According to the Code of Hammurabi, a set of laws written in 1754 BC:

“If a man charges another with black magic and has not made his case good, the one who is thus taxed shall go to the river and plunge into the water. If the river overcometh him, then shall his accuser possess his property. If, however, the river prove him innocent and he be not drowned, his accuser shall surely be put to death, and the dead man’s property shall become the portion of him who underwent the ordeal.”

Over the centuries, the ordeal by water was used off and on to prove or disprove a person’s innocence.

Also referred to as the swimming test, trial by water became a popular method of uncovering witchcraft during the 16th to 18th centuries.

The belief was that if the accused witch sank deep into the water, she was innocent. If the accused witch floated or bobbed along the surface of the water, she was found guilty and executed.

While the accused witch usually had a rope tied around her waist to pull her out of the water if she sank, there were many instanced where the accused was drowned.

Many believed that water, being pure, would repel the wicked, hence the reason why witches could not drown. Some believed that since a witch had turned to the devil, the sacred baptismal waters would automatically reject her impureness.

According to King James:

“So it appears that God hath appointed, for a supernatural sign of the monstrous impiety of the witches, that the water shall refuse to receive them in her bosom, that have shaken off them the sacred water of baptism and willfully refused the benefit thereof.”

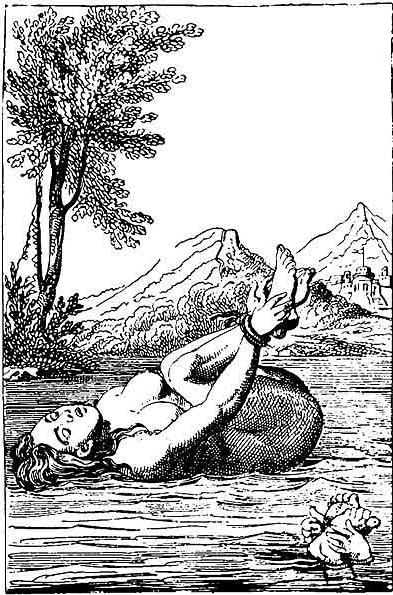

Before being dunked into a body of water, the accused was tied with a rope. A description of how the accused might be tied in 1653, said that the right thumb was tied to the left big toe. Some period illustrations show the accused with his hands and feet tied together. In one illustration, the woman about to be tried was tied into a sack. The accused was then dunked into the water up to three times to see if she sank or floated.

Of course, there were methods for ensuring that the accused would float. These methods were written about in the 1600s, and the only reason why the accused was allowed to float was so that she or he could be tortured and executed.

By the early 1700s, trial by water was falling out of favor. In 1712, Lord Chief Justice of England, Thomas Parker, declared “that if any dare for the future to make use of that experiment, and the party lose her life by it, all they that are the cause of it are guilty of willful murder.”

In spite of the law, superstitious mobs in Europe continued to practice ordeal by water on the poor and elderly until the 19th century.