Did Homer’s heroes visit America long ago and share symbology and stories with the people in North and South America? That is the question inspiring the following article, first published in 1917.

Did Old Homer’s Heroes Visit America?

By Dr. W. H. Ballou

An American scholar, Harold Sellers Cotton, of the University of Pennsylvania, has seriously raised the suggestion that the ancient Greeks were in communication with ancient, pre-Columbian America. As his researches relate to the use in America of a symbol of the Cretan period of Greek civilization, they may lead to the conclusion that the heroes of the mysterious pre-historic Homeric age, which originated in Crete were early voyagers to America.

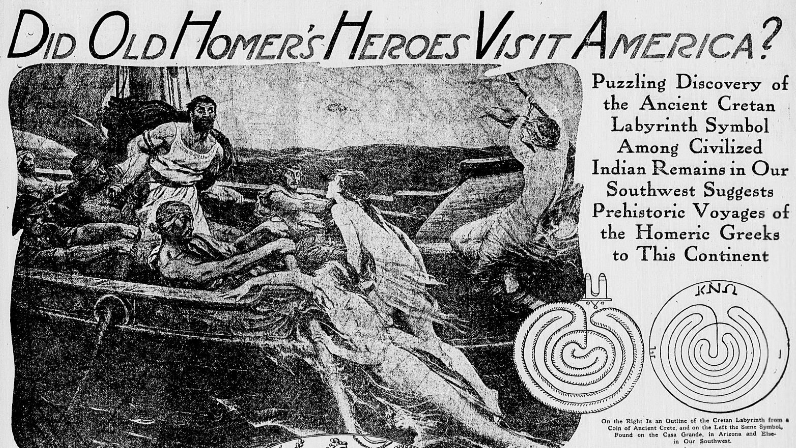

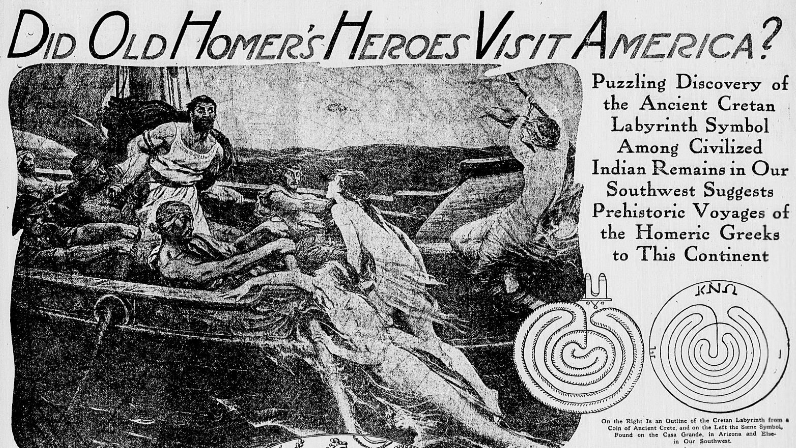

Professor Cotton has found striking evidence that the labyrinth designs associated with the horrible legendary Minotaur of the Minoan age of Crete has been familiar to our Southwestern Indians from the earliest times. The similarity between this labyrinth design on an ancient Cretan coin and on certain Indian relics of the Southwest is so perfect that it appears to exclude all possibility of accidental coincidence.

The Pennsylvania scholar was led to this discovery by an article in the American Anthropologist entitled “A Fictitious Ruin in the Gila Valley, Arizona,” by Dr. J. Walter Fewkes, the noted archaeologist, of the Smithsonian Institution. In this article Dr. Fewkes gave a picture of the labyrinth symbol as it had been first observed and copied by an eighteenth century Spaniard, scratched in the sand by a Pima Indian. The point of Dr. Fewkes’s article was that this symbol did not represent the plan of a ruin as previously supposed, but was used in some way as a game by the Indians called “the house of Teuhu” or “Teuhiki.”

It immediately occurred to Professor Cotton that he had seen the same diagram on the reverse of a silver coin of Knossos in Crete of the Greek period B.C. 200 to 67. The figure represented the Minoan Labyrinth and has been found on coins and in inscriptions in Crete back to the earliest period. A comparison of the Indian symbol with that on the coin showed that they were identical in every respect. As the Cretan design represents a maze, out of which it was exceedingly difficult for a person to find his way, it is necessarily a complicated figure. It is unquestionably very astonishing that this Cretan design should be found in early American Indian records, duplicated down to every line, every intricate curve and every opening.

In the Indian figure, as is shown in accompanying diagrams, there is, entirely separate from the labyrinth, a little addition which does not appear on the Greek coin. This addition is a small drawing of two upright pillars. It may not be without significance that these two pillars, forming part of some kind of altar, also occur frequently in early Cretan inscriptions.

Dr. Fewkes points out that the symbol was early known to the Pima Indians, as the diagram, in slightly modified form, appears scratched on the adobe wall of the ancient Casa Grande ruin among Indian pictographs. Therefore, it seems certain that it exists among the pre-Columbian Indians and could not have been introduced by the Spanish discoverers or by the old Spanish traveller in his manuscript.

We are therefore forced to one of these three conclusions: 1. That the symbol originated in Europe and was carried to America in prehistoric times. 2. That it was carried from America in prehistoric times. 3. That is arose independently in prehistoric times.

While it is frequently accepted by American authorities that such simple forms as the Cross, the Swastika and the Wall of Troy design may have originated independently in the New World as well as the Old, it is hard to believe that such complicated labyrinths, similar in every detail, could have had separate origins. Similar environments often call forth similar responses in different organisms. In such cases the similarities when careful analyzed are found to be superficial. The details will not agree. In the case of the two labyrinths, however, the agreement is exact.

The history of the picture reproduced by Dr. Fewkes does not prove beyond question that it is of genuine American Indian design, but there are many facts which confirm its authenticity. An unknown Spanish traveller visited the Pima country in the year 1761 and left an account of his visit in the form of a manuscript. On the margin of one of the pages of this manuscript appears the picture of the symbol.

According to the Spanish writer, the Pima drew the picture in the sand. He stated that “it represents a house of amusement rather than that of a magnate.” As Dr. Fewkes had never heard of a ruin with such a ground plan he was led to question an old Pima Indian known as “Higgins” about it.

When Higgins was shown the figure and told the opening lines of the quotation from the Spanish narrative, the statement about the uses of the house being withheld, he answered that he knew of no ancient house in that region which had a ground plan like that indicated in the figure. He was, however, acquainted with a children’s game that employed a similar figure traced in the sand. The Pima, he said, call the figure “Tchuhuki,” meaning “the house of Tcuhu,” a cultus hero sometimes identifies with Montezuma.

But how are we to explain the apparent connection between ancient Cretan civilization and out formerly civilized American Indians? The prehistoric ruins of our Southwest, of Mexico, Central America and South America are continually proving the antiquity of civilization on this continent. It has recently been shown, for instance that at Mesa Verde we have a sun temple older than Stonehenge.

On the other hand, recent discoveries in Europe have traced the origins of ancient Greek civilization to the Island of Crete, and it was in Crete that the famous labyrinth of King Minos, whose reproduction has just been found among early American antiquities, existed.

In Crete, too, was the Cave of Dicte, revered in the earliest times as the birthplace of Zeus, the father of all the Greek gods. The actual altar which commemorated the god’s birth in this cave is one of the many wonderful discoveries which have been made in recent years by Professors Hogarth and Evans, the English archaeologists.

In Crete arose the Homeric civilization of Greece, which was entirely distinct from that of the Greek historical period, the age of Socrates and Pericles and the other famous Greeks, who are usually spoken of as representative of Greek civilization. There is a great dark blank between the historic period and the age described by Homer. The civilization of the earlier period was entirely different from the later, simpler in some ways and yet superior in others.

To this earlier period belonged the story of Paris and Helen, the siege of Troy, the anger of Achilles, the valor of Hector, the deeds of Ajax and Agamemnon, the love of Andromache, the wanderings of much enduring Ulysses, and the trials of his faithful wife Penelope. It was an age in which kings appear to have tilled their own fields and lived in a patriarchal manner. It showed its superiority by the freedom and comparative equality accorded to women, as compared with their position of restraint and seclusion in the Greek historic period.

Archaeological research has shown that this early civilization spread from Crete to the Greek mainland, and that it built the great cities of Mycenae and Tiryns, which have been unearthed in modern times.

On the Island of Crete civilization reached its height under the Minoan kings. The island occupied the greatest strategic position in the Mediterranean and its ships traded to all parts of the civilized world, perhaps even to America, using the calm route across the Atlantic by way of Gibraltar and the West Indies. Remains of the great docks and harbor works existing in Crete in the Minoan age have been found recently.

The Greeks of the Homeric and the Minoan period were evidently great sailors. They were much more devoted to the sea than the Greeks of the classical period. This is proved by Homer’s story of the wanderings of Ulysses in “The Odyssey,” the first great sea story.

Such facts have an evident bearing on the possibility of early communication between the Greeks and America. In the present state of our knowledge it is more reasonable to believe that the highly intelligent and enterprising Greeks went to America rather than that the pre-Columbian Americans cruised to the Mediterranean. With vessels like that of Ulysses it would have been quite practical to travel to American by the calm tropical belt.

Then we must remember the vast mass of ancient legends concerning a lost continent called Atlantis, which extended a great distance westward into the Atlantic Ocean. Many scholars believe that this was really Crete, while others have argued that it was Northern Africa, which approaches much nearer America than any part of Europe.

King Minos, the founder of the Minoan dynasty, was, according to fable, the father of the monstrous Minotaur, the man-headed bull. The monster was kept in a labyrinth in the royal palace and every year the Athenians were compelled to send seven maidens and seven youth as a tribute to the monster.

One of the most beautiful of ancient Greek legends tells us how the splendid Athenian youth Theseus, with the help of Ariadne, daughter of King Minos, slew the Minotaur and found his way out of the Labyrinth, thus saving his countrymen from the cruel tribute to which they had been subjected.

This fable must be regarded as an echo of the subjection in which the Minoan kings kept some of the people of the mainland. It is certain, however, that pictures of bulls and of boys and girls fighting bulls constantly occur among the decorations of the buildings of the Minoan period, and it is supposed that Athenian captives may have been forced to sacrifice their lives in this sport. An actual labyrinth has also been found at Knossos.

The labyrinth, like other constructions of King Minos’s civilization, is reputed to have been the work of Daedalus, the inventor of the first flying machine. From that early period the curious design of the labyrinth was the usual symbol of Crete and continued to be so until comparatively late in historic Greek times.

Now we are confronted with the strange fact that primitive Americans also used this curious symbol.

Source: Richmond times-dispatch. (Richmond, Va.), 05 Aug. 1917.