The article below gives us a fascinating look at the morgue master in Washington DC in the early 1900s. The description of the “new” morgue and the morgue master’s character are detailed and intriguing. I can almost hear the clip-clap of the death wagon.

Morgue Ranks High

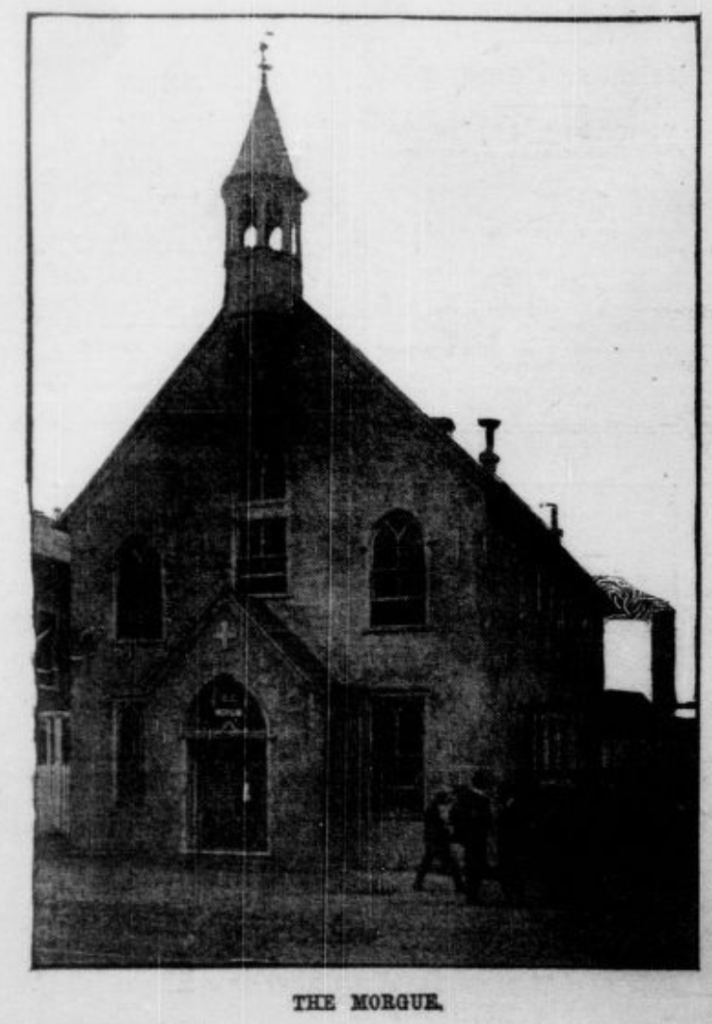

Unknown or unclaimed bodies, as well as, in general, the remains of the victims of homicide and those who die by accident or commit suicide, receive unusually considerable treatment when they reach the District morgue, which is situated at the foot of 7th street, on the river front.

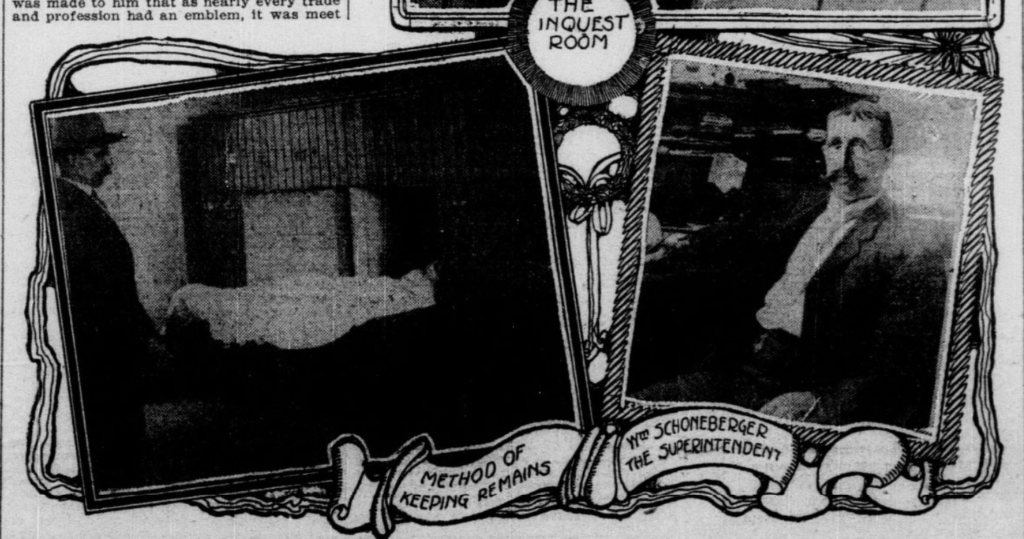

This institution has been visited by several coroners of other cities, who have pronounce it to be one of the best morgues in the country. They have also been liberal in their words of approbation concerning the morgue master, Wm. Schoneberger, who has handled many of the dead of this city for several years. His services in this connection antedate by a long time the establishment of the morgue.

Mr. Schoneberger is known as “the father of the District morgue,” for it was largely through his efforts that it became an accomplished fact. Not many years ago the District was without proper morgue facilities. The bodies of persons dying by accident, homicide, suicide and from other causes were removed from the scene of the fatalities to the stables in the rear of the several station houses. This resulted in so many complaints from those living in the vicinity of the police stations owing to the odors that pervaded the neighborhood that the District Commissioners were compelled to take some action to relieve the unpleasant conditions. So a number of years before the establishment of the present morgue a small apartment in the rear of No. 6 police station, on New Jersey Avenue, was designated as the city morgue.

Former Quarters Cramped

This place was entirely too small for the purposes for which it was used, and the result was that on several occasions of great calamities a terrible sight was presented in the little inclosure. This was notably the case at the time of the Ford Theater disaster when human bodies were literally piled up upon each other in the small morgue room like cord wood, as the late Lieut. John Kelly expressed it at the time. In addition to the smallness of the space, there were no facilities for preventing the odors from the morgue permeating the neighborhood, and the residents of that locality made frequent protests to the Commissioners against the continuance of a dead house there.

Morgue master Schoneberger, with the assistance of the police reporters of the several local newspapers, called attention through the press to the terrible conditions until at last the matter was taken up by the District authorities in earnest, and an appropriation secured from Congress for the erection of the present up-to-date morgue building.

This structure was first occupied in July, 1904. It has ten vaults or cases in which the remains of the dead are kept on ice until disposed of by action of the coroner’s jury, by direction of Dr. J. Ramsey Nevitt, the coroner, or “according to law,” which means that the unclaimed dead, after being retained a certain period, are turned over to medical colleges of the District for scientific purposes.

Double the Capacity

While there are but ten vaults or cases in which bodies are kept at the morgue, the institution in an emergency can, it is said, accommodate double that number of corpses. The slabs on which the bodies are kept are made of wood, and the ice which preserves the remains is kept above this slab and does not come in contact with the remains, each little vault being a sort of cold storage chamber. In the room are wardrobes in which are hung the clothing of the dead. Those wardrobes are ventilated top and bottom. The apartment used for the retention of the human remains is situated immediately adjoining the morgue wharf and above the river. Adjoining it is the inquest room, in which the coroner’s juries hold inquests in cases of homicides and those of certain accidental deaths.

In the front part of the building on the first floor is the office, which is occupied jointly by Coroner Nevitt and Morgue master Schoneberger. Just inside the main entrance door is a small prison cell heavily barred, in which those charge with murder or responsibility for fatal accidents are held until the verdict of the coroner’s jury is rendered. This verdict either releases the prisoner from custody or else sends him to jail to await the action of the grand jury.

Autopsy Room and Museum

On the upper floor of the building is the autopsy room, which has been pronounced by physicians to be one of the best in this country. It is in this apartment that Deputy Coroner Glazebrook, and sometimes Coroner Nevitt, perform autopsies on the remains of those who have been brought to the morgue. There is also upstairs a small anatomical museum, which has been arranged by Morgue master Schoneberger, and contains many objects of interest to anatomists and those concerned in medical science. One of the curiosities in the museum is a baby mummy, the child having been included among the participants in a tragedy several years ago. The process by which the infant was mummified was originated by Mr. Schoneberger.

Other rooms on the upper floor are used for sleeping purposes of the morgue attaches.

Mr. Schoneberger claims that he is the originator of the morgue record book. For a long time prior to the erection of the new morgue the only records of accidents, murders, suicides and similar occurrences were contained in the incidental report made at the several police stations. The system of record keeping now in use at the morgue is said to be an excellent one.

Crimes and Casualties

Following the entries made by Mr. Schoneberger on his simple little morgue book, the first name entered upon the large morgue record book now in use was written thereon by Dr. Woodward, health officer of the District at a time when he was coroner. It is dated July 1, 1894, and this notation follows the name: “Found in Capitol Park, bottle of whiskey by his side, heat stroke.”

This book in its quaint and simple way tells a long history of the crimes and casualties of the District of Columbia. It is frequently referred to and is considered in police circles to be a book of valuable reference.

Another innovation is the morgue wagon, which was also inaugurated through the efforts of Coroner Nevitt and Morgue master Schoneberger. Prior to the adoption of this means of transportation for the dead the police patrol wagons were called into requisition to convey the bodies of victims to the morgue. As this was considered highly objectionable by the police, the present dead wagon was brought into use.

Morgue master Schoneberger has a little photograph outfit connected with the institution under his charge, and it is his practice to take picture of the dead, particularly those who remain unidentified. Many years ago he began to take pictures of the victims of tragedies in this city. He secured a picture of the dead man after Mrs. Bonine killed young Ayres. The photographs taken by Schoneberger were afterward used as evidence in the trial of the case.

Record of Deaths

The statistics of the morgue show that last year there were taken to that institution the remains of 275 persons whose death was due to accident, murder or suicide, and in addition the bodies of 168 stillborn children. During the fiscal year just ended, 406 bodies were placed on the cooling boards in the vault at the morgue, and during the same period 67 inquests were held there.

Wm. Schoneberger has been morgue master since July 15, 1892. He is a man of small stature and seems very much devoted to his ghastly occupation. Several years ago, when he presided over the little morgue at the sixth police precinct station, the suggestion was made to him that as nearly every trade and profession had an emblem, it was meet and proper that he, the District morgue master, should also have one. Schoneberger thought the matter over and a few days later he appeared at the morgue wearing a jet black necktie on the front of which was an uncanny scarf pin composed of a grinning skull and crossbones. The blazing eyes of the skull were two jewels which sparkled with a weird and unearthly glitter. The morgue master was proud of the emblem of his trade and wore it constantly until one day not long ago someone stole it from him and he informed a Star reporter that he was willing to pay a liberal reward for its return. If he does not recover the missing article he says that it is his intention to have another one made.

Sketch of Mr. Schoneberger

Mr. Schoneberger was born at the corner of Vermonts Avenue and M Street this city June 16, 1863. He was reared in the country, his father having died when he was but seven years of age. He was bound out to a farmer for nine years. He returned to Washington when seventeen years of age and started to learn the trade of butcher. He left here again in 1891 and later came back with a wife and two children, and was employed as janitor of No. 6 police station when, through the good offices of Lieutenant of Police John Kelly, he was, on July 15, 1892, designated to take charge of the little morgue at the station, at the time when the late Dr. Patterson was coroner.

Mr. Schoneberger is not unwilling to relate the queer happenings that have taken place during the time he has been master of the morgue. He says that the business has become a second nature to him, and he always welcomes visitors to the ghastly establishment under his control, and takes considerable pains in showing them through the place and explaining to them its mysteries. He had several improvements of the morgue in contemplation and says he hopes to make it better and the best institution of its kind in this country.

Although Morgue master Schoneberger deals extensively with death, frequently in its most horrible forms, he does not wear the funereal smile and grave expression which is so often ascribed to undertakers and grave diggers. On the contrary, he is of a most cheerful demeanor and always has a fund of good laughter-provoking stories in stock for his friends. In his experience here he has handled many hundreds of bodies of unfortunates. In the kindness of his heart Mr. Schoneberger has frequently had buried at his own expense some of the unclaimed dead, instead of disposing of them in the method referred to above as being “according to law.” He has taken such action when from the appearance of the remains it seemed that the persons were well reared but had probably become the victims of misfortune and had died without identification, and, perhaps, far from family and friends.

Source: Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 05 Aug. 1906.