Stepping into history can often bring about a mix of awe and fascination. For instance, when we delve into the stories of seafaring adventures, we often find tales of grandeur and heroism. Yet, beneath the sweeping tales of naval battles and sea-crossing feats, a darker and far grittier reality lurks in the bowels of the great ships. In the stokeholds of these nautical giants, men faced conditions that were harsh, grueling, and often life-threatening.

The narratives we will read today may not feature prominently in mainstream maritime history, but their stories were as vital to the vessel’s journey as the wind in its sails.

This article presents four dramatic accounts of life in the ship’s stokehold, shedding light on the lesser-known heroes of maritime history.

1. Madness in the Stokehole

“Speaking of madness, that is one of the things we always expect from the stokehole,” says a writer in the Detroit Free Press. “Night is the time when such troubles break loose. The men lie awake and brood and think while the tossing of the ship makes them still more uneasy and the prospect of the next watch in a temperature of 140 degrees takes the heart out of them. Then it is that the poor chaps go out of their minds. They rush on deck and instinctively seek relief from the pent-up heat in their shattered bodies by plunging overboard.

“But such things must be kept from the ocean traveler, who expects in these days not only a quick trip with all the hotel comforts thrown in but also to be spared annoyances of even the most trivial kind.” [Source]

2. Hot Times in the Stokehole

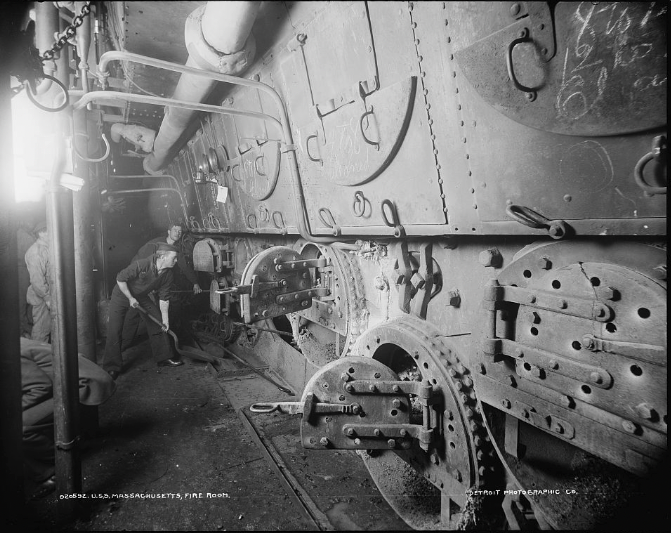

If a landsman wants an experience that he will not forget soon, let him go down into the stokehole of a warship. Then he will realize, indeed, what it means to be in the bowels of a vessel, and, to an extent, what it means to be buried alive.

If he can face the roaring furnaces without shrinking and stand in the steel walled pit without feeling dread, he will be a man of rare nerve.

Sunk in a shaft twenty feet below the sea, men toil amid fierce fires whose flames in that confined space lick out at them with every movement of the long steel slice bars that are used to feed the gaping furnaces, as savage caged beasts are fed, and, like the beasts, the fires are raging to kill the men who master them only by desperate labor.

There is no room to spare on a modern ship. Therefore the might furnaces are so crowded together that the men who serve them have barely space to move to and fro before them. So near them are the stokers and the firemen that until their skins are hardened to it they blister and crack with the heat.

The chance visitor can bear it only a few minutes. [Source]

3. Unknown Heroes

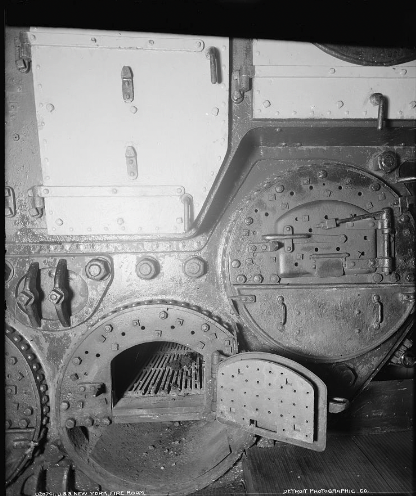

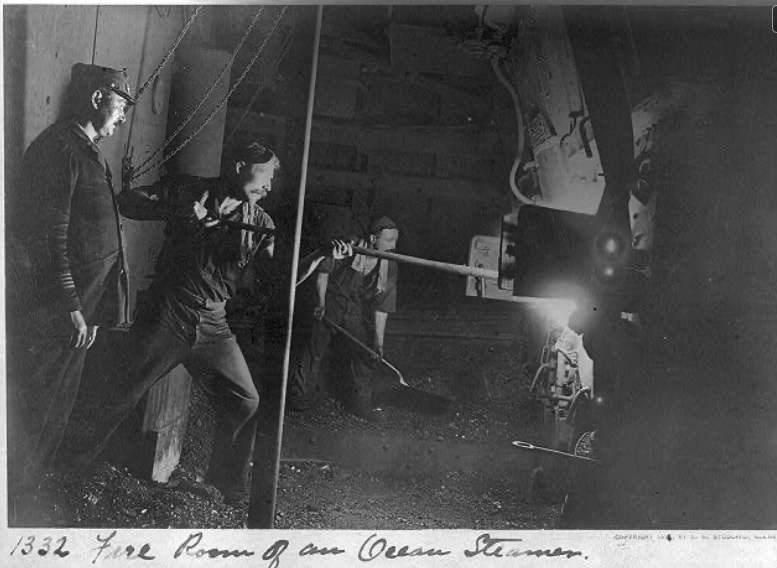

Every time one of the red-hot disc that serves as a furnace door is opened, the terrific fires within seem about to leap out to destroy the ship. Fine gray ashes make a film in the air, and suffocate one. The air that is forced into the stokehole from above catches the heat so quickly that it is shriveled almost as soon as it comes from the vent of the blowers.

Slice bars and shovels are too hot for any hand except that of a hardened fireman to touch. There is nothing to be heard of the sounds of the sea or of the rushing of the ship. Noises are plentiful, but they are the noises of soughing flames and of groaning machinery. [Source]

4. The Stoker’s Part

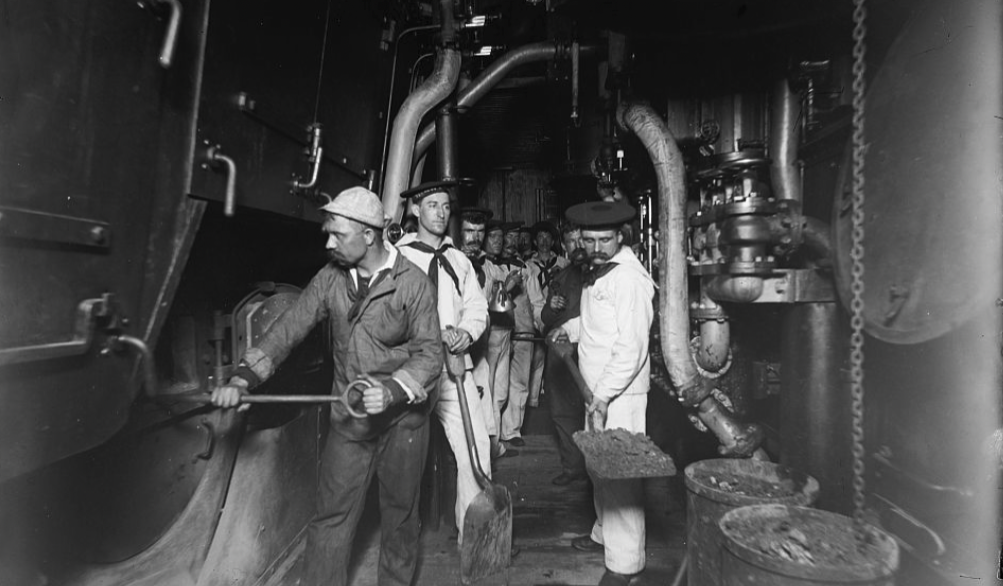

When you read of a naval battle where deeds of valor are done and glory winning courage is shown, don’t forget the faithful stoker who kept the fires hot and did his duty just as calmly as if the fact that each shovelful might be the last never occurred to him.

Up on deck where the fighting is done, each man knows just how the battle is going. He is cheered when a shot strikes the enemy and knows that if his own ship goes to the bottom he will at least have a chance to keep afloat until he can be picked up.

But the stoker goes into battle under different conditions. Down in the steaming, dusty, gloomy stokehole he sees or hears nothing that will give him an inkling of how the fight is going. Stripped to the waist, gasping for breath and sweating rivers, he throws the coal into the fiery maw of the furnace and trusts blindly to luck.

However the conflict above him may rage, the stoker hears only its distance murmur and feels only the shick of the shells’ impact themselves against the steel sides and the great funs recoil from the thousand pounds of steel and powder hurled at the enemy.

Perhaps a chance shot may pierce the ten inches of armor that guards the engines and boilers, and the rushing waters may drown him as he vainly seeks to escape.

Perhaps the 50 tons of explosives in the magazines may be reached by a projectile from the enemy’s guns and he may be blown to pieces in the steel cell where he is at work.

At any time the crisis may come, and small chance is there for him to catch on the floating spar or wreckage. In such cases the stokehole always proves the coffin of the men who feed the furnaces and lend the initial assistance toward making the war vessel a thing of life. [Source]