the condemned person’s legs or climb onto his shoulders in order to make the neck snap.

Calcraft made a good income in the hanging trade. It was reported that he earned 10 pounds per hanging and that his travel expenses were paid for. He was also paid a pound per month as a retainer. Furthermore, the clothes and shoes worn by the executed were forfeited to Calcraft. He would take these personal items and sell them to the wax museums or he would sell them back to the executed person’s family for a high price. [Source]

One of his most notorious hangings came in 1837 when he hung murderer James Greenacre. Greenacre had murdered his fiancé when he found out that she didn’t own any property. He then “cut the body into pieces and hid portions of it in various parts of London, the trunk being placed under a sack and concealed behind some flagstones…” It was said that on the night before Greenacre’s execution, hundreds of people slept on the steps of the prison and walkways. Boys clung to lampposts all through the night so that they could witness the hanging. The execution brought public fame to Calcraft. [Source]

A hanging in 1856 was an entirely different story and had left the crowd mortified. The London Times reported:

“When the process of pinioning had been completed, [Bonnsfield] let his head drop on his breast, and appeared to have already felt the pang of death. 8 o’clock, the hour appointed for the execution having arrived, the prisoner was raised by four men, and in that manner conveyed to the scaffold. As he appeared totally unable to stand, it was considered best to place him in a chair under the beam – and he was sustained in that position by one of the assistants while Calcraft fixed the rope in its proper position. [A reverend] accompanied the wretched man – but from his apparent state, it appeared useless to perform the usual offices of religion.

“When the signal was given, the chair on which the wretched man was still seated of course gave way with the drop, and consequently the fall was not nearly so great as it is under ordinary circumstances – and at this dreadful moment the prisoner attempted to carry out the desperate struggle for life which he had evidently contemplated. The sound of the falling drop had scarcely passed away when there was a shriek from the crowd of ‘He is up again!’ and, to the horror of everyone, it was found that the prisoner, by a powerful muscular effort, had drawn himself up completely to the level of the drop, that both his feet were resting upon the edge of it, and he was vainly endeavoring to raise his hands to the rope.

“One of the officers immediately rushed upon the scaffold and pushed the wretched man’s feet from their hold, but in an instant, by a violent effort, he threw himself to the other side, and again succeeded in getting both his feet on the edge of the drop. Calcraft, who had left the scaffold, imagining that all was over, was called back – he seized the wretched criminal, but it was with considerable difficulty that he forced him from the scaffold, and he was again suspended.

“The short relief the wretched man had obtained from the pressure of the rope by these desperate efforts had probably enabled him to respire, and to the astonishment and terror of all the spectators, he a third time succeeded in placing his feet upon the platform, and again his hands vainly attempted to reach the fatal cord. Calcraft and two or three other men then again forced the wretched man’s feet from their hold, and his legs were held down until the final struggle was over.” [Source]

Another newspaper report said that Calcraft hung onto the prisoner’s legs for nearly a half hour while the crowd hissed and yelled at him for his incompetence. When it was time to cut down the body, Calcraft “was received with a dreadful storm of shrieks and abuse. He politely bowed to the audience three times and then cut down the body and disappeared.” [Source]

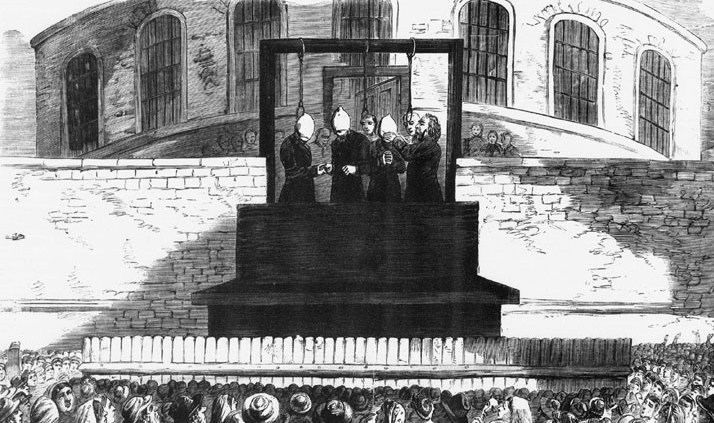

A newspaper article, published in 1867, gives us an account of three Fenian men, Allen, Gould, and Larkin, who were hanged by Calcraft. The article reads:

“Rev. Mr. Keats and Rev. Father Gadd who visited the prisoners last night in their cells, found them all gloomy and melancholy, especially Allen who had previously borne himself well. But in Allen’s case, and in a measure, with the others also, this depression was rather an anxiety to have the thing settled than a fear to meet death; for Allen still expected a reprieve. At half past 11 o’clock the prisoners went to bed, and, let us hope, to sleep. Allen repeatedly said that if he were hanged he should die a martyr to Ireland. Calcraft the hangman, who had arrived at the prison, was almost as gloomy as the victims. He had received a note saying, ‘If you hang any of the gentlemen condemned to death it will be worse for you. You will not survive afterwards…’ So neither the hanged nor the hangman were without a dread of today.

“The prisoners were aroused at 4 o’clock and said that they had passed a comfortable night. At half past 5 they went to mass. [The reverends] were closeted with the condemned until 8 o’clock approached, when Calcraft was summoned and proceeded to pinion his men. Everything was now ready inside the jail, and outside all was quiet. The soldiers were in their places; the crowd was away off behind the barriers and hidden by the fog; a group of special constables stood outside the wall underneath the gallows; the streets of Manchester and Salford, were almost deserted, for the well disposed population had complied with the request of the Mayor’s proclamation and kept within doors; the windows of the houses along Bailey street were full of spectators, in defiance of the police regulations. All was very quiet…

“At 8 o’clock precisely the signal was given, the military were on the alert, and through a line of warders, formed from the prison door to the staircase which led to the scaffold, the solemn procession advanced, the priests chanting the Litany, prisoners responding, ‘Have mercy on us!.’ Allen first came looking very pale, very anxious, very uneasy. [A reverend] escorted him. Larkin came next walking very weakly. He had to be helped up the staircase by one of his jailers. Gould came last, and was in better physical condition than either of the others, He stepped out bravely and uttered his responses in a firm tone. Calcraft and his assistant stood upon the drop awaiting the prisoners. Allen mounted first, and, as Calcraft pulled the white cap over his face and adjusted the rope he shuddered convulsively, and clutched his crucifix nervously. Gould walked straight up to Allen, shook hands with him and kissed him on the right cheek. Larkin felt very ill, tottered to his place with a sickly smile, paid no attention to his comrades and fainted dead away when the rope was applied to his neck. He fell against Gould, but was lifted back to his station by Calcraft’s assistant. They all repeated the prayers after the priests while the caps and nooses were being adjusted, and when poor Larkin’s voice was hushed, Gould’s could be heard saying steadily, ‘Jesus, have mercy upon us.’ A moment and the priests and jailers moved away and the drop fell. Allen died easily; Gould struggled a few minutes; Larkin, aroused from his faint by the fall, was in torture the longest. At 9 o’clock the bodies were cut down and life pronounced extinct. There was no demonstration on the part of the populace except a hoarse murmur of disappointment when the fog shut out the gallows from their view, but some say they heard muttered expressions of sympathy among the crowd. So died the three Fenians who rescued Kelley and Deazy, and tonight all of England is watching fearfully lest in some of their populous towns attempts should be made to avenge them.” [Source]

A year later, in 1868, newspapers gave a detailed report of yet another Irish Fenian hanging. This time, it was a man named Michael Barrett, and it would be England’s last public hanging. One reporter wrote:

“The Fenian convict, Michael Barrett, was hanged this morning in front of Newgate gaol. His demeanor was unaltered to the last, and those who heard his speech from the dock saw another striking illustration of the coolness, resolution, and fortitude he then displayed…. and the ‘Goodbye Barrett,’ ‘God bless you, Barrett,’ yelled from all portions of the crowd, showed that the popular sympathies were roused.

“The proceedings on the drop were unusually brief, and while Calcraft fastened the strap round Barrett’s feet, drew the white cap over his head and face, and adjusted the halter round his neck and to the iron hook chains in the beam above, the pinioned man stood firm and erect, moving obediently to instructions so as to stand in the center of the false floor. Once, Calcraft, with strangely repulsive solicitude, whispered in his ear, as if asking if the halter hurt him, and immediately afterward loosened it somewhat, and the capped head and shrouded face moved dumbly to and fro, as if to aid in readjustment. Calcraft, smiling disagreeably and looking more repulsive than if he had worn the insignia of his dreadful office, smirked and [pulled] the fatal bolt. He had been greeted by a terrific storm of hisses and yells while in view of the people, and seemed nervously anxious to hurry out of their sight… Barrett’s powerful will and enormous self control seemed prominent even in the death agony… Calcraft [placed] his hands on the dying man’s feet as if to steady the swinging body; but without employing the pull or jerk with which he is said to occasionally supplement the dreadful fall.” [Source]

After the hanging, the people began to shout, “Let’s put him there instead!” “Shame!” and “Down with him!” The crowd “hated the hangman more than his victim.”

With public hangings out of favor, Calcraft began plying his trade inside the prisons and away from the public eye.

He also continued his original penal occupation of whipping prisoners. In 1870, there was a brutal account of a whipping performed by Calcraft. The prisoner was twenty-two-year-old William Terry who was convicted for attempting to strangle a woman with his bare hands. The court had ordered that he receive twenty-five lashes with the cat-o’-nine tails and seven years of penal servitude.

On the day he was to be whipped, Terry was taken to the flogging room where the press, Governor, and magistrates waited to witness the event.

A reporter at the event wrote:

“Calcraft approaches him… The executioner goes to work without saying a word. He seizes Terry by the shoulders and pushes him toward the machine. The [prisoner] starts back in terror, but each of the jailers seize one of his arms, and drag him a few steps forward.

“[T]he wooden instrument consisted of a sort of drum and a post with two horizontal arms.

“The drum is divided into two equal parts, one of which, the front one, is movable, and can be raised and lowered, while the other is fixed. As the top of the drum is pierced in the middle by two circular holes, the drum, upon being opened, divides these holes into “half moons.” Calcraft hurriedly pushes Terry into these half moons so as to completely encase the legs of the convict in them. He then closes the drum so that the prisoner’s legs are fastened in the holes completely…

“The ankles are likewise fastened in a lower bottom, which contains also two holes.

“Terry tries to disengage his legs and wants to make a movement, but he feels that his limbs are fastened, as it were, in a vice. He utters a howl and struggles frantically, trying to push back with his hands the jailers and the executioners. The drum is surmounted by a post, which at the height of the shoulders contains two horizontal arms pierced with two holes that are destined to hold the wrists of the criminal as in a vice. Terry, notwithstanding his desperate efforts, soon is utterly unable to move his legs and arms, and his back is now ready for the flogging.

“Calcraft takes from the hands of one of the jailers the terrible cat-o’-nine tails with its many knots, and waits.

“The magistrates consult one another with their eyes, and one of them, making a sign with his hand, says, ‘Begin!’

“The executioner puts forward his left foot, throws his body back, and almost at the same moment the whip falls vertically down on the back of the victim.

“A dull, prolonged cry, in which betrays itself as much impotent rage as pain, issues from the [prisoner’s] breast. His cry has not yet died away on his lips when a second stroke enters the same place as the first.

“A shudder causes Terry’s forehead, as it were, to undulate; he utters a roar, like a wild beast, and commences shaking the machine frantically. The cat whistles again through the air, and seems to bury itself in the victim’s flesh. A single bloody stripe appears on the lower part of Terry’s back.

“Until then the intense pain had wrested from the bandit only inarticulate sounds, but at the fourth stroke it vented itself in panting phrases.

“‘O God! O God! Strike me on the shoulders!’ cried Terry, struggling violently, and foaming at the mouth.

“Calcraft pays no attention to his supplications, and his whip falls with more force than ever upon the lower part of the back of the wretched man. For a moment it seems as though Terry will really succeed in breaking the machine that holds him.

“This torture wrests such terrible cries from the victim that the surgeon makes a sign. Calcraft draws two steps back. The doctor approaches Terry, whose eyes seem ready to burst from his head, and who trembles all over violently; he felt his pulse, and then turns to the executioner, saying: ‘There is not the slightest danger, go on!’

“Calcraft goes again to work. The repose of a few seconds has restored to his arm its strength and vigor. The cat whistled through the air and falls down on Terry’s back. Now several bloody stripes appear on the lower part of his back. Every kiss of the instrument of torture tears out a shred of flesh.

“Terry presents a horrible spectacle. His face is dreadfully contracted; foam covers his lips, and his eyes are bloodshot; he almost lacerates his wrists and ankles in making desperate efforts to disengage his limbs. Now he throws his head back, uttering unearthly yells and shrieks; now he bruises his head in striking it against the wooden post, and now he bites his teeth into his arm!

“Calcraft, on his part, is always calm and grave; his arm rises and falls with the regularity of a clock.

“At the twentieth stroke of despair. His sufferings vent themselves in howls, such as few beings will utter. His skin is torn at every stroke like paper too much saturated with water. The thongs of the cat stick together, and Calcraft is obliged from time to time to pass them through his fingers in order to remove the clots of blood from them.

“At the twenty-fifth stroke Terry feels nothing or almost nothing more.

“Calcraft, who seems to have taken pleasure in this task, raises his hand again, when the magistrate calls out to him, ‘stop!’

“Terry is drawn out of the machine; he falls like a corpse into the hands of the jailers, who hurriedly remove him to the hospital.

“The machine is enclosed again; Calcraft gives back to the authorities the cat-o’-nine-tails, and human justice is satisfied.” [Source]

Newspapers from the 1800s are filled with stories of Calcraft hangings and the punishments he delivered to various prisoners. His name was known throughout the U.K., Australia, and the United States. He fascinated and mortified people, and numerous rumors circulated about who he really was before he became the Queen’s Executioner.