Was Napoleon’s heart eaten by rats and replaced with a sheep’s heart? Or was it actually placed in a tureen and buried with him?

Throughout history, there have been many rumors about Napoleon’s heart and just what might have happened to it.

Below is a lengthy article published in 1915 on this very subject.

New Light on the Mystery of Napoleon’s Heart

The baffling and gruesome mystery concerning the great Napoleon’s heart seems at last to have been authoritatively settled.

For nearly a century reports have been prevalent in France and England that the heart was not buried with the body.

According to some versions it was “appropriated” by the Emperor’s physician, Dr. Antommarchi, or by some other Frenchman.

Other accounts say that it was devoured by rats during the funeral preparations and a sheep’s heart substituted for it.

This controversy had reached such a point that shortly before the present war [WWI] Dr. Raspail and Dr. Cabanes, both well known French physicians and writers, petitioned the French Government to have Napoleon’s tomb in the Invalides opened to decide the question.

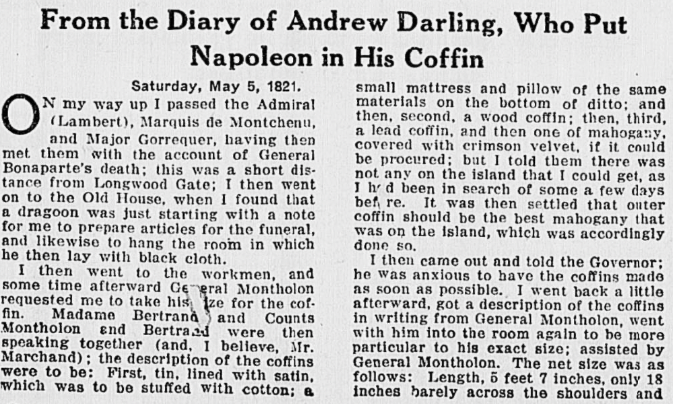

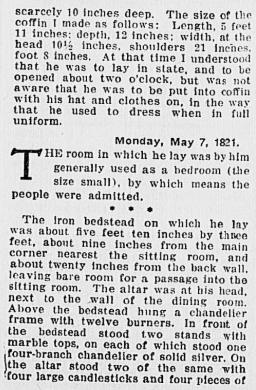

The discovery which appears to end the dispute has been made by Major F.M. Foulds, the medical officer now in charge of British troops at St. Helena. He has found the diary of Andrew Darling, an upholsterer, who had charge of various repairs and finally of the arrangements for Napoleon’s funeral at Longwood House, St. Helena, where the great Emperor died on May 5, 1821.

Darling describes with great detail how he helped to enclose the Emperor’s heart in a silver vase or tureen, which was then placed in the coffin. Darling, although somewhat illiterate, is evidently a very careful and conscientious man, and there is every reason to believe that his statements are absolutely reliable.

The precise details he gives go to prove this. He wrote with no idea of the controversy that would arise over Napoleon’s heart, and his diary was mislaid shortly after he wrote it in 1821, and has not been brought to light again until today.

A curious confirmation of the accuracy of Darling’s details has been furnished by Mrs. Owen, an aged lady of 95, who was a baby in St. Helena at the time of Napoleon’s death and is still living in London.

She was the daughter of Captain Bennett, of the British army and remembers hearing her family tell that they had sold a mahogany dinging table with a remarkably thick top to furnish wood for Napoleon’s coffin.

Darling, it will be noticed, speaks of the difficulty in finding mahogany on the island to furnish a coffin of that material.

It may still be argued that Darling’s diary does not prove that Napoleon’s heart was not stolen or destroyed and a sheep’s heart substituted for it.

Darling, of course, did not know that the heart he helped to seal up was really that of Napoleon and not that of a sheep. He did not think of such a matter.

Apparently the heart and stomach had been lying in separate receptacles since the previous day, and something might have happened to them. Nevertheless, considered in connection with the inherent improbabilities of the sheep’s heart story, Darling’s diary does make very convincing evidence.

He knew that Dr. Antommarchi wished to secure Napoleon’s heart and that some of the other Frenchmen wished it, and that the English authorities, who were in command, would not permit such a thing. It is not easy to go out and secure a sheep’s heart and substitute it for a dead man’s heart in charge of soldiers of a foreign nation.

The story of the substitution of the sheep’s heart is certainly curious and rests on several pieces of evidence. It is most strongly stated in the “Memoirs” of Dr. Charles Thomas Carswell, an English physician, who took part in the autopsy. He writes:

“Dr. Antommarchi, assisted by Dr. Charles Thomas Carswell, proceeded to the autopsy of Napoleon. Night overtook them. When the doctors came in the next morning they discovered that the heart of the Emperor had been eaten by rats. They replaced it by that of a sheep, which they had killed immediately.”

Dr. Carswell further states: “Through a board in the wall, as I entered, I could spy a rat just devouring the right ventricle.”

Some plausibility is given to the rat story by the fact that there was undoubtedly a plague of rats at St. Helena at the time of Napoleon’s death. The island was then an important calling point on the way to the East, the ships carried the rats there and the animals found conditions very favorable.

When Napoleon’s body was taken to Paris in 1840 it was exposed to public view for a short time, but there is no mention of the disposition of the heart.

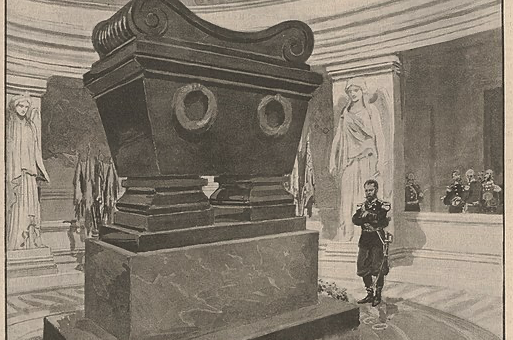

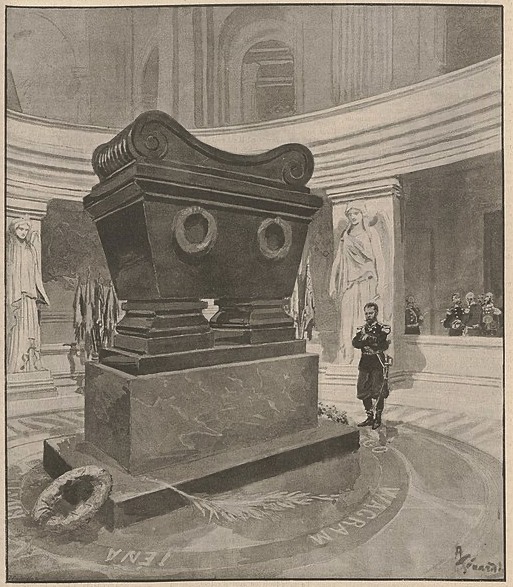

The original coffin in which the body was brought from St. Helena was preserved, and around this was placed a coffin of iron, one of steel, one of lead and one of ebony. Around this last is the great sarcophagus hewn out of a single block of Siberian porphyry, which now meets the visitor’s eye in the Chapel of the Invalides.

Source: Richmond times-dispatch. (Richmond, Va.), 31 Oct. 1915.