Polio is caused by a highly contagious virus. It is transmitted from one person to another through the environment. The fecal matter from one infected person can infect numerous other people through contaminated water and poor hygiene. Of course, none of this was known in the early 1900s when polio was infecting thousands of people each year in industrial countries. During this time of research and discovery, many beliefs surfaced as to the cause and cure of polio, most of which were either wrong or only half right. [SOURCES 1, 2]

The Baby Plague

Before it was called polio, the highly infectious viral disease was commonly called infant or infantile paralysis in the early 1900s because it affected so many infants and young children. It was also called the baby plague, even when it attacked adults. Infant paralysis eventually came to be known as polio. It is short for poliomyelitis and means “gray marrow inflammation.”

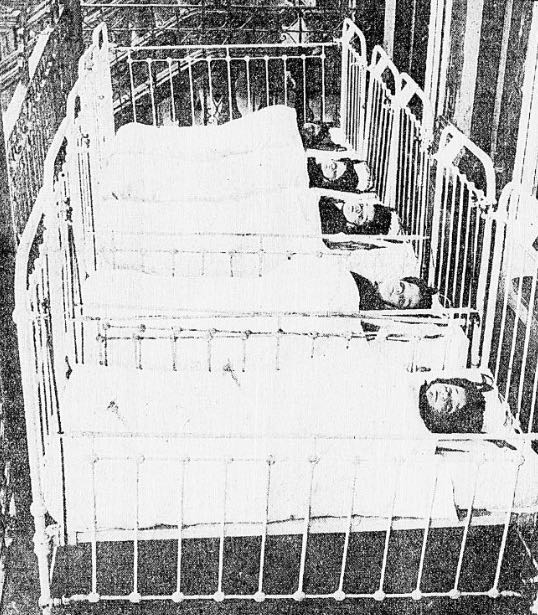

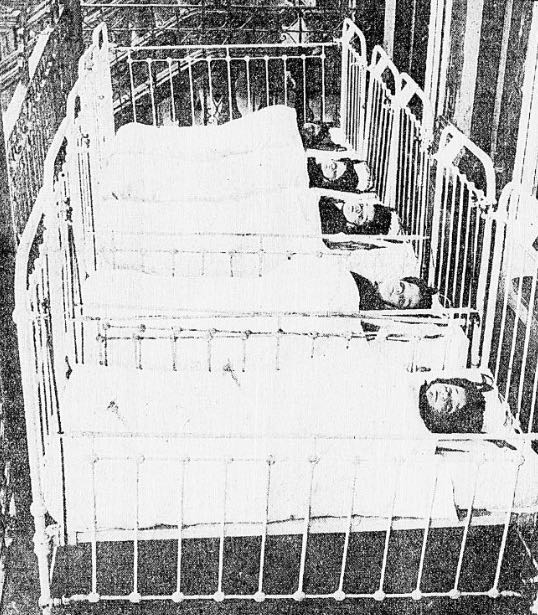

It was a frightening disease that could strike anywhere. In Chicago, summer of 1916, the county hospital was getting about 3 cases of polio a day. These unfortunate victims were being smartly quarantined even though the cause of polio at that time was not known. [SOURCES 3, 4]

It Closed Sunday School

Towards the end of the summer in 1910, severe outbreaks of polio closed down five different Sunday schools in Middleton, Connecticut. Six diagnosed cases occurred in Middleton within two days, causing widespread panic. Two high school girls died from the disease, making the high school consider closing its doors. In the end, the school decided against shutting down so as not to increase panic among the community.

The doctors were desperately trying to figure out what was causing the outbreak in their area. It was learned that students at the school shared a common towel and drinking cup. In spite of the unsanitary practice, no mention was made of stopping this practice of swapping germs among students who washed their hands or needed a drink. Some parents, in turn, decided to withdraw their kids from school. [SOURCE 5]

They Blamed It On Chickens And Pets

In 1910, newspaper articles questioned whether or not chickens were responsible for the polio outbreaks. The conclusion that chickens carried the disease came from a report of a chicken owner who, while caring for sick chickens, came down with polio. It was also being noted that chickens were dying of a “similar” disease according to other people who raised chickens.

The same was said about household pets. With the outbreak of polio, people started to report that their pets, cats and dogs, were coming down with polio before passing the disease onto other members of the family.

Surgeons and doctors examined the chicken remains and concluded that there was no evidence to link the illnesses between humans and chickens together. They were two, separate outbreaks.

It was not yet known that polio is transmitted from person to person. [SOURCE 5]

The Fly And The Rat

Desperately trying to find out how polio was spread, a Professor M. J. Rosenau announced in 1912 that he believed that the polio virus was transmitted from person to person by the stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans). The professor had “succeeded in transmitting infant paralysis from monkey to monkey through the agency of a biting stable-fly.” It doesn’t explain how people, not exposed to stable flies, got the disease, but the newspapers were excited by the news.

By 1939, the rat was being blamed for the spread of polio. The U.S. Surgeon General announced that rats may be infecting humans with the virus, but this accusation quickly died down after one doctor pointed out that rats were not known to be “susceptible to poliomyelitis.” [SOURCES 6, 7]

A Dirt Disease

By 1914, infant paralysis was being labeled a “dirt disease.” A newspaper published in Brisbane declared that parents were at fault for the spread of the virus. Governments and doctors were off the hook for the cause of the disease because “physical uncleanliness, external and internal, is the principal cause of the disorder.”

Parents were openly shamed for not bathing their children regularly, for keeping a disorderly home, and for feeding their children “food that they cannot possibly digest.” Failure to teach children proper manners was also at fault.

At this time, it was not known that contaminated public drinking water and outdoor bodies of water were a major source of the problem. Of course, it was much easier and cheaper for the parents to be blamed for polio than it was for the government to keep public water free from contaminated fecal matter. [SOURCE 8]

Virus Outside Of The Body

A newspaper report in 1916 provided people with more accurate information about the polio virus, but it still was not up to par with what we know now.

It was acknowledged that the polio virus was transmitted from one infected person to another. While very correct, the scientists and doctors of the time did not know how long the virus could live outside of the body. It was published that the virus could live outside the body for “two to thirty days; the average seven to ten days.”

It is now known that the virus can live outside the body for up to two months. Caretakers in the early 1900s were being exposed to the polio virus even though they thought they were safe from it, no doubt increasing the number of people infected by the virus. [SOURCE 9]

“Isolation Is No Protection”

By 1932, doctors still had no clue as to how polio was spread. Australian doctors examined many cases and found that people who were hundreds of miles apart came down with the virus and had zero contact with each other. It was baffling to the point where some doctors declared that isolation offered people no protection from the virus. They also told the people that there was little point in taking flight from an area affected with the virus. It could strike them anywhere, at any time, and without a direct, known cause.

Mothers were advised to stop keeping their children under seclusion and were told that it was important that they kept baby’s appointment with the sisters at the Health Centre. Babies and young children needed their weekly weighing. Not getting the young ones weighed could make them even more susceptible to infant paralysis. [SOURCE 10]

Close The Borders

While shutting down schools was a popular solution to the spread of polio in the early 1900s, New South Wales went even further during an outbreak in 1937. The NSW police started to patrol the borders. All the bridges were under police control and vehicles were inspected. They would not allow any children to enter the state unless they were certified as being healthy and polio-free.

During this time, 20 new cases of polio were reported in Melbourne in a single weekend and there were three deaths from the virus. The fear that an infected person could cause more polio cases and deaths was very real. People were doing all that they could to stop the spread of polio. [SOURCE 11]

Music As Cure

There were a number of home remedies and “cures” for polio going around in the early 1900s. One highly interesting “cure” was a form of music therapy in 1910. Reported out of London, an “institution for the treatment of paralyzed children who are considered incurable in the general hospital” were given music lessons and instruments to help them overcome their paralysis.

One boy was cited as having suffered from polio and, as a result, his right arm was paralyzed. The staff gave the boy a drum and began working with him. The enthusiastic child eventually regained some use of his right arm and learned to play the drum through repetition. [SOURCE 12]

The Vaccines

It was announced out of Philadelphia in 1934 that a Dr. John Kolmer had invented a vaccine for infantile paralysis. He had already tested the vaccine on himself and on 25 other children, including his two children. The doctor declared the initial testing a success. No doubt it was a relief to the many people who read the report.

In 1935, Kolmer sent out 12,000 vaccine samples to doctors around the U.S. Sadly enough, when the results from the broad trials came in, Kolmer learned that his vaccine killed many of the children it was tested on.

The year 1955 saw another polio vaccine catastrophe. Called the “Cutter incident,” Cutter Laboratories released a polio vaccine and over 200,000 children were given the vaccine. Days after the mass vaccination, reports came in of children becoming paralyzed and dying from the vaccine.

At the same time as the Cutter incident was taking place, Dr. Jonas Salk released his polio vaccine. It worked and dramatically decreased polio cases worldwide. [SOURCES 13, 14, 15, 16]