Did doctors use real skeletons long ago and how did they get those human skeletons? It turns out that the wired skeletons that hung from a pole were made in various major cities around the world, including New York City, London, and Paris.

According to the article below, originally published in the late 1800s, the human skeletons were often the remains of people left unclaimed in the morgues. Travelers would also gather “unusual specimens” of people from other countries to be shipped to the skeleton factories, de-fleshed, and made into a lovely skeleton for display.

A Skeleton Factory

A skeleton factory has been discovered in London. From it are procured the majority of the skeletons owned by doctors, anatomical museums, etc. It has existed for some time, but never before has the public been made aware of the fact. Its story is told here for the first time, and the facts presented explain in large measure what has heretofore been one of the mysteries.

Never was Masonic secret more carefully guarded than this one which included the location and methods of this skeleton factory. It is certain that many of the medical men, in fact the greater proportion, who are customers of the skeleton factory, are in absolute ignorance of its existence. They know that certain persons can supply them with skeletons all wired and ready for use. They are wise enough to ask no question, for if the story that lies behind every skeleton were told, many a tale of savagery and of wanton desecration would be revealed that it is better should be kept secret.

At the English hospitals, dissection is not allowed, so all unclaimed bodies are, after the lapse of a certain time, transferred to the medical schools, where, in the dissecting pavilions, they become “subjects,” and the students are taught the science of anatomy by means of these realistic object lessons. The medical schools have no means of utilizing the bones of the subjects and so, when the operation of dissecting is complete, the subject is turned over to the representatives of the skeleton factory and promptly shipped by them to the place where the skull and crossbones are truly emblematic of the institution’s character.

The factory, which was visited by the writer, who therefore tells only that which he saw and has learned authoritatively, is conducted on as strict a system as the most punctilious business house in the United Kingdom. Never was the old adage, “a place for everything and everything in its place,” more strikingly exemplified. Every bone of the human body has its particular place, but when I had completed my inspection the fact was forced upon me that hardly a single skeleton among the countless ones that we see from time to time, is composed of the bones which nature originally placed together.

In addition to the bodies that are sent to the factory from the dissecting school, I learned that travelers often have the curious desire to secure what they know are genuine skeletons of inhabitants of far-away countries. Therefore, they obtain bodies of such persons, and after having them embalmed, send them to London agents of the skeleton factory, who at once see to it that the desire of the shipper is carried out. Many such skeletons are to be seen today in the anthropological museums in different parts of the world.

It takes twelve months to put the human bones in proper condition for wiring. The first step, after the subject reaches the factory, is to cleanse the bones of the flesh. The subjects are therefore placed in tanks filled with water and phonic acid. The next process is that of boiling in strong soda water, after which the subject is consigned to a tank. When the bones have been thoroughly cleansed they are turned over to skilled anatomists who wire them together so strongly that each is sure to retain its proper place.

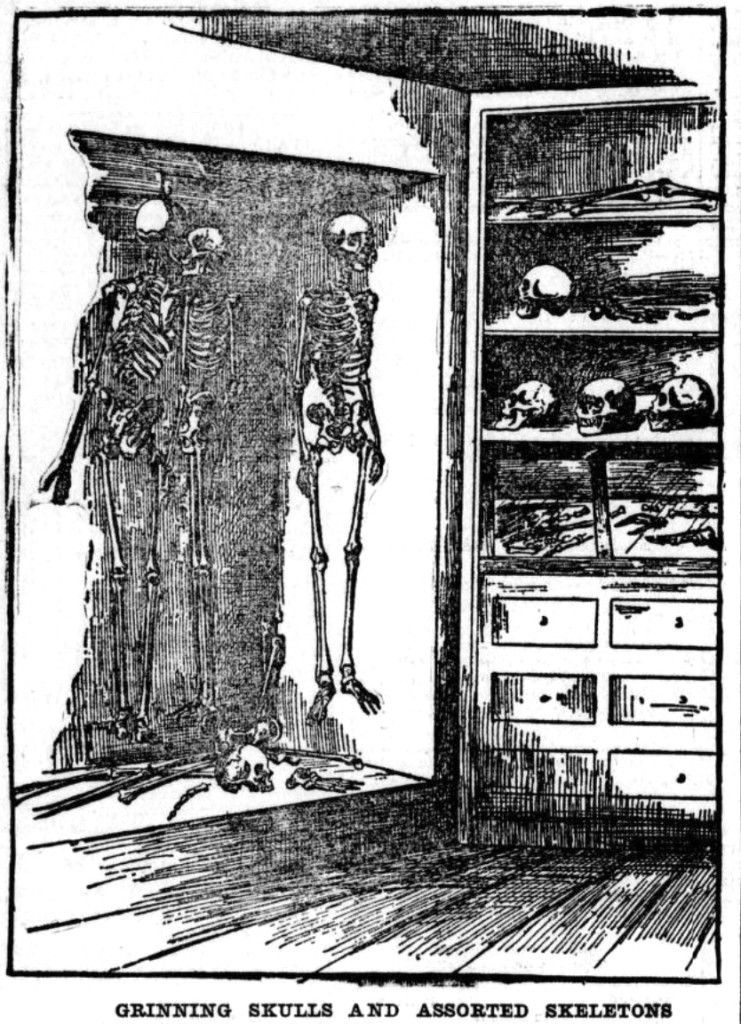

It is not always the case that bones are wired together by the anatomists as soon as they are in proper condition. A visit I paid to the stock rooms of the factory indicated that. There were shelves upon shelves on which were arranged with gruesome regularity skulls that seemed to represent every type of humanity that has ever existed. Some of them had been, for one reason or another, broken into pieces and were held in proper semblance by fine brass wires.

Beneath these shelves ranging upward from the floor to a height of about four feet were huge drawers filled with bones of every description, although they were not fixed together, but the different sorts scrupulously kept by themselves. There were vast heaps of ribs and thigh bones. Every one of the bones in these drawers was lettered and numbered, so that when the anatomist desired to wire a skeleton they would simply write out an order for exactly what they wanted, by number and letter, and the component parts of the skeletons were soon brought to them by one of the workmen.

Not the least important feature of the skeleton factory is the task of the workmen who make it possible for the anatomists to wire the bones together. It may easily be understood that in every bone there must be bored a hole at each end of sufficient size to permit the passage through of a wire. This is a very delicate task, for the bones split easily and, ordinarily, when once split they are useless.

In the workrooms where the more delicate portion of the task of placing the skeletons together is performed, the sight is so odd that one really forgets its gruesomeness. Here an anatomist is engaged in putting together the various bones which go to make up the hand.

Another is putting the finishing touch on the bones of the foot, just as the shoemaker carefully examines the shoe before he turns it over to his assistant to be made presentable. When the task of the anatomist is completed, the skeleton is taken into an adjoining apartment and mounted on a stand attached to an iron rod or the ring which is inserted into the skull is placed upon a hook at the end of a rope which comes down from the ceiling and hangs suspended.

The showroom of the factory indicated perhaps better than all else the exceedingly business-like methods of the establishment. It is very large and light and lined with glass cases containing specimen skeletons of giants, dwarfs, and strange races discovered by travelers in foreign lands. Then there are skeletons of criminals with the name, date of execution and a record of their crimes on attached labels; skeletons of males and females of all ages; shelves of baby skeletons, huge of head and small of body, and others of all sorts.

It was a strange place, and the strangest of all things to me was the absolute nonchalance of everybody about. They appeared to consider the skeleton business nothing more out of the ordinary than the selling of dry goods or the manufacture of toys. I do not believe that one of the persons in this place over which, it seemed to me, the shadow of death and the funeral pall always hung, had any of the physical fear of the discarded mortal tenement that exists in the heart of almost everyone.

I learned in the course of investigating that matter that the London skeleton factory is an offshoot of a parent establishment in Paris which has existed for nearly a century. I also learned that a similar institution was in full operation in New York, and that both places were as busy as they could possibly be filling the orders. This is perhaps accounted for by the statement to me by well posted men that ten thousand skeletons a year are needed to supply the demand. Personally, I think this is an exaggeration, but the demand is certainly very great.

The Parisian factory is under government supervision, but its secret is well guarded, and a few persons know of its existence outside the pale of those who have daily business connection therewith. The factory in New York is located on the East Side . It is said to employ nearly a hundred persons. One of the most curious things about these establishments is the fact that all about them is kept secret so well. One would think in employing so many persons the facts would leak out, but they do not seem to.

Certainly the skeleton factory is one of the most curious of modern institutions. I would not recommend it, however, to any one who is inclined to be nervous.

Source: The herald. (Los Angeles [Calif.]), 18 July 1897.