A fascinating look into the possibility that “falling stars” may have sunk a few ships and wiped a few airships out of the sky.

While the science is certainly dated, the 1930 article below does cover a few mystery ships and some interesting large meteorites.

Destroyed by Falling Stars

Did a meteorite, traveling at the well-nigh incredible speed of 30 miles a second, erase forever from human ken the monoplane Golden Hind and its pilot, “Cowboy” Urban F. Ditteman, who recently soared into the blue, London-bound, from Harbor Grace, Newfoundland?

Is there a possibility that death-dealing visitors from interstellar space were responsible for the mysterious disappearance of the tragic list of transoceanic planes – Nungesser’s White Bird, the Old Glory of Bertaud and Hill, the Hon, Elsie Mackay’s Endeavor, Mildred Doran’s Honolulu-questing craft, the Sir John Carling, and Roald Amundsen’s giant seaplane?

Did “falling stars,” as the rank and file term the metallic fragments with which the earth constantly is being pelted, possibly account for the loss of the French Zeppelin Dixmude, the United States Navy collier Cyclops and the Danish training ship København?

“Yes,” says Gen. Frederic Chapel, noted French astronomer and meteorologist, who for years has studied the phenomena of meteors and meteorites.

“It is common knowledge among scientists,” says Gen. Chapel, “that from 70 to 4,000 meteorites plunge each year to our earth. If we could check accurately how many fall into waste stretches of the great oceans, unobserved, the number undoubtedly would reach a much higher figure. Is it not possible some of the missing sky and sea craft were wiped out by these aerial visitors?”

The French expert goes further. He asserts numerous mysterious explosions on land, forest fires, even bad weather, may be due to the whizzing fragments coming to us from disintegrating planets untold millions of miles distant.

Meteorites Sizzle Through Space

“Red-hot meteorites,” asserts this noted Frenchman, “literally sizzle through space. It is entirely probable their passage sets up electrical disturbances in the comparatively thin envelope of atmosphere surrounding our earth. Such disturbances may cause atmospheric changes and attendant bad weather.

“As for the power of meteorites, regardless of size, to destroy earthly objects they may strike, it has been calculated that a meteorite weighing about 2 ounces possesses the potential force of a 500-ton train as it strikes the terrestrial sphere at a speed as high as 30 or 40 miles per second.”

Meteorites Killing People and Damaging Buildings

Have there been instances, one asks, of meteorites killing persons or damaging buildings?

There have. Only a few months ago an18-year-old Hungarian girl of a farming district near Budapest left her home one starlit night to attend a wedding taking place on a neighboring estate. Eyewitnesses to the tragedy described what happened. A “falling star” screamed in a wide parabola to earth. It struck the road at a point where, a moment before, the girl had been observed walking. Her mangled body was found sprawled in the dust. Seared fragments of a metallic substance were scattered about, later being identified as meteoric matter.

In 1917 a falling meteorite partially wrecked a house in the Strathmore district of Scotland. Residents believed at first they had been the target of a raiding German Zeppelin. Then tests were made and the metal fragments were revealed as pieces of a meteorite. History records a similar incident in 1847, when a house in Braunau, Bohemia, was shattered by a “falling star,” which came to rest on a bed in which three small children were sleeping.

Three years ago what unquestionably was a giant meteorite fell in a densely wooded district of Western Siberia. It exploded upon landing, the detonation being heard many miles. Investigators found a smoking area 3 miles wide and 7 in length from which every vestige of trees had been wiped away. Meteoric fragments were found all about.

Canon Diablo

Then there is the famed Canon Diablo, in Arizona, known to many by the prosaic name of Coon Butte, which scientists are convinced marks the resting place of probably the largest meteorite ever falling in the United States, if not on the whole earth. It is a vast basin 4,000 feet across, 550 feet deep at its center and surrounded by a limestone “lip” 100 feet above the surrounding plain. Meteorite fragments have been found all about, and it is believed the mother mass of metal lies buried beneath.

Borings have failed to locate the mammoth meteorite, but pictures taken from the air indicate the great missile struck at an angle and may lie some distance to one side of the actual crater ring.

Other Meteorites

Comdr. Robert E. Peary, returning from one of his polar expeditions, brought back three meteorites, the largest of which weighs 37-1/2 tons. Among the Eskimos of Melville Bay, Northern Greenland, it was known as “Ahnighito” (the Tent). The two others were known as the Woman and the Dog. For years natives had been chipping off pieces of them from which to construct their knives.

According to the tale handed down from their forefathers, evil spirits had cast the great masses down from the heavens.

Peary brought the three meteorites to New York. The Tent now rests beneath the entrance arch of the Museum of Natural History.

Another famous meteorite, the Bacuibuito, so called from the town in the State of Sinaloa, Mexico, near which it fell, is estimated to weigh in the neighborhood of 50 tons. This weight is only approximate, as the great clot of fused iron and quartz never has been raised from its resting place.

Destruction

Did a giant interstellar fragment, such as those mentioned, destroy the United States Navy collier Cyclops?

The Cyclops, a vessel of 19,360 tons and by reason of its construction capable of delivering coal to a warship at sea at a rate of 1,440 tons per hour, left the Barbados on March 3, 1918, bound for Norfolk. She carried a cargo of manganese, and was commanded by Lieut. Comdr. George W. Worley. Her personnel consisted of 15 officers, 221 men and 57 passengers, many of the latter Navy officers and men returning home for assignment.

After she cleared the islands nothing further was heard of her. Not a body, not a particle of wreckage ever was found. She carried one of the most powerful wireless outfits in the Navy. Had she run into a storm or been mined or torpedoed, as many suggested, it seems almost impossible she could have sunk without some sort of SOS being flashed.

Yet there was no distress call of any kind.

After the war the Germans denied all knowledge of her fate, apparently shattering the mine and torpedo theories. Was it a meteorite that erased her from the face of the Atlantic?

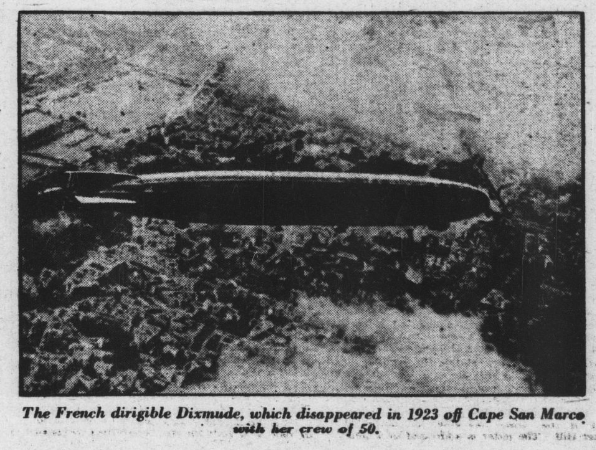

Dixmude

On December 18, 1923, the French airship Dixmude left her hangar at Cuers bound for a cruise to the north coast of Africa, under the command of Lieut. Du Plessis de Grenadan. She carried a crew of 50. Gales sprang up when she arrived over Africa. She was unable to land, due to lack of ground crews and hangar accommodations.

The Dixmude, formerly the German Zeppelin Nordstern, was last heard by wireless on the night of December 21, when southwest of Algeria, she flashed the statement she was returning to Cuers. The following night persons in Sicily reported seeing two great balls of fire slowly descend into the Mediterranean – “like a pair of balloons on fire.”

Two days later Sicilian fishermen, raising their nets off Cape San Marco, found a French naval officers body. It was Lieut. Du Plessis. Next day they found an empty gasoline tank, later identified as belonging to the Dixmude; a mass of tangled wires believed to be part of the airship’s radio, and several burned fragments of rubberized balloon cloth and scorched human flesh.

Nothing more was recovered.

The Dixmude was recorded as having been destroyed by lightning. That guess may have been wrong. It may have been a meteorite.

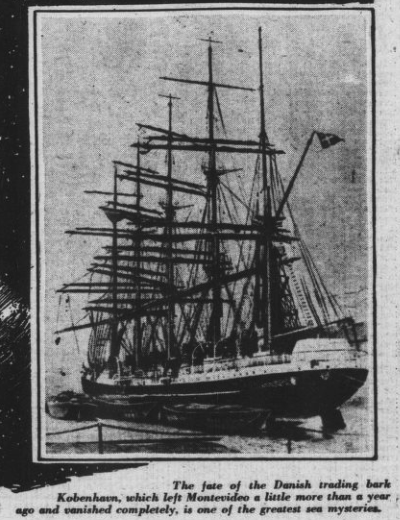

København

On December 14, 1928, the Danish training ship København, owned by the Eastern Asiatic Co. and manned by sailors and cadets to the number of 50, sailed from Montevideo on an 8,000 mile voyage to Melbourne. She was a trim, five-masted bark, with a steel hull, an auxiliary power plant, and a modern, powerful wireless.

From the time she cleared Montevideo no call was picked up from her. She sailed silently, mysteriously, into oblivion.

In June of last year her owners sent the steamship Mexico on a search for the lost vessel. The Mexico combed the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans, visiting Tristan de Cunha and the treacherous Avocet Rock, on whose hidden reefs lie the bones of many gallant ships. Not a trace of the København was found. A storm could have wrecked her; a rock might have ripped out her bottom. But why were there no distress signals?

Perhaps a “falling star” sent her, crushed and shapeless, to the bottom in the wink of an eye.

An interesting theory on the fate of the København has recently been advanced by waterfront seers in Copenhagen, who ascribe the disappearance of the training ship to the fact that some of the 48 cadets aboard had captured an albatross before the ship cleared for South America. They draw a close parallel between this modern ship and the one which figured in Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

Source: Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 23 Feb. 1930.