The following report, originally published in 1934, details the beliefs in magic during that time period in Mexico.

While the article sometimes reminds readers to dismiss such “nonsense,” the information itself is well worth the read.

If you are only looking for superstitions, scroll down to “Superstitious Beliefs.”

Weird “Black Magic” Below the Rio Grand

Mexico City, August 4, 1934 — That “black magic” practices still flourish at places in Mexico is revealed by recent investigations of superstitious customs in this country.

These practices are not confined to any particular area in Mexico. Like many of the pre-conquest native rites of which they are often offshoots, the dealings in mysterious charms for every conceivable purpose are to be encountered in almost any section of the country, not excluding the capital itself.

True enough such practices are to be found among the poorer strata of the population; but as in Cuba, where voodooism has a firm hold and a long tradition, the Mexican middle classes are not without their “believers” in the efficacy of these obscure incantations which as often purpose to cure as they do to kill.

In many of the smaller villages where witchcraft has a greater number of followers, the witches and medicine men often have their own residence wards – which are not exempt from class divisions, since witches and medicine men in Mexico frequently fall into the category of first class, second class or third class, according to the extent of their occult powers.

Although a great deal is also heard in Mexico about strange “pacts with the devil,” the real base of these practices in this country is to be found in a certain knowledge of herbs, some quite mild and used to heal minor ills, others very powerful and used for more serious purposes as to kill or drive mad.

Widespread Use

The widespread prevalence of such practices in the villages has given rise to innumerable arrests on charges of murder, theft and other crimes. The accused are rarely found guilty, owing to the difficulty of obtaining absolute proofs and to the authorities’ fear of arousing the ire of the brujas and brujos, as the witches and medicine men are called in Mexico.

Wrong Information

Yet, some authorities have dared to challenge the power of these feared beings. There is a story told of a case in a village near Mexico City where a witch persuaded a client that the client’s physical ills came because he was being bewitched by his own wife.

For months he allowed himself to be treated by the witch, but to no avail. Finally, the witch suggested to the poor man that he consult one Don Ambrosio, who also indulged in magic spells and incantations, and that his “power” might be stronger than hers. No sooner said than done. Don Ambrosio’s “analysis” was to the effect that the man’s fever, stomach pains and general physical debility were owing to the fact that his wife had cast a spell on him because she hated him.

Meanwhile, his wife was consulting another witch, by the name of Bartola, for the purpose of curing her husband and bringing him back to her as the loving husband he had once been, since she loved him.

When the husband returned home he was furious over the second brujos confirmation of what the first had told him – namely, that his wife had cast a spell on him. He gave her a terrible beating and she had him brought up before the village mayor, who questioned the unhappy couple and got the whole story.

Then the two brujos were brought in. A doctor was called to examine the husband, whom he found to be suffering from a severe case of malaria, and his daily fevers were simply owing to this fact rather than to the “spell” which his wife had allegedly cast upon him.

The two brujos were put in jail, and the married couple was reunited. The peasants of the district predicted a tragic ending for the mayor, who had dared to challenge the power of the witches and medicine men. It was rumored that all the brujos of the village gathered together nightly in isolated spots to cast an evil spell over the mayor.

But apparently the mayor was immune to their powers, and eventually the entire ward of witches and medicine men left town.

Autosuggestion

The above incident has a quite prosaic ending, but there are numerous similar cases reported all over the country which wind up in horrible tragedies, owing to the protagonists’ unshakable belief in the witches and their deep-rooted fear of the inhuman power wielded by them.

Pronounced autosuggestion in innumerable cases leads to absolute madness, murder, suicide and chronic ailments. Yet, “black magic,” as practiced in Mexico, is difficult to combat, since often no very elaborate ritual is needed to achieve the desired result.

It is sufficient for so-and-so to be told quite casually that his former sweetheart is having an evil spell cast over him with the aid of his photograph, which he had given her during their idyllic days, for the terrible cycle of autosuggestion and attempts a counter bewitchment, with the aid of other brujos, to begin.

Thenceforward, every little pain suffered by the supposed victim is attributed to the spell which his former sweetheart is weaving around him.

He is convinced that she has had a cloth figure in the form of a human body made, with the victim’s photograph fulfilling the role of the face, and that after the necessary magic words have been intoned, pins are stuck into various parts of the figure. Hence his pains, which grow more terrible each day!

His only remedy, so he has been told by his friends and his parents and his parents’ parents, is to counteract the spell and have the woman bewitched. Then the same process of relentless autosuggestion begins to take hold of the girl, his alleged tormentor.

Superstitious Beliefs

It is a cruel cycle, the product of centuries of superstitious belief, and frequently it ends in the death or severe mental derangement of one or all the protagonists.

In some villages almost every minor occurrence slightly out of the ordinary run of things is attributed to the witches and evil spirits.

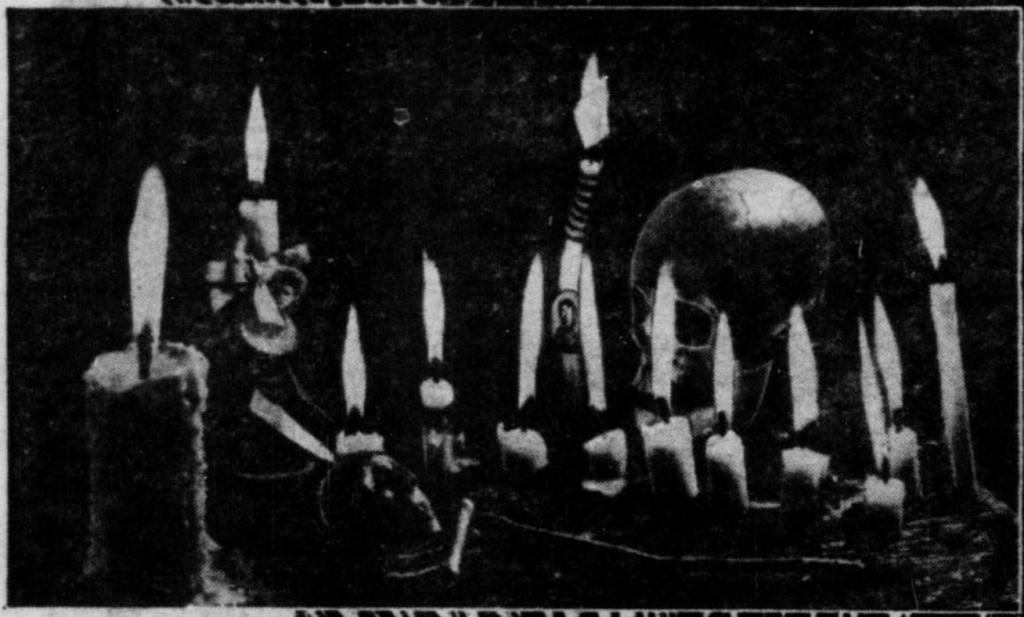

If a child wakes one morning with a swelling or two on his limbs, he has been “bloodsucked” by the witches, and the family scissors must be arranged in the form of a cross and placed near the door to keep the witches out!

Did the late traveler report having seen some balls of fire dancing near the cemetery? They were witches hunting for fresh corpses!

If thieves are rumored to be about, it is necessary to find a skull and bury it beneath the front door to keep them away!

If a candle is wrapped in red silk, the prodigal lover will return, “bringing his surrounding love anew.”

If a pin is stuck in the heart of the beloved one’s photograph, he or she is sure to remain faithful and constant.

No End in Sight

And the list of age-old beliefs which are the main prop and support of witchcraft is an endless one, ranging in classification from how to recover a lost puppy to the most efficient occult means of poisoning one’s worst enemy.

Superstitious practices in Mexico probably reached their acme during the Spanish Colonial times, in the very shadow of the church which was intent on transforming every trace of the natives’ pagan beliefs into Christian thought and feelings. Measures of “adaptation” of many of these beliefs and practices to bring them into the church’s fold were frequently followed by the friars in their catechization of the Indian masses.

A number of these adaptations, which would hardly be called legitimate today, explain the fact that even today the native dances which are celebrated in innumerable Mexican villages on the occasion of the celebration of church holidays, reveal unmistakable features of the old pagan beliefs.

The famous shrine of Guadalupe, situated about a mile and a half from Mexico City, which is visited annually by hundreds of thousands of natives supposedly in devotion to the sacredness of the miracle alleged to have taken place there in the time of Mexico’s first archbishop, Zumarraga, is the site of the old Aztec temple consecrated to Tonantzin, the pagan goddess of corn and fertility.

Even today in villages one comes across little printed prayers similar to those which abounded in Colonial times and which are supposed to keep the bearer of them immune from all ill, from the legal authorities as well as from private enemies, from plagues, from discord with one’s wife, at the same time assuring the wearer that 40 hours before his death, should he hang the prayer cord suspended around his neck, a vision of God himself will be granted him.

In Colonial times these prayers (which sometimes bore unique proofs of their efficacy, such as how even a dog around whose neck one of the prayers had been hung had proved itself to be immune from death after knife blades had traversed its body) were often endorsed by viceroyal and ecclesiastical authorities. Their selling price has varied little since then – from 5 to 20 centavo per prayer.

Upon their arrival in Mexico the Spanish church authorities were confronted by a highly intricate system of native rite, “magic,” and musical festivals, the latter often related to the Indians’ religious beliefs and ceremonies. Not only did the conquest not do away with these rites entirely, but the people’s essential faith in the general efficacy of magic – “black” and otherwise – has never been seriously shaken.

Source: Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 12 Aug. 1934.