How did Nebraskan inmates meet their end in the early 1900s? The article below, originally published in 1921, gives readers an in-depth look at the men who were hung or electrocuted for murder.

Last Hours with Doomed Murderers

By Guy G. Alexander

Published February 13, 1921

“You, ___, have been found guilty by a jury of your peers of the crime of murder. Have you anything to say before the court shall impose sentence?”

The prisoner, wan and haggard looking, the ineradicable signs of the telling ordeal through which he has passed, during the course of his trial, suddenly looks up, glances about him at the expectant faces of the crowds in the small court room and then in a voice almost inaudible answers, “No.”

“It then is the sentence of this court that you be turned over to the custody of the warden of the state penitentiary, there to be electrocuted by a sufficient current of electricity to cause death, between the hours of 6 AM and 6 PM on the ___ day of ___.”

Thus does the court and jury, of 12 good men and true, discharge their obligations to a commonwealth which they represent upon one who has transgressed the laws of the state by the commission of the crime of murder.

Jurors Fix Penalty

Murder, in legal diction the crime of premeditatedly taking human life, has since time immemorial been regarded by an outraged populace and judicial institutions of the world as the most heinous of all crimes. Murder has at some time or other in every civilized country of the world been punishable by the imposition and infliction of the death penalty.

Many there are in all climes who have in latter days railed and petitioned against this mode of punishing those responsible for the illegal taking of human life. Many states of the United States have abolished the death penalty and substituted the imposition of a life sentence at hard labor, within prison confines.

In almost every state in the union where the death penalty is still in force, the jurors sitting in the case have the prerogative of fixing the penalty either at death or life imprisonment.

In Nebraska, jurors in capital offense cases have this right. Several unsuccessful attempts have been made in this state within recent years to abolish the death penalty, but each and every attempt has been defeated. Since the admission of Nebraska into the union, the death penalty always has been upon the statute books. Since the beginning of the twentieth century all executions have been held at Lancaster, the home of the Nebraska state penitentiary. Prior to the opening of the present century, however, executions were held under. The direction of the sheriff of the county in which the crime was committed, but some 20 years ago the state legislature passed a law directing the capital punishment should be inflicted only under the direction of the warden of the state penitentiary and that all executions should be held within the walls of that institution.

Since the passage of that law, the state has exacted a toll of 10 lives of convicted and condemned murderers at Lancaster. Not such a large number, to be true, in 18 years. This represents but a small number of men convicted of the crime of murder by juries in the courts of the state during the same period, but nevertheless does show that juries in some cases still regard the death penalty as the punishment best fitted for the taking of human life.

Fight in Courts

With the imposition of the penalty of death by a presiding judge of the district court, generally begins an extended legal battle to prevent the execution of the sentence. Time and time again have lawyers of the condemned men carried their cases to the highest court of the state, on appeals, rehearings and other technicalities; there, time and time again, to be met with the order:

“To the warden of the Nebraska state penitentiary: You are ordered to carry out the mandate of the district court of the ___ judicial district in the case of the State of Nebraska against ___.”

With their last hope gone of escaping the exaction of the supreme penalty for their crimes at the hands of the courts, convicted and condemned murderers of Nebraska have unavailingly carried their appeals to the chief executives of the state to secure clemency, only to be met with a firm refusal to interfere in the execution of the sentence imposed by the courts of the state.

Last Minute Efforts

Every person executed during the last 18 years in the Nebraska state penitentiary has clung to the hope of escaping the death penalty until within but a few short hours of his death. The most recent example of this was the last-minute efforts made early on the morning of December 20 last year in the United States district court at Lincoln to prevent the execution of Alson B. Cole.

During the time from the infliction of the sentence of death by the presiding district judge until the last appeal to the governor of the state has been turned down, almost without exception condemned murderers – for murder is the only crime punishable by death in this state – have remained in their cells at the penitentiary, there to be punished by conscience.

As They Meet It

Death, that intangible something that means everything – and nothing. What is death? It stops the wheels of industry and halts the march of trade. It brings smiles to one and tears another. It is ever faithful. Above all, it is infallible. It fails no one.

To the child it means the absence of loving hands and days of darkness.

To the youth it is the end of the trail which in the morning sun stretched toward the future.

To the man it is the end of conquest or the release from failure.

To the aged it is nightfall, the end of a summer or winter day.

To the theologian it means the final reckoning and the reaping of harvest.

To the skeptic it is the great adventure, an opportunity to explore beyond the curtain.

The pauper may shiver.

The prince may hold the riches of the world and revel in the joys brought to him in his worldliness, but—

Death comes to both.

Death the end of all? The beginning of all, who knows?

Andrew Carnegie, famous for his philanthropies, his libraries, his wealth, his influence, once prohibited the mention of the word “death” in his presence.

This mighty captain of industry and fortune, not an atheist and not a man known for his Christianity, was able to prevent the mention of the word “death” in his presence.

His Sensations

Carnegie could bar the very word death, but what of the convicted felon with the stamp of death imposed upon him, as he sits or paces the floor of his tiny cell, barred on all sides, with no future, no hope, nothing but his thoughts and conscience?

What must be the feelings, the sensations, of the condemned as he stands before the bar of justice, there to hear pronounced by the presiding judge, the words that will send him to a murderer’s grave, rob him of his future life, the God-given right to life, his constitutional right to life, liberty and pursuit of happiness?

No criminal, no matter how hardened, every occupied a murderer’s cell in the state penitentiary at Lancaster, who left behind any sign or any evidence of his feelings, experienced during those last few hours that remained of his mortal life.

Walk to Death

It is true, no condemned felon over started the death march that did not have the comforting help and the kindly cheer of friends he had made either outside of, or behind the prison walls. But to these friends he could not impart his feelings, the lashing of his conscience or his hopes and fears, as he sat waiting within his cell for that tell-tale step, that he knew meant, for him, the beginning of the end.

Of the 10 men put to death, eight in the little brown shack in the southwest corner of the prison yard at Lancaster and two in the death chamber of the new hospital building, none was so completely punished by his conscience that he was unable to walk to his death. Some there were, it is true, who faltered as the prison chaplain, the warden, guards and witnesses joined the little procession at the cell house for the last pilgrimage that led to death and the great beyond, and freedom, freedom from the confines of stone walls and iron bars. With but one exception, the men put to death in the Nebraska prison, had never before served a sentence behind prison bars. To them the commission of the crimes for which they paid with their lives was the Alpha and Omega of their crime careers.

Just a Boy

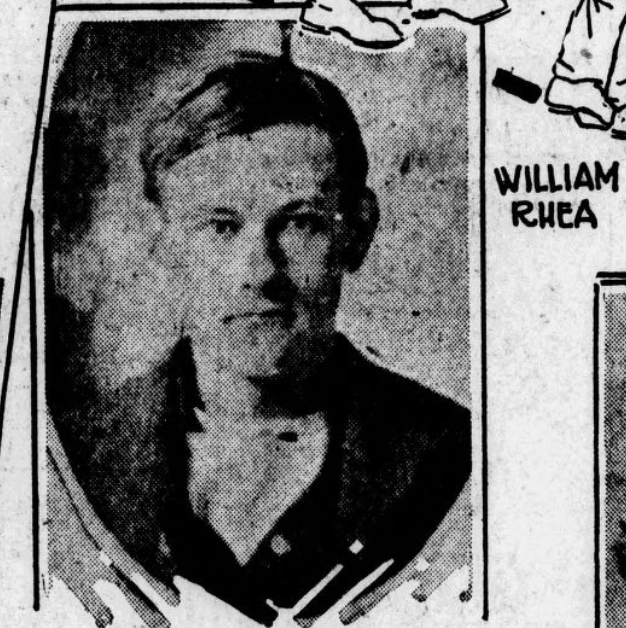

William “Rhea,” little more than a boy, with the pink of youth still upon his cheeks, was the first murderer to pay for his crime with his life at the penitentiary at Lancaster. It was on the afternoon of July 10, 1903, that Warden Beemer, Deputy Sheriff George Stryker of Omaha, then chief executioner for the state and a number of guards and witnesses entered the cell of Rhea to take him to his death.

Rhea, displaying much of the bravado that characterized the commission of the crime for which he was convicted, greeted his visitors and joined them on their walk to the gallows. He walked with a firm, steady step until he entered the death chamber. There he nonchalantly removed a light slouch hat which he had worn continuously in his cell. Looking about him he espied a guard, one who had often befriended him during his incarceration in the death cell. He lightly tossed the hat to him and then walked up the steps leading to the scaffold. There he showed the first evidence of a break in his iron composure. As the executioner was adjusting the rope about his neck and drawing it taut, Rhea, his head covered by the black cap, pleaded with the executioner not to draw the rope too tight.

Trap Sprung

No sooner had he made the request than the trap was sprung and his body shot downward. He was not pronounced dead for nearly 20 minutes after. This was due to the fact that because of his frail, slight physique, his neck was not broken by the fall. Death was caused by strangulation.

Rhea was convicted of the murder of Herman Zhan, a saloon-keeper at Snyder, Nebraska, during a holdup. His real name was Klein.

He ran away from his home in Indiana when but 12 years of age and became a jockey. He roamed throughout the entire country and was but 19 years of age at the time of the commission of the crime. His father, who had accumulated enough of this world’s goods to spend his declining years in comfort, spent every dollar he had searching for his son after he ran away from home, but was unable to find him until he was occupying a murderer’s cell in the penitentiary.

“All Ought to Be Killed”

While awaiting trial in the county jail at Fremont, Rhea had a visitor, George Howe, a saloon-keeper of Fremont. Rhea expressed himself as being glad that he had killed Zahn and ended his conversation with the remark that “every saloon-keeper should be killed.” Howe retaliated by saying he would see his execution for that remark and, but a turn of fate, Howe was one of the official witnesses, along with a brother of the murdered man, at the execution.

Rhea’s companion in the holdup and murder, a man by the name of Gardner, was sentenced to life imprisonment. Gardner is in the penitentiary today.

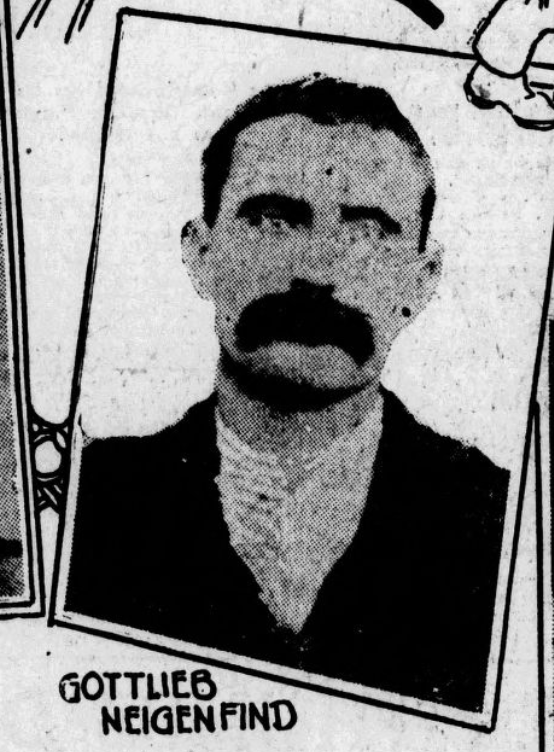

The second felon to die within the little brown shack at the prison was Gottlieb Neigenfind, convicted in Pierce county of murdering his wife, from whom he was estranged, and he brother, Albert Breyer, a farmer residing near Pierce. The murder occurred on the afternoon of September 1, 1902.

Captured by Posse

Neigenfind had made repeated efforts to see his small son, who had been given into the custody of his divorced wife. Repeated efforts to see his babe met with rebuffs from his wife and her brother. Finally, he shot and killed his wife and then shot and killed her brother who, attracted by the shots, had come to her rescue. He then started to flee from the scene of his crime, but encountered his wife’s sister. Beating her with the butt of the revolver which he carried he finally escaped from the farm, only to be captured a day or so later by an armed posse of neighbors. Neigenfind himself was wounded before he finally surrendered to the members of the posse.

Convicted and condemned to hang, Neigenfind was removed to the penitentiary, while his attorney’s made several futile efforts to secure a commutation of sentence. Neigenfind was a model prisoner during the time he was confined in the prison and even during the walk to the scaffold he maintained the solemn composure which had marked his every hour within the prison walls. He spent the time in the death cell in reading and writing. At no time during the march from his cell to the scaffold or upon the gallows did he make any statement or show any signs of a physical collapse.

He was executed September 5, 1903.

Brutal Slaying

Early in January in 1908, or on the 17th of that month, to be exact, Frank Barker, convicted in Webster county, died upon the scaffold for the murder of his own brother and sister-in-law, a crime regarded by many criminal lawyers and criminologists as being the most brutal in the murder annals of the state.

Barker, a young farmer boy, was convicted in 1904 of the murder of his brother, Dan, and his wife in their farm home near Inavale. Barker, according to testimony adduced at his trial, was engaged to marry a young girl of his acquaintance, the daughter of a farmer residing near the home of Barker and his brother.

Dan, the older of the two boys, was married and through constant application to work had accumulated a small competence and a highly improved farm on which he made his home. Barker was employed by his brother part of the time, and the remainder of the time worked for other farmers in the immediate neighborhood. On the night of February 1, 1904, at about 10 o’clock he called at the home of his brother, Dan.

Knocking at the door, he attracted the attention of his brother and as Dan opened the door to greet him he was slain by the discharge of a gun held by his brother, Frank.

Shoots Sister-in-Law

Stepping over the dead body of his brother, Frank calmly walked into the house, made his way to an upstairs bedroom where the wife of the murdered man was preparing to retire and without a word pointed the gun with which he had killed her husband at her and shot her down.

Then he carefully carried their bodies out of the house to the rear of a barn and with the aid of a lantern, buried them in a shallow grave which he dug. He spent that night in the home of his murdered relatives and remained in the neighborhood for several days. When the disappearance of his brother and his wife became known, Barker, questioned, told several different stories which finally resulted in his arrest, his subsequent conviction and hanging.

Meets Death Calmly

During the four years he spent in the penitentiary after the commission of the crime and execution, Barker never once was confined in the death cell. He occupied a cell, the same as ordinary prisoners, worked with them in the shops and enjoyed the privileges they enjoyed. At no time during the full four-year period did Barker collapse and show any outward signs of remorse for his crime. He bravely walked to the gallows and with the same air of bravado that had marked his every action, stood calmly while the hangman’s knot was fixed, the black cap adjusted and the trap sprung.

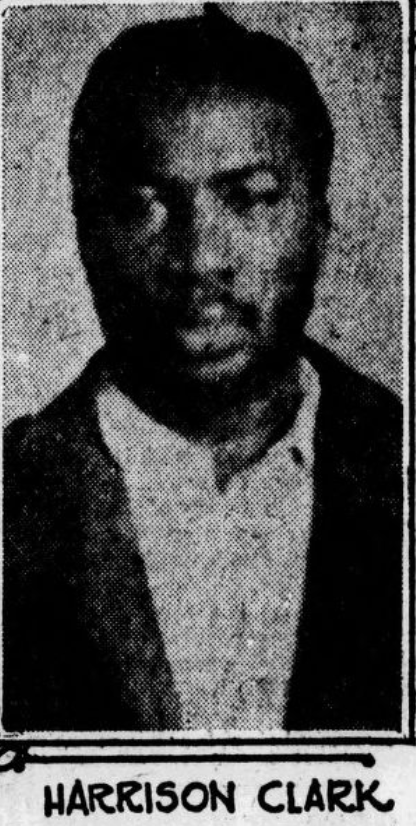

But one month before the execution of Barker, Harrison Clark of Omaha, was executed for the murder of Edward Flurry, a street car conductor of Omaha.

Flurry was murdered on the night of March 8, 1906, at the Albright street car “Y” during a holdup. He died nine days later in a local hospital.

Plays Guitar

During the time that he was held in the prison, Clark contented himself with the strumming of a guitar which Warden Beemer permitted him to keep in his cell. At no time did he display any emotion or remorse for his crime, but at every opportunity he protested that he was innocent of the crime for which he was convicted.

Immediately following his last meal Clark called for a cigar, which was given him. Shortly after, while talking with newspapermen, he delivered a speech in which he warned against the use of intoxicating liquor. Following this he picked up his guitar and continued to strum it while waiting for the arrival of the guards to start the death march.

As he left his cell on the way to the gallows, he continued to puff on his cigar. He puffed the cigar on the scaffold while his arms and legs were being tied by the executioner’s assistants and did not throw it away until the black cap was pulled down over his face.

“Hanging Innocent Man!”

With the placing of the cap over his eyes, he displayed the first signs of a collapse. Screeching at the top of his voice, he said:

“I want a bag with something heavy to put on my feet.” He repeated this request several times and then with a final effort cried out:

“Goodby everybody. You’re hanging an innocent man for a crime he never committed. Tell my mother to pray for me.” As the sound of the words from beneath the black cap died away, the trap was sprung and 13 minutes later he was declared dead by the prison physician.

R. Mead Shumway followed Frank Barker to the gallows. Shumway was condemned to die for the murder of Mrs. Sarah Martin, wife of his former employer in Adams county on September 3, 1907. He was executed on March 5, 1909.

Shumway had been employed as a farmhand for four days on the farm occupied by his victim and her husband. On September 3, Mr. Martin drove to town leaving his wife and Shumway at the home. Upon his return he found his wife had been murdered and the farmhand missing. He spread the alarm but Shumway managed to make his escape. He finally was located in Missouri, where he was working on a farm. He was well known in the community where he was captured and no trouble was experienced in finding him after the murder.

Snatched from Gallows

He was returned for trial, was convicted and sentenced to hang. Six times he literally was snatched from the gallows by reprieves granted by the governor. A legal struggle almost unprecedented in the criminal courts of the state was waged in an attempt to have him, but death was the final victor.

Shumway protested his innocence from the time of his arrest and his last statement, made from the scaffold was:

“May God forgive all of you who have had anything to do with me, for you are hanging an innocent man.”

The trap then was sprung and 27-1/2 minutes later he was pronounced dead. Death was due to strangulation, he being of too light a physique to cause death by breaking his neck by the fall.

Captured in California

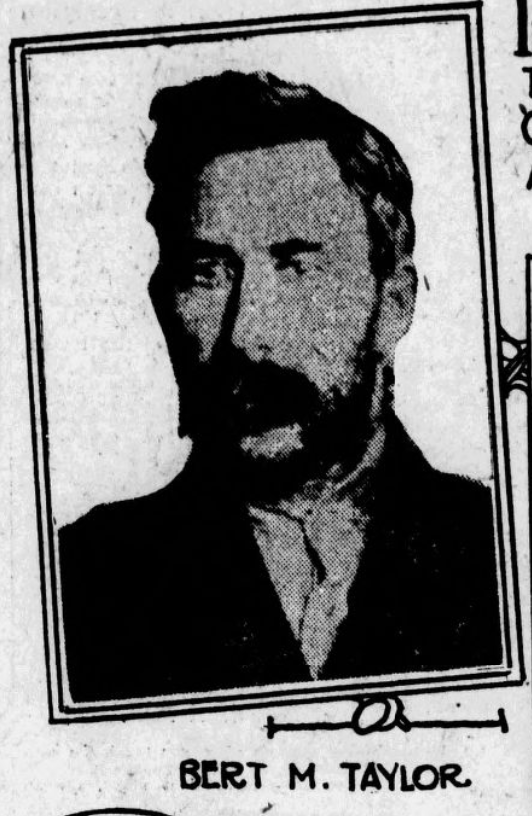

On October 10 of the following year Bert M. Taylor was executed for the murder of the two unmarried sisters of his dead wife at their home near Minden. Taylor was captured in California after a chase of several months’ duration. He was convicted of the murder and burning of the home of his sisters-in-law in an effort to cover his crime. No signs of malice or of physical collapse marked his appearance on the gallows before his trap was sprung.

Thomas Johnson of Omaha, 18 months later followed Taylor to the scaffold. He was convicted of the murder of Henry Frankland, a transient in Omaha. Frankland was found murdered under the Tenth street viaduct, near the Union station. The murder was committed on the night ofOctober 3, 1909. Frankland was returning to his home in Chicago from Montana, where he had been working, and was supposed to have considerable money on his person. Robbery was proven at the trial of Johnson to be the motive for his crime. Johnson during his incarceration displayed no signs of remorse and joined in the daily work of the convicts at the penitentiary the same as a convict serving but a short term.

Converted in Prison

Johnson, however, was acquainted with prison life, for he had been liberated but a short time before the murder from the penitentiary where he served a short term. Johnson’s 9-year-old son was an almost daily visitor with his father at the prison while he was waiting for the day of his execution.

On the way to the “death house” Johnson kept muttering prayers, but made the walk without effort. On the scaffold he made his farewell statement, which was “Goodby, meet me in heaven.” Johnson had been converted while an inmate of the prison waiting execution.

Following Johnson on the scaffold was Albert Prince, also of Omaha, the last man to be executed in the state penitentiary by hanging. Shortly after his execution on March 21, 1913, the state legislature substituted electrocution for hanging.

Kills Warden

Prince was convicted at Lincoln of the murder of Deputy Warden Davis on February 11, 1912, while he was serving a sentence of 12-1/2 years. The murder occurred in the assembly room of the prison. Davis, who was on duty in the assembly room, was stabbed by Prince as he passed him on his way out of the room to go to his cell. The murder was committed with a knife stolen from the broom factory. Davis was so seriously wounded that he died a few hours later.

The murder preceded the outbreak of “Shorty” Gray and his gang, with their subsequent murders, by about six weeks.

Prince spent his last days in the death cell writing poetry. His final statement, aside from several letters and poems that he had written while in the death cell, was: “When I fall to my death my soul will go straight up to heaven.”

Taken After Gun Battle

Thirteen minutes later he was pronounced dead, and once again the state had exacted the extreme penalty for the commission of murder in this state. Prince was a man with a bad record. He came to Omaha from Kansas City, where he was suspected of having committed many burglaries. He was captured in an Omaha saloon by a policeman who recognized him from his picture, but was taken only after a running gun fight.

Thus ended legalized hangings in Nebraska and in place was substituted the so-called “more humane” method of inflicting the death penalty.

Alson B. Cole and Allen Vincent Grammer, whose long legal fight to escape the chair is too well known to Nebraskans to be repeated here, were the first and so far, the only murderers in Nebraska to pay with their lives in an electric chair for the commission of the crime of murder.

Cole and Grammar were executed December 20 of the last year more than four and a half years after the body of the woman for whose murder they paid the supreme penalty, was found slain near Elba, Nebraska. Their fight for their lives from the justice court to the Supreme Court of the United States set a record for legal fights in an effort to escape the death penalty.

Four years after the murder of the aged Mrs. Lulu Vogt, two men paid the supreme penalty. An outraged state had exacted payment for the breaking of one of its oldest laws, and once again had the scriptural text, “an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth” been fulfilled.

The does the state inflict the death penalty, and whether its exaction serves its purpose to act as a deterrent for others, I leave to the best judgement of those who read this.

Source: Omaha daily bee. (Omaha, Neb.), 13 Feb. 1921.