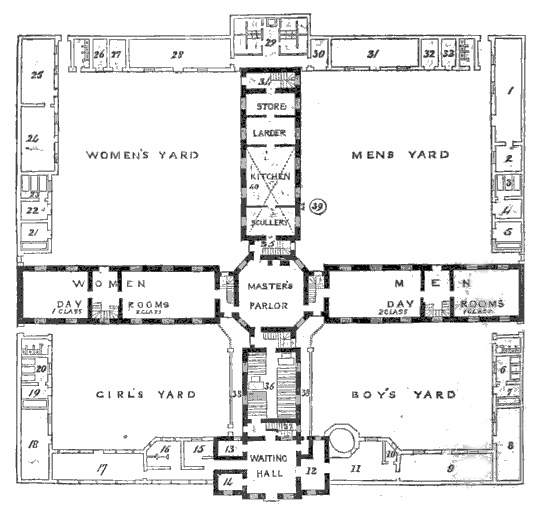

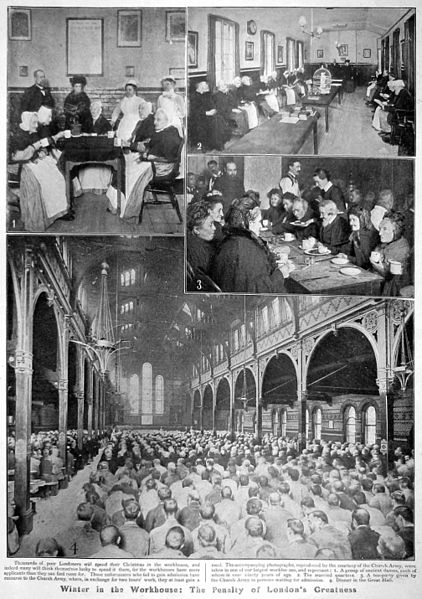

Workhouses were where the poor went to receive food and a roof over their heads when times were at their absolute worst. In exchange for the very basic necessities, the paupers were put to work, often working up to twelve hours a day. The profit that was earned from their work was then given to the guardians of the workhouses who could spend the money as they pleased. This led to a wide variety of conditions within the workhouses.

There were some decent workhouses in the 1800s and early 1900s, but the vast majority of them were considered death traps. It all depended on whether the house guardians provided for the inmates with the profits or if they cut their expenses and treated the inmates like trash.

Regardless of the conditions, many people had no other choice than to submit to the workhouses. Many people died within their walls, some went on to live their entire lives within the system, and a few managed to find work on the outside. Each person had a story to tell and every experience within the workhouses was a personal one.

Dangerously Overcrowded And Dirty

An Inspector found the Preston Workhouse, Lancashire, England “dangerously crowded” in 1867. On his visit he discovered the sick and diseased sharing beds and in one of the wards set aside for men with skin diseases, six men shared two beds. The entire place was infested with every sort of bug imaginable which were, no doubt, snacking on the inmates as they slept in filth.

At another workhouse located in Barnsley, an inmate was discovered in bed without adequate clothing and covered in vermin. The poor man was suffering from a broken and dislocated hip he received when a local coal mine exploded. When the Inspector spoke to him about his condition, the injured man said that the doctor in the workhouse did not want to be disturbed and that he must suffer through the injury. Only one nurse bothered to care for the man, as well as the other patients placed in the workhouse infirmary, and this nurse never bathed any of the patients.

In yet a different workhouse, the infirmary was located in a horse stable. The food was cooked in the same pots they used to boil soiled linens. [SOURCE 1]

Workhouse Puddings

The suet pudding served for breakfast every day at many workhouses in England hit the spotlight in 1896. An inmate’s complaint was published in a newspaper, letting the public know that the pudding was so heavy with suet that many inmates were incapable of eating the stuff. In fact, many of the elderly workers had to skip out on eating breakfast at half past six in the morning and did not get another morsel to eat until six in the evening.

By 1898 the issue of the workhouse pudding was being addressed in a most backwards manner. The amount of suet was being reduced and skimmed milk was being used in the pudding. However, the government wanted to follow their dietary table, giving the pudding a texture similar to “pieces of liver.”

Eventually it was decided that the pudding could be made “in accordance with the wishes of the guardians.” [SOURCES 2, 3]

A Matter Of Taste

There were numerous cases of workhouse inmates refusing to eat what was given to them, and because they would not eat, they could not work due to starvation.

In 1901, a group of women at the Bradford Workhouse decided to strike because of a change made to the menu. The government decided to do away with tea and serve the inmates gruel, instead.

The gruel was made with “three ounces of oatmeal, a pint of water, half an ounce of treacle, and salt to taste.” When it was served, the women rose in unison and left the room. They refused to work without their cup of tea and were accused of being rowdy.

It was soon discovered that three of the women were the ringleaders to the strike and they were brought to stand before the stipendiary. For their defiance, they were sent to prison for a week.

There was another case of inmates refusing sustenance at the Rockdale Workhouse in 1905. That time, the women were served steamed cod, but as one woman described it, it was “like eating paper shavings boiled.” Over a hundred of the inmates refused to eat the fish and the guardians of the house launched an investigation. It was soon discovered “that the steam used for the first cooking came from a boiler which had been treated for corrosion.” The fish had traces of sulphide of iron, giving it an inedible taste and texture. The guardians rectified the situation by giving the inmates freshly baked cod. [SOURCES 4, 5]

She Wanted To Take Away The Christmas Beer

“Christmas without beer in an English workhouse would be like a Fourth of July without firecrackers,” said a London report published in 1922. For many people in the English workhouses, Christmas was the only time they could have a cup of cheer, but, of course, there was always at least one person who was against any sort of happiness for the less fortunate.

Mrs. Edith Day, a member of the workhouse trustees wanted desperately to take away the Christmas beer from the inmates of the Bishop Stortford Workhouse. For twenty-nine years she had petitioned to have it removed, but thankfully did not succeed. Her tactics were likened to the American prohibitionists and she believed it was “wrong to spend the taxpayers’ money on strong drink. If a man or a woman can go without beer every day but one in the year there is no need for them to upset themselves just because it is Christmas.”

Not all workhouses were alike on the issue of alcohol. For example, in 1925 it was reported that the men of the Omagh Workhouse in Ireland were allowed three glasses of whisky a day. [SOURCES 6, 7]

It Could Happen To Anyone

While some people would like to think that the poor deserved to be mistreated, one has to realize that many of the people who wound up in the workhouse had previous jobs or may have once been a person of great influence.

A newspaper report from 1925 told readers how a once famous billiards champion ended up in poverty. William Cook had a great income, broke the world’s record in billiards, and taught the sport to people in high positions. Life was good until his health took a turn for the worse and he ended up working in the laundry room at the Marylebone Workhouse.

In 1887, there was a report that a gentleman had died in the Eltham Workhouse. The man lived for two years in the workhouse under an assumed name and the employees of the workhouse did not know his true identity, but they did know that the man was fluent in French, German, and Hindustani. He also knew some Latin and Greek. He had served in India as an officer and later lost money in the mines.

This unknown man was struck with paralysis and returned to England to exist in the workhouse. Upon his death, the mark of an earl’s coronet was found on some of his linen, but his true identity was not released. [SOURCES 8, 9]

Museum Of The Forgotten

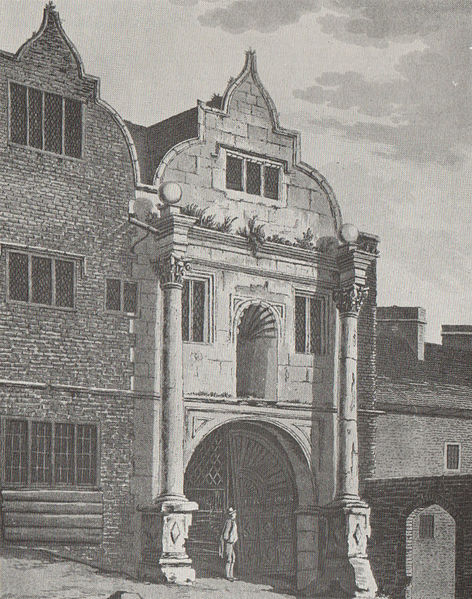

While there are many workhouse museums across the world today that provide the history of individual workhouses, there were, in their time of operation, living museums attached to the workhouses.

As the poor and destitute entered the workhouses, they often passed away leaving odd trinkets, papers, and other objects behind. These items, now the property of the workhouses, were placed on display in a room called the museum.

Many war and military service medals were left behind as well as good luck stones and talismans with no real monetary value. One such talisman, displayed in a South London workhouse museum, was a coin with a hole bored through it. Engraved on the coin was, “Given to me by Cecil Rhodes,” who was a British businessman and a South African politician.

There were plenty of knives. Some had histories, but most did not.

Papers were also kept in the museum and included poetry, book manuscripts, and even a written confession of murder. A South London workhouse also had an order of knighthood that was left behind by the son of the person knighted.

Wedding rings and marriage certificates filled the room, forcing the living to look back at the unfortunates who passed before them. [SOURCE 10]

Oakum Picking

Oakum picking was a typical rough job given to prisoners and workhouse inmates in the 1800s. It involved taking old rope and untwisting it, breaking it down to its fibers. These hemp fibers, mixed with tar, were then used to caulk the seams in wooden boats.

It may sound simple enough, but the job was tedious and left workers with blisters and permanent scarring on their hands.

One woman who had volunteered herself to briefly experience life in a workhouse talked about oakum picking in an article published in 1892.

On her first day inside the English workhouse, a guardian came to her cell and woke her up at six in the morning. The inmate was given a can of porridge and some bread. She was given a few minutes to eat before the guardian brought her a basket of old rope and instructed her to fluff and separate it. She was also told that she would not be let out of her cell that day, even though she was not a criminal.

The inmate went to work in her cell, beating the rope against her metal bed frame to loosen the strands before untwisting them with her fingers. After several hours of working the rope, her fingers were blistered and bleeding. Her shoulders ached.

By nightfall, she was still working and in near tears. She asked the guardian how others could handle such tedious work for hours on end, day after day, and she was told that many of those who ended in the workhouse were uneducated and accustomed to the work. [SOURCES 11, 12]

The Smoking Irish Bride

Johanna Wood, age 49, married her 62-year-old husband right before Christmas in 1912. They were both inmates at a workhouse in Kent, where they met and fell in love.

However, Johanna had a bad habit. She liked to smoke tobacco in her clay pipe. It was observed that smoking tobacco was “her greatest source of pleasure” and Johanna admitted that she had smoked tobacco since she was a little girl.

Shortly after her marriage she was told that she could no longer smoke her clay pipe in the workhouse. When pressed with the decision of either giving up her pipe or living on the streets, she and her husband left the workhouse on New Year’s Day.

Some workhouses did allow tobacco smoking and in one instance a man bequeathed money in 1912 to the Carnarvon Workhouse to supply the inmates with the comfort of tobacco. [SOURCES 13, 14]

The Workhouse Or Death

Entering a workhouse after many years of gainful employment represented the loss of freedom and respectability. Instead of facing the shame, many people opted to kill themselves.

In 1896, a shoemaker, at the age of 76 years, was getting fewer and fewer jobs due to the loss of his eyesight and manual dexterity. It finally reached the point where he could not pay the coming month’s rent. His landlord said that he was faced with the choice of either death or going to the workhouse. The old shoemaker chose death and drank a large quantity of oxalic acid to end his life.

There were also cases of women dying of starvation outdoors with their frozen infants held in their arms. Men, mad with hunger, would kill themselves and their families rather than face the workhouses where their loved ones would be taken from them and their children given out to strangers. [SOURCES 15, 16]

Cold Needle Spray Bath

A form of punishment used in some of the Irish workhouses caused quite a stir in the newspapers in 1908. Apparently some workhouse guardians in Northern Ireland used the “cold needle spray bath” as both a punishment and a deterrent on the poor people within their hold.

The pauper would be stripped and imprisoned in the shower. The workhouse porter would then turn on “500 jets simultaneously from an elaborate series of perforated brass pipes for the space of two minutes.”

The matter was brought before the Irish Local Government Board who said that the punishment was unauthorized and could cause serious injury. A guardian at the meeting, however, stated that it was only “used as a deterrent for tramps” and that it had reduced his weekly casual inmates from 80 to 10.

This convinced the Board that it might not be a bad idea to use the water torture on the poor, as if somehow it would compel people not to be poor anymore, and they adopted a resolution that allowed the use of cold needle spray baths, but refused the allowance of hot water during the torture sessions. [SOURCE 17]