From January 1918 to December 1920, it is estimated that the Spanish Flu infected about 500 million people worldwide and ended the lives of 50 million men, women, and children. 675,000 of those deaths were in the U.S.

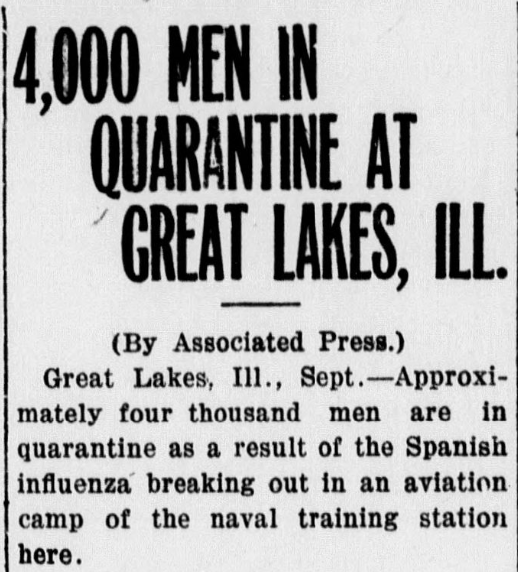

During this time period, quarantines were enacted in different parts of the United States.

One of the earliest mentions I found for a U.S. quarantine was in a Vermont newspaper article published on September 14, 1918. The article, pondering the origin of the Spanish flu, stated that:

“Spanish influenza, which recently ravaged the German army and later spread into France and England, has been brought to some of the American Atlantic coast cities, officials here fear, but they are awaiting further investigation and developments before forming definite opinions.

“The strange infection is thought to have been brought over by persons on returning American transports. There is little means of combatting the disease except by absolute quarantine.” [1]

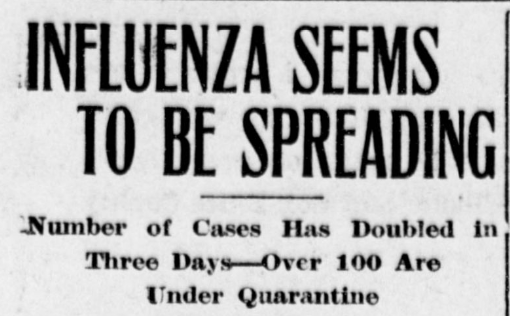

The day before this article was published, Long Island’s Camp Upton, had 38 flu admissions. On the second day there were 86 admissions and on the third day there were 193 hospital admissions. On October 4th, admissions peaked at 483 and within 40 days since the start of this flu, a total of 6,131 men from Camp Upton had been hospitalized. [2]

By October 10th, the Spanish flu hit Washburn, Wisconsin with over fifty cases. The city’s health department announced that all schools, churches, theaters, and all other public places were to be closed until further notice. No children were allowed to leave their homes under the quarantine.

Fourteen days later, the Spanish flu had claimed seven lives in Washburn. A local newspaper reported that:

“In most cases those who died contracted pneumonia following the influenza and death resulted within a few days. The disease has been no respecter of persons, claiming old and young alike.

“The quarantine which was put upon the city more than a week ago by the local health board is still being maintained and will not be raised until there is a lessening of the number of cases.

“Because of the large number afflicted the doctors of the city have been kept on the jump caring for the sick and many new cases are appearing daily.

“The Health Officers of the city are doing all in their power to prevent the spread of the disease but without proper support they are handicapped.

“Individuals can assist by avoiding crowds, keeping the body healthy and when ill call a doctor and follow his advice.” [3]

One day later, on October 25th, Hawaii announced that anyone with the Spanish flu must go into quarantine. Honolulu was getting hit hard with flu cases.

In early November, it was being reported that parts of Alaska were being quarantined.

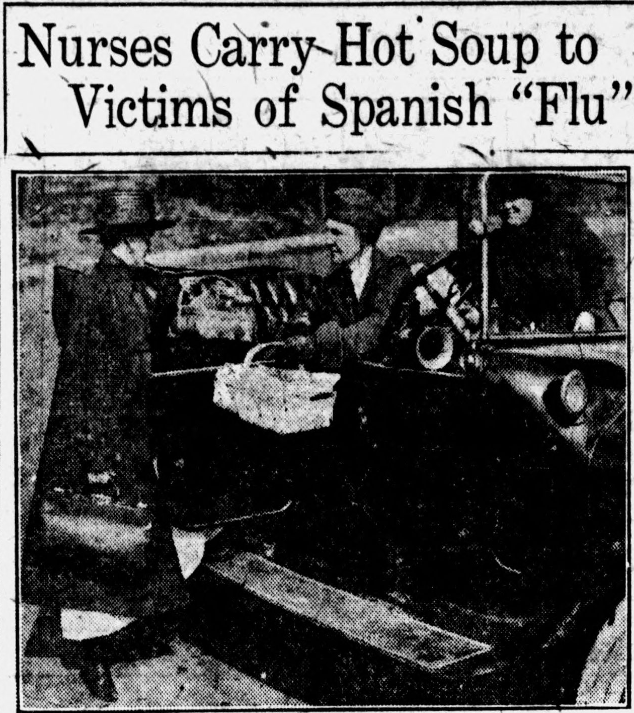

With the Spanish flu having invaded all corners of the U.S., health and government officials tried to figure out what more they could do to prevent the spread of the flu.

In Oregon, November 7, 1918, it was announced that quarantines must put up a white flag. The announcement stated that:

“The Pendleton city council last evening voted for a more strict enforcing of quarantine regulation of Spanish influenza cases. All places where the disease is known to exist are to be required to display a white flag. This will be a notice to the public where the cases are.” [4]

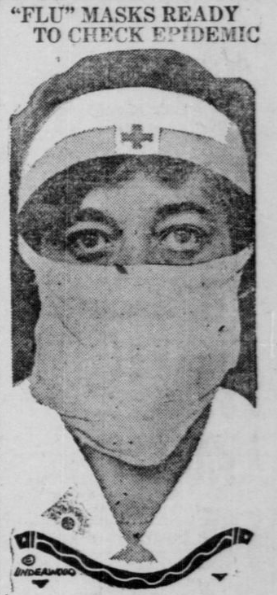

Meanwhile, the men at Camp Kearny, located in San Diego, were growing restless under quarantine. On November 10th, officers were given permission to leave camp and go anywhere within 20 miles of the camp as long as they wore face masks.

By the time the Christmas season rolled around in 1918, people were instructed to celebrate the holiday quietly at home.

By February of 1919, people were itching to get on with their lives and many places were dropping their quarantines only to have to reinstate those same quarantines by October and November of that year.

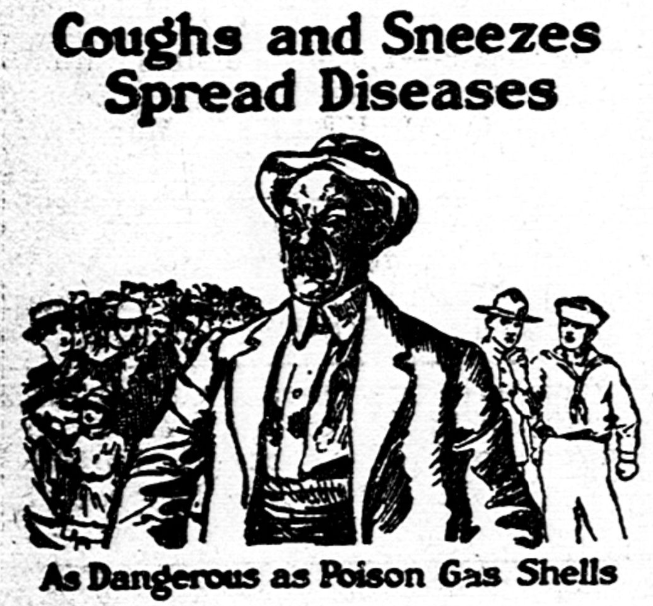

The public was also instructed to wear gauze masks when visiting the sick and in public. Those who were sick and those who were in recovery were instructed to hang their clothing out in the sun for eight hours and to air out their homes for the same amount of time.

In spite of all the deaths that occurred, people were still congregating and spreading the virus.

By 1920, quarantines were still being upheld, reinstated, and put in place for the first time in some area.

In January, 1920, Iowa’s State Board of Health were hanging flu signs on all the houses where the flu was active.

A month later, in Nebraska, it was being reported that Spanish influenza cases were once again increasing. However, unlike the previous two years, the Spanish flu seemed to be weaker and fewer people were dying from it.