The following piece examines how military medicine has evolved from times when the fallen soldier was largely left to fend for himself on the battlefield, to a period when skilled rescue personnel were expected to follow close on the heels of the combatants.

The development of the rescue corps from a disregarded extension of the army to an essential, well-structured organization underscores not just humanitarian progress but pragmatic efficiency as well.

It was discovered that investing in a wounded soldier’s immediate rescue and treatment was economically more beneficial than training a raw recruit in their stead.

The article takes us through the arduous journey of the wounded from the front lines to the rear dressing stations and hospitals, giving due credit to the brave “company bearers”, non-physicians trained to provide lifesaving first aid under perilous circumstances. With their quick thinking, and resourcefulness, these unsung heroes of the battlefield played a key role in saving countless lives, often at great personal risk.

The narrative reminds us of the significant advances made in battlefield medicine and the indomitable spirit of those who brave the chaos and danger to serve their fellow soldiers.

The First Aid Man

May 9, 1898 – When a soldier of today falls wounded on the battlefield, he has many more chances of surviving than he did when we fought our last war. Methods of rescuing have been improved as well as those of killing. This has not been brought about wholly through humanitarian influences. There is a practical and utilitarian side. It is cheaper to save and patch up a trained and seasoned soldier than to let him die, pension his widow and have the bother of training a raw recruit to take his place.

Twenty-five years ago the hospital field corps was an incidental adjunct of the army. It was ridiculously small. It was unorganized. It received but little attention from the military authorities.

Today the rescue corps is well trained, fully organized, ample in size and is regarded as an important factor of the army.

In our Civil War the wounded soldier was generally left to take care of himself where he fell until after the engagement. Many a poor fellow in blue or gray might have been still alive could he have received timely and intelligent assistance.

Today the doctor follows close on the heels of the fighter, and when the latter falls the pill man is there to plug the bullet hole.

The organization for relief work in the United States army is much the same as that in the armies of other civilized nations. When a soldier is disabled in action, probably the first man to help him is one of the “company bearers” of the hospital corps. There are four of these in each full company.

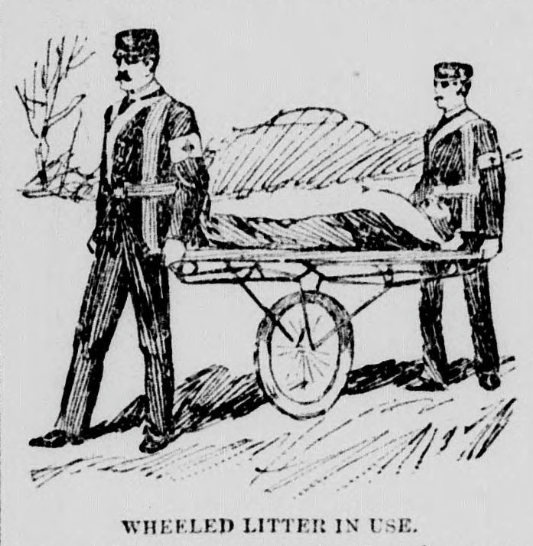

The bearer administers such “first aid” as is practicable on the spot and then assists the wounded man to the nearest dressing station or field hospital. Later he is taken in an ambulance back to the permanent field hospital, and from there he is shipped still farther to the rear, where he is sent to a general hospital, or if the base of operations is on the seaboard to a hospital ship.

As he progresses toward the rear the wounded man finds a great improvement in the mode of treatment. In the field hospital, for instance, he is laid out on the ground under a tent, but when he reaches the general hospital, he has the benefit of everything that skill and science can furnish.

But it is the first aid which is the most important, and the men who render it are the most interesting. The class of men who are to become the heroes of tomorrow are the company bearers who go about their business of rescue and relief just behind the line of battle with the bullets zipping about their ears. They are not physicians, but they are men who can do all that a doctor could do under the circumstances. They are trained for the work.

Each company bearer carries a small leather pouch that contains dressings, bandages, plaster, pins, and other small things. These are simple tools with which to do serious work, but the company bearer must know how to use makeshifts, and he does.

If a leg bone is shattered, he grabs up a stray stick or a bayonet, rips a sleeve from a coat and puts the limb in something that answers for splints. If an artery is severed and the soldier’s life blood is rapidly spurting out he makes a compress of a stone and a piece of cloth, snatches up a belt or a rifle sling and twists it into place with a bayonet.

The result may not be a neat looking tourniquet, but it does the work. It stops the flow of blood.

Then he shows the man how to use a rifle for a crutch and helps him off to where a wheeled litter can pick him up. All this time he has been under fire and perhaps before he can begin work on another man he himself may need aid.

Source: Daily Kennebec journal. (Augusta, Me.), 09 May 1898.