Shifflett was hanged twice for the murder of a man he was paid to kill.

Shifflett’s Execution

Horrible Gallows Scene in Virginia

HARRISONBURG, Va., September 25, 1877 – Anderson Shifflett was hanged in the jail yard at this place today for. The murder of David G. Lawson on March 15, 1875. There were about 60 persons present at the hanging.

Shifflett had passed a very restless night, and had refused to eat breakfast. He was shaved and dressed in a new suit of cashmere at 8 o’clock. Immediately thereafter the sacrament was administered to him in his cell by the Rev. David Barr, rector of Emanuel Church. There were also other religious services conducted by the Rev. Mr. Barr and the Rev. Mr. Eggleston of the Methodist Church.

At 9:25 o’clock Sheriff Ralston entered his cell and told him that it was time to go. Shifflett replied, “I am ready.” He was supported as he walked through the corridors and jail yard by the Rev. Mr. Barr and the Sheriff.

After Shifflett was seated on the scaffold, the Rev. Mr. Barr asked him if he had anything to say. He replied, “No; you read that.”

Mr. Barr then read the last dying statement of Shifflett as follows:

“I, Anderson Shifflett, do, on this 25th day of September, 1877, make the following statement, and call God to witness that it is true: About four weeks before the murder of David G. Lawson, Samuel Hall offered me about $25 to kill Lawson or put him out of the way some way. I refused to do it. I did not kill Lawson. When he was killed I was on a knoll fully three-fourths of a mile away. I expected he would be killed that day, and went to hear the shot fired, and did hear it. I had not been there more than 10 minutes when the shot was fired. I do not know who fired the shot. After Lawson’s death, Sam Hall gave me $2 or $3 not to tell that he offered me money to kill Lawson. Neither did Silas Moore persuade me, nor Louisa Lawson pay me or offer to pay me any money to kill Lawson. Mrs. Lawson one time said to me, ‘If you were to do it you would be paid for it; but I have got no money.’ This is my last dying testament. And now, praying the merciful God to forgive all my sins, and looking to Jesus Christ for salvation, I say farewell.”

During the reading of this paper Shifflett sobbed aloud, frequently calling on God to witness that he was innocent. At the conclusion of the reading Mr. Barr shook hands with him, and Sheriff Ralston asked him to stand up. While the Sheriff and deputies were pinioning him, Shifflett repeated many times that he was innocent, and, as the black cap was drawn over his face, called upon the Lord Jesus Christ to have mercy on his soul.

At 9:45 o’clock, the rope sustaining the trap was cut. As Shifflett fell, the gallows rope (a cotton one, 3/8 of an inch thick) broke with a snap resembling the explosion of a percussion cap. Shifflett dropped into the pit under the scaffold.

There was not a sound for 43 seconds. Then Shifflett said, in a feeble voice: “Oh, Lord, you know I am innocent; why must I suffer?”

He was lifted out of the pit and laid upon the grass. He turned upon his face, and for several minutes moaned piteously.

At 10:03 o’clock another rope, a hempen one, 5/8 of an inch thick, had been placed in position, and Shifflett was carried by three deputies to the scaffold. He again prayed loudly, asserting his innocence.

After the black cap had been placed over his face the second time, he asked that it might be removed so that he could see daylight once more. When his request was complied with he said, “Gentlemen, good-bye. I am innocent. May the Lord Jesus Christ have mercy on me.”

At 10:09 the drop again fell. Shifflett struggled violently for several minutes.

At 10:22 o’clock he was pronounced dead. The body was cut down, placed in a coffin, and given to his brother to be taken to his former home in the mountains for burial.

The story of the crime is as follows:

Shifflett lived in a narrow gorge of the Blue Ridge, known as Shifflett’s Hollow. It is a wild place, inhabited by people who know of churches and schools only by report, and among whom legally solemnized marriage is the exception. Shifflett’s Hollow has always borne a bad name. Desperadoes of every class seek an asylum there from the law. The people hunt in the winter months; in the summer they occasionally come down into the settlement and help get in the crops. They till a few acres of land, just enough to raise corn sufficient to keep them in bread. Yet their immediate neighbors in the mountain are, as a general thing, very excellent people, industrious, kind-hearted, church-going citizens.

David G. Lawson was a farmer, owning some 300 acres, about two miles from the Hollow. He had married a sister of one Silas Morris. Two children were born, both boys, now 12 and 16 years of age. About five years ago Lawson seduced a neighbor’s daughter, Beckie Hall. He moved her and her child into a tenement house owned by him, standing within twenty yards of his residence. Mrs. Lawson thereupon took Sam Hall, Beckie’s brother, as her lover. Quarrels were frequent, On several occasions Lawson whipped his wife.

In the winter of 1874 Mrs. Lawson determined to have him killed. She consulted her brother, Silas Morris. He promised to kill her husband for her if she would give him a house and four or five acres of land. She consented to his terms. Morris persuaded Lawson in November, 1874, to go hunting with him. He had an opportunity to shoot Lawson, and “drew a bead” on him, but his heart failed him.

He then visited an old fortune-teller, in company with Anderson Shifflett (they had to travel about forty-five miles), to get her to put a spell on Lawson. The fortune-teller promised to do so, but said it would require six months to cause death, and that she would have to have fifty silver half dollars as her fee. It is in evidence that on their way home Morris told Shifflett what the affair was, and that Shifflett said: “I will kill him for twenty-five dollars.”

Morris told him to wait a few days and he would let him know. He consulted his sister in reference to the employing of Shifflett, and she told him to do as he thought best; all that she wanted was to have her husband killed. Morris then employed Shifflett.

A few days later, if the testimony is trustworthy, Shifflett met Burriss Williams and took him in as a partner in the job. Morris, Shifflett and Williams decided to have a log-rolling, invite Lawson, and kill him by rolling a log on him. The attempt was made, but the log did not roll in the right direction.

At another time, aa Lawson was walking behind his wagon along the road, Shifflett attempted to shoot him. but the cap of the gun snapped.

Time was flying; the first of April – general moving day in this section – was fast approaching; Morris wanted his house to occupy. He hurried Shifflett up, and on Monday evening, March 15, 1875, about 4 o’clock, Morris and Shifflett secreted themselves in a clump of pines and bushes, and awaited Lawson, who had gone to mill. In a few minutes Lawson came along. A shot was fired, and Lawson fell to the ground. The ball had passed through his body, lodging between his vest and coat.

The report attracted the attention of two men, who had been with Lawson some minutes before. They found him dead. One remained with the body, and the other went for assistance, and to inform Lawson’s family. Mrs. Lawson merely asked whether they were certain he was dead, and remarked that some one had better go for a coroner.

After the inquest and funeral, Sam Hall took charge of the Lawson farm. Last winter Mrs. Lawson, noticing that she was losing her hold on Sam’s affections, offered to make a will, deviating everything she owned to him, if he would marry her. Sam promised to marry her as soon as the will was made. After it been drawn by a country squire, the detectives pounced down on Sam. He denied all knowledge of the manner of Lawson’s death, and promised, if given a little time, to work up the case, if the widow know anything about it.

He was shadowed and allowed his liberty. He began by insisting that the will be put on record. She said there would be time enough for that after he had married her, and there was a quarrel.

A few weeks afterwards Sam called on her and told her that the officers “suspicioned” him because of the will, and he was in danger of arrest. She then told him the whole story, and asked him to tell her brother, Silas Morris, to make his escape, “as the people were making a fuss about Dave (her husband) being killed.”

Sam carried the message and Morris said to him: “They cannot do anything with me for what I done. I only paid Anderson Shifflett. He done the shooting.”

Sam then informed the officers, the parties were arrested in February of this year, and at the March term of the county court the grand jury found true bills against Anderson Shifflet as principal and Silas Morris, Burriss Williams and Louisa Lawson as accessories before the fact.

Shifflett had his first trial at the April term of the County Court, and was convicted. His counsel appealed to the Circuit Court and obtained a new trial. At the July term he was again convicted, and sentenced to be hanged on Sept. 25.

Silas Morris had his first trial at the June term, the jury standing eleven for conviction and one for acquittal. He had his second trial at the July term, was convicted, and sentenced to be hanged with Shifflett, but the Governor has reprieved him to Oct. 24.

Louisa Lawson had her trial at the August term, was convicted, and sentenced to be hanged on Oct. 30.

Burriss Willams was released on bail, and used as a witness.

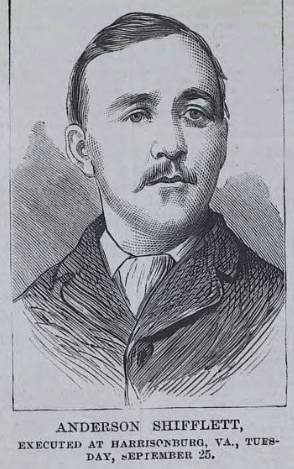

Shifflett was a slight-built man about 40 years of age, of a most villainous countenance. He was stoop-shouldered, and had a stealthy way of walking. He was married in his cell to a woman named Susan Gladdon, by whom he had had five children. The ceremony was performed four weeks ago by the Rev David Barr, who also administered the rite of baptism to him on Sunday last.

Source: The Illustrated Police News. Volume 22, Issue 571. October 6, 1877. Illustrated Police News Publishing Company (Boston, Massachusetts), 1877.