Here is yet another article about the skeleton industry in the late 1800s. The article has a humor not present in previous articles on this subject. The writer refers to one skeleton as a “ventilated gentleman,” something I simply must remember if I ever chance upon a skeleton display.

The article also explains how the bones were de-fleshed and prepared for display.

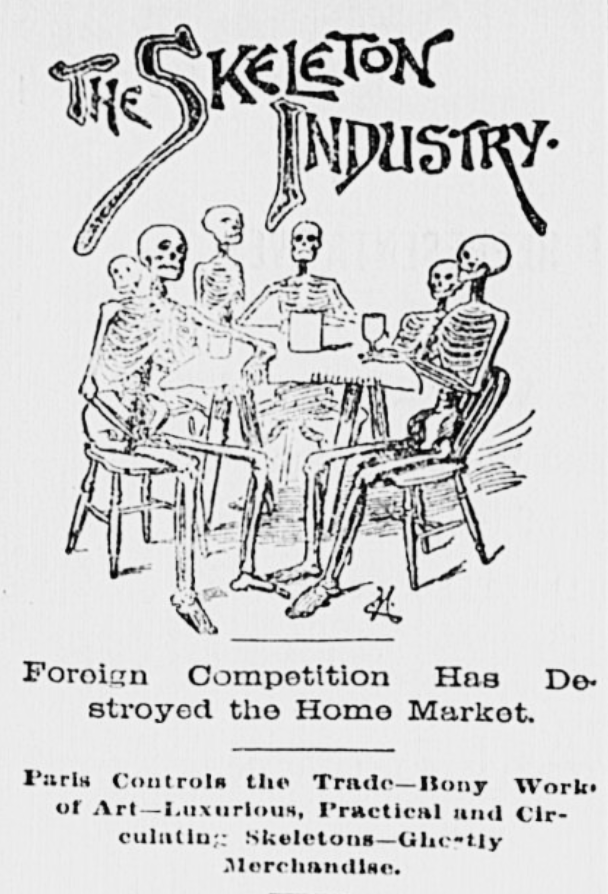

The Skeleton Industry

“Once upon a time” is decidedly “not in it” in this last decade of the nineteenth century. Bluebeard and his paltry assortment of bones would scarcely attract passing attention in a dime museum. The skeleton of today relegates to the shades its osseous predecessor of story and of song. In point of artistic finish and general makeup the world has never known its equal.

Within gunshot of the Fifth Avenue hotel there is a closet which contains a skeleton. No, a dozen of them, that are regarded as objects of beauty by those who know how to appreciate them. Not everyone does.

This grim assemblage represents a company of defunct Frenchmen. Each bears the stamp – not of its maker, nor yet of its original possessor – but of its articulator. It is a guarantee of its genuineness and durability.

Only a medical student, a professional articulator or a grave digger enjoys to the fullest extent a peep into this gruesome retreat. One of the ventilated gentlemen is seemingly minus legs. The custodian explains that they are only temporarily detached and points them out snugly resting in a corner. He was too tall to admit of a full length pose and a sitting posture is evidently not deemed elegant for a skeleton. Another has been obliged to sacrifice his head to space. It is behind him on the shelf. A figure carefully enveloped in brown paper has the appearance of trying to hide his bones. In reality he is a very costly specimen and is carefully guarded from exposure.

The choice collection is for sale, individually or en masse, and unlike the solitary but omnipresent “skeleton in the closet,” they will find ready purchasers, although they are really expensive luxuries, owing to the tariff.

To protect the home skeleton industry against foreign competition an import tax of from 35 to 50 percent has been imposed. Despite this fact domestic skeletons are not in demand, and the regular dealers do not carry them in stock.

French skeletons are the finest in the market and Paris is the head center of the trade.

It is not that a Frenchman’s bones are of such superior quality. It is the other Frenchman that puts them in shape that gives them their great value.

The mode of preparation is a very delicate operation. The scalpel is first called into requisition to remove the muscular tissues. Its work being done the bones are boiled, being carefully watched meanwhile that they may not be overdone. After this cannibalistic procedure they are bleached in the sun. Even then spots of grease are sure to appear when they are exposed to heat. The French treat these with ether and benzine, securing thereby a dazzling whiteness, which is a distinguishing mark of their skeletons. They are warranted never to turn yellow and to stand the test of any climate. New York in midsummer is not too hot for them.

They are put together by a master hand. A brass rod with all the proper curvatures supports the spinal column. Delicate brass wires hold the ribs in place. Hinges of the most perfect workmanship give to the joints a graceful and lifelike movement. Cleverly concealed hooks and eyes render disjunction at pleasure possible. The whole construction plainly indicates the care and skill of an artist and a connoisseur.

Domestic skeletons are generally the work of amateurs. Janitors in medical colleges rescue bones from the dissecting rooms and cure and articulate them. They find purchasers among the students, who on the completion of their studies resell the skeleton, if happily the market is not glutted. A second hand skeleton may thus be had at quite a reasonable figure – occasionally as low as $15.

The imported article, however, ranges from $50 to $400. The very high priced ones are valued because of the preservation of the nervous and circulatory systems. Of course they are beyond the reach of modest purses, and as a taste for medical and scientific research has not yet developed among the millionaires, very few $400 skeletons are sold. They are always a special order.

A very fine French skeleton may be had for $150, and that is about as high as the general run of purchasers care to go.

Skulls, hands, and feet may be purchased separately, but to obtain a rib, an arm or a collar bone the whole affair must be bought.

A skull and crossbones, suitable for decorative purposes, costs by $10. The skull has but one cut, and although it may be very pretty, it is not artistic.

For $22 a skull that will unhinge and reveal its hidden contents is possible. The bones of the ear are comprised in this treasure.

The happy mortal who can put up $75 may become the possessor of a cranium that leaves nothing to be desired in point of minute articulation. He has but to press a button – the skull will at once resolve itself into an anatomical collection. Each component part will quiver with nervous energy on the end of a spiral wire, emanating from a brass upright rod. Only the daintiest fingers could handle with impunity such an exquisite specimen. It has the protection of a glass case.

Ladies who feel that they are never accepted at their proper value in life may console themselves with the knowledge that the skeleton of a woman brings a higher price than that of a man. If they wish their friends to know their worth they have but to bequeath their bones to an anatomist. By the time they are placed on the market their true value will be satisfactorily determined.

There are sometimes very peculiar conditions which influence the price of dead men’s bones. A case recently decided in court affords an example.

A man who was suffering from an ailment which required surgical treatment was so overwhelmed with gratitude for the relief obtained that he drew up a will bequeathing his body after death to the surgeon who had rescued him from agonizing pain. He was a poor man at the time of his illness, but with the return of health fortune smiled upon him and when death and the doctor claimed him he was a millionaire.

His heirs, although cheerfully conceding the claim of the dread destroyer, stoutly protested against that of the doctor. The courts decided in favor of the legatee. The relatives buried the bones of the testator, but the price was high.

The skeleton market is supplied mostly from the pauper and the criminal classes. Patients who die in hospitals and whose mortal remains are not claimed by friends, are passed over to the dissecting room. If their bones escape destruction there they are placed together and further serve the cause of science as skeletons. Sad to relate, the articulator sometimes mixes bones, and the completed anatomical study is quite liable to be half saint and half sinner; a sort of Jekyll and Hyde skeleton.

These specimens are often placed on exhibition as the osseous remains of some celebrated criminal. The public is warned against being horrified by them. The brutal murderer, whose alleged bony structure confronts one and causes a thrill to creep over comfortably covered bones, may, in point of fact, be a mild and innocent composite pauper.

The imported skeletons are guaranteed to be all one person. The manufacturers are disposed to be reticent as to the source of their supply, but they aver that they spare neither trouble nor expense to secure desirable subjects. The “little ladies” of Paris, whose lives so quickly descend the graduated scale, would deem it a not unhappy chance to secure advance payment for their bones. Their volatile temperaments would lead them to regard the transaction as a jovial affair. In point of fact, they feel a certain degree of satisfaction in knowing just what is to become of them, and that they alone will reap the pecuniary benefit.

Imported skeletons are, as a rule, sold to medical colleges and other educational institutions. The College of Physicians and Surgeons has a fine collection. They have also a circulating anatomical library. A large number of skeletons have been divided into sections. These sections are put into nice mahogany cases and are numbered. Students desiring to study any particular bone or section of bone consult the catalogue and draw the case containing the desired object lesson. Two weeks is the limit of time that the case may be retained.

It is quite safe to surmise that the majority of skeletons are filling a worthier role in their disembodied state than they ever did in the drama, or, it may be, the tragedy, of life. An articulated skull that is valued at $75, more than likely, when accompanied by the brain that nature bestowed upon it, was not worth a cent. The glass case not infrequently supersedes prison bars. Altogether, it is a cheerful thought that at least the skeleton is of some use in the world.

It is, however, quite probable that within most of the deserted chambers aching hearts have throbbed and weary brains have struggled. Pathos and sorrow have alternated with joy and gladness. Bright eyes may have gleamed in the unsightly sockets. Tears have surely flowed from them. Like the dead whose bones are permitted to crumble to dust; like the living who regard them with interest or with honor, their life stories are chapters of sunshine and shadow, pleasure and pain.

Source: The Roanoke times. (Roanoke, Va.), 21 Dec. 1892.