I don’t know if women are far more cruel than men when it comes to murder, but it certainly is more shocking to hear of women, the people who are commonly thought of as caretakers, committing murder just for the sake of it. Old newspapers are filled with murders. Many of the murders are committed by men out of revenge. Some of the murderers are never discovered. A few murderers seem to slide by when the victim is labeled a suicide. The 1911 article below discusses the infamous serial poisoner, Louise Vermilya, and other infamous murderresses throughout history.

Louise Vermilya and What Famous Students of Crime Say About Cold Cruelty of Women

History Shows Women Criminals are More Ingenious, More Ferocious, More Diabolically Cruel Than Men.

A terrible point of superiority in the female born criminal over the male lie in the refined, diabolical cruelty with which she accomplishes her crime. — Lombroso.

The perversity of woman is so great as to be incredible even to its victim. — Caro.

Feminine criminality is more cynical, more depraved, and more terrible than the criminality of the male. — Rykere.

No possible punishment can deter women from heaping crime upon crime. Their perversity of mind is more fertile in new crimes than the imagination of a judge in new punishments. — Corrado Celto.

The violence of the ocean waves or of devouring flames is terrible. Terrible is poverty — but woman is more terrible than all else. — Euripides.

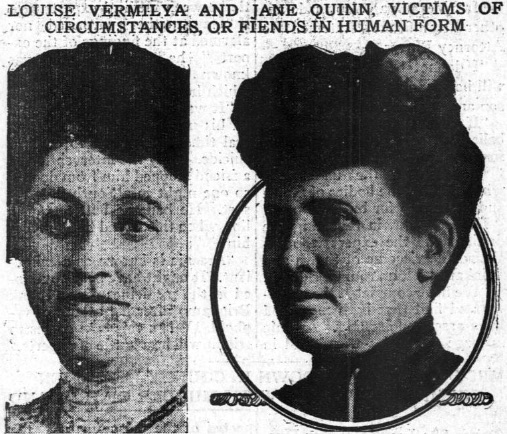

The cases of Louise Vermilya and Jane Quinn have features that call to my mind some of the famous cases in the annals of criminology.

The fine cunning in the use of the pepper box charged with death-giving arsenic — the obsession of the accused Vermilya in regard to corpses — her morbid love of seeing and handling the dead — these are things that make her case of peculiar interest to the student of crime.

The utter heartlessness of Jane Quinn in twice going through wedding ceremonies while the bodies of murdered husbands scarce were cold in the grave, and her utter lack of emotion when charged by the police with three murders, make her case rank only second to that of the Vermilya.

Passing over the case of Lucrezia Borgia, that much maligned Italian lady whose character recently has been patched up by the dissipation of the myth regarding her propensity for poisoning folks, we find in criminal annals many cases that go to substantiate the assertion of Lombroso, the great Italian criminologist, that though “females born criminal are fewer than male they often are much more ferocious.”

“History,” he says, “has recorded the mingled cruelty and lust of women who have enjoyed royal or popular power. We know of instances among Romans, Greeks and Russians, from Aggripina, Fulvia, Messalina, down to Elizabeth of Russia, Theroigne de Mericort and the female cannibals of Paris and Palermo.

“And the same may be said of Asia.

“Amestris, to revenger herself on a rival, begged Xerxes to hand over to her the rival’s mother. Xerxes did so. Amestris cut off the woman’s breasts, ears, lips and tongue and threw them to the palace dogs. Then she sent the mutilated woman home.

“Parysatis, the mother of Artaxerxes, caused the mother and sister of a rival to be buried alive, while the rival herself she ordered cut to pieces.

“Ta-Ki, the mistress of the Emperor Cheon-Sin, plunged him into vicious excesses, and when a rival appeared on the scene she had her killed and sent the body, cut into pieces, to the murdered woman’s father, whom she also caused to be assassinated.

“M.R., a case described by Ottolenghi, was a thief, corrupter of youth, a blackmailer, and all this at the age of 17.

“When only 12 she robbed her father. At 15 she fled from home with a lover, whom she left almost at once for a vicious career.

“She was extremely vindictive — on one occasion she conceived such a violent hatred for a rival that, enticing her into a cave, she poisoned her coffee and thus caused her death.”

Lombroso is merciless in his analysis of the feminine traits.

“What is the explanation?” he asks.

“We have seen that the normal woman naturally is less sensitive to pain than a man — and compassion is the offspring of sensitiveness.

“We also see that women have many traits in common with children; that their moral sense is deficient; that they are revengeful, jealous, inclined to vengeances of a refined, diabolical cruelty.

“In ordinary cases these defects are neutralized by piety, maternity, want of passion.

“But when piety and maternal sentiments are wanting and in their places are strong passions and intensely erotic tendencies, it is clear that the innocuous semi-criminal present in the normal woman must be transformed into a born criminal more terrible than any man.

“What terrible criminals children would be if they had strong passions, muscular strength and sufficient intelligence? And if, moreover, their evil tendencies were exasperated by a morbid psychical activity?

“And women are big children. Their evil tendencies are more numerous and more varied than men;s, but generally remain latent.”

In later days, there has been Belle Gunness, the red woman of the Indiana murder farm.

Did ever a male criminal show such utterly fiendish cruelty as this middle-aged woman of fifteen scarlet murders?

Did ever a male criminal overreach this woman who wooed men to her lonely farm with talk of love and marriage, only to slay them as they slept, and all for the lust of gold?

And apply Lombroso’s statements to the case of Louise Vermilya.

If the theory of the police be correct, think how this more cunning criminal than Belle Gunness must have sat in her House of Death at 415 East Twenty-ninth street, and planned to lure men to their deaths.

Think how she must have selected her victims, then with lavish displays of sweet womanhood woven a net of subtle flattery about him, as a spider about a fly.

Think how she made her home a place so comfortable that all men longed for it.

What was it that made Arthur Bissonette wish to marry Louise Vermilya, according to her own statement?

It was the home-like are that always pervaded the House of Death.

What was it that induced Richard T. Smith to woo this woman of many loves and deaths?

It was desire for such a home as his dead friend, Vermilya, had enjoyed and bragged of.

And then think of this woman sitting in the carefully planned home, scheming to induce the men she had drawn into her net to insure their lives in her favor.

Think of the diabolical ingenuity of the pepper box.

Think of the Vermilya, all smiles and womanly tenderness, asking the man whose death she sought if his food were flavored to his taste.

Think of her smiling and joking as she passed to the man whose life she longed for, the deadly arsenic pepper box.

Think of her gloating as she saw it used.

Think of her nursing the men she poisoned, and pretending to soothe the pain that she herself caused.

Think of her plotting the death of her own son, “who always was so good to me,” when that son attempted to wed a second time.

Think of her handing that son the insurance policy in her favor with the one hand, and the deadly pepper box with the other.

Think of her ghoulish visits to the morgues where lay those who had died by her own hand.

Is there, in all the red annals of the past, a better illustration for Lombroso’s statements than this woman, who, last Saturday, weighed down by the terrible accusations of the police, herself asked for the pepper box and attempted to end her own life?

And Jane Quinn.

There is less ingenuity shown in the crimes of which the police accuse this woman.

But are they less terrible, less cruel, do they evidence less utter heartlessness?

Picture the murder of Thorpe, her husband, and then herself, in widow’s weeds, marrying the man for whom she had slain Thorpe.

Think how, unweighed by sorrow or remorse, she sent one husband to follow the long trail of another.

If the theories of the police in regard to the lives and murders of Louise Vermilya and Jane Quinn be correct, then surely there is much basis for Lombroso’s merciless denunciation of the woman criminal.

Source: (1911, November 10). Louise Vermilya and what famous students of crime say about cold cruelty of women. The Day Book, pgs. 9-12.