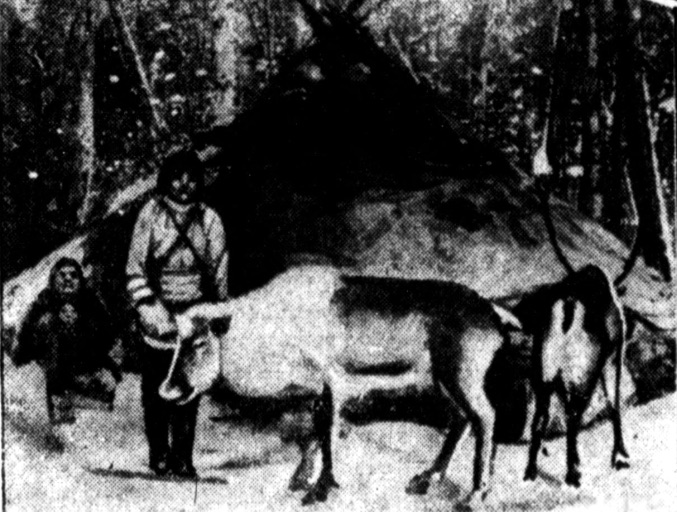

Newspapers from the late 1800s and early 1900s have numerous accounts of indigenous people from all over the world. This particular article covers the domestic lives of the Eskimos in Oo-ghee-a-book (King Island) in 1902.

AN ESKIMO VILLAGE

Few maps show Oo-ghee-a-book or King Island, which is situated in North Behring sea, about thirty miles south of the straits and about eighty miles below the Arctic circle. Its precipitous walls of volcanic rock rise almost perpendicularly from the deep icy sea to a height of nearly eight hundred feet, and the never ending surges of these restless waters dash he spray to meet the low hanging clouds that hover about this lonely rock.

The only place on the island where a landing is possible is on the south side. Here the face of the cliff is cut by a steep ravine extending upward to the level plateau which forms the summit of the island. There is no beach, and at all times landing is difficult and dangerous, and only possible during the most favorable weather.

The houses, some forty in number, are scattered without regard to order, wherever they can be made to hang on the almost vertical face of the cliff. They are so constructed and set on top of one another as almost to suggest one large communal dwelling, having perhaps, a far fetched resemblance to the cliff dwellers of Arizona and New Mexico, differing vastly, however, in material and mode of construction. The summer houses are square boxes of walrus skin stretched on frames of driftwood, lashed together and guyed to the rocks with thohgs, no nails, screws or other civilized methods of joining being used.

As in most Eskimo villages there is one house larger than the rest, known as the “Kazhime,” which answers the purpose of a public house or club, and its hospitality is impartially shared by the entire community. It is often the home of the young unmarried men, and the place of entertainment for strangers. It is also the place of general gatherers, where the long Arctic night is enlivened by the shouts and laughter of the half naked dancers, and the rude, monotonous music of the tom-tom. Here the gossips meet, here the Shaman performs his tricks of magic, and the hunters of bear and walrus relate their deeds of daring on sea and ice flow.

Inside the ordinary dwelling a low bench extends around two or three sides of the single room, which serves by day as a seat, and by night as a bed. The room is usually about ten or fifteen feet square, and in this single apartment a whole family, and sometimes two or three families, spend their entire indoor life. The household equipment is of the simplest and rudest description; a few wooden vessels and a curiously fashioned stone lamp comprise the entire culinary outfit. This lamp, fed with seal oil, emits more ill smelling smoke than light or heat, and serves all the purposes of a stove, but most of the food is eaten raw, or nearly so. Seal oil and walrus meat, and at certain seasons sea fowl, with an occasional dinner of tom cod or other fish, boiled or dried and eaten raw, form the almost unvarying diet of the King Islander. Of vegetables they know nothing from one end of their lives to the other. Tea and tobacco, their only luxuries are shared impartially by all ages and both sexes.

In appearance the King Islanders most resemble the Eskimo of the adjacent Alaska coast, who are the only people with whom they have any intercourse and with whom they are closely allied in their customs and superstitions, and even with these the difference in dialect renders communication very difficult. The custom of killing the sick and aged, commonly practiced on the Siberian coast, and St. Lawrence Island, is almost unknown, but the inexorable rigor of nature on this barren rock efficiently provides for the survival of the fittest only.

Sometimes the island has been swept by epidemics which have threatened extermination of the tribe; as in the summer of 1900, when disease carried off at least a third of the entire population. The previous winter had been a hard one, and the passing of the ice had found the people weakened by hunger and unable to take advantage of the spring hunting season; few seal or walrus were taken, and a whaler visiting the island to trade had left the disease which spread rapidly and disastrously, as it always does in the fertile soil of a primitive race. When the United States revenue cutter Bear visited the island on the 2d of July, 1900, many had died and nearly all were sick, but little could be done except to give them the food so much needed.

On the second visit of the Bear in August the island was found entirely deserted by the natives. Lean dogs wailed dismally from the rocks as our boat approached. Not a live human being was to be found, but the trail of the pestilence was everywhere visible.

Later it was learned that the surviving King Islanders had crossed over to the mainland and established themselves near Cape Nome and Port Clarence. Some have returned again to the island, but the times seems not far distant when the remnant of the tribe will be absorbed by the natives of the mainland, and one of the last and most interesting relics of the men of the stone age will pass into legend and tradition. [Source]