Ancient Egyptian mummies would be ground up and used for making paint. It is fascinating and gross at the same time — immortality in art, but the art is made of ground up human bodies.

The article below is from 1903.

Mummies Ground Up For Paint For Pictures

Afford Beautiful Tint for Brown Hair with Glint of Gold

Industry Threatened with Extinction from Lack of Material

Mummy — powdered mummy — makes one of the best and most popular colors used by artists. Every large dealer in oil paints sells powdered mummy and almost every manufacturer of pigments has a mummy department, where, in a spice laden atmosphere, amid surroundings picturesque and gruesome, young men and women grind up the dried bodies of Egyptian princesses and priests, mix the powder with poppy oil and bottle it for the market in little tubes of tin.

This business of making paint out of mummies is of long standing, but it is now threatened with destruction. For the supply of mummies is daily growing scarcer, while the demand for them increases. If, then, for the benefit of the museums and people of the future, any mummies at all are to be preserved, the commerce in them must at once cease. That is the view which the government of Egypt is taking, and the governments of France and England are supporting her. In the London and Paris newspapers have appeared of late a number of articles urging the instant prohibition all over the world of the mummy paint industry.

These articles in the newspapers were the first announcement that many persons had that such a thing as the mummy paint industry existed. Therefore, the articles occasioned a great deal of curiosity, and men and women, stopping in shops devoted to artists’ supplies, said:

“Do you sell a paint called mummy?”

“Yes, this is it.”

“Well! And here is the name marked on the tube, too! Is this paint really made out of mummies?”

“Yes, of ground mummy and poppy oil.”

“It is very strange. It is gruesome. It is horrible and sad and fascinating.”

The mummy paint industry, undisturbed by all this public interest and all this governmental condemnation, moves onward calmly. The old masters, when they desired to give a subtle brown tint to a woman’s hair, dipped their brushes in a mummy’s powdered dust and painted brown hair of that bright sort which turns to pure gold in the sunlight. Mummies figure in the daybooks and the ledgers of every paint factory. Turn to their stock accounts, and these are common entries:

To 2 mummies at $175 — $350

To 10 lb mummy (Thebes) at $6 — 60

To 12 lb mummy (Memphis) at $3.50 — 42

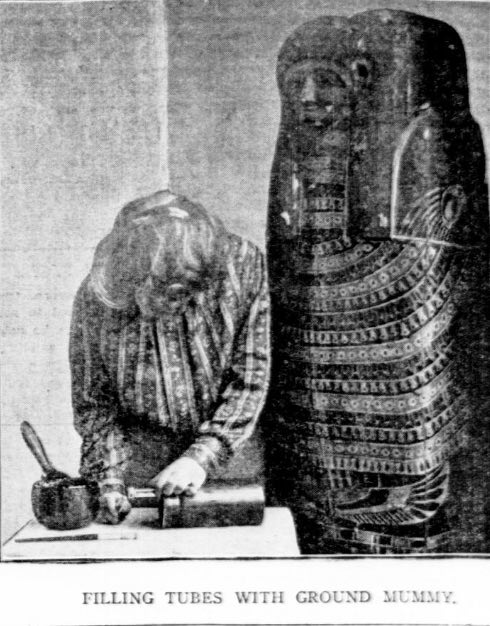

In a Philadelphia factory, the other day, a mummy had just arrived, and they were busy grinding it, with poppy oil, into a smooth brown paste. The work went on in a small room that smelled of myrrh and cassia. The mummy case stood in a corner. It was decorated with small figures in red and green and gold and black, and the carved and painted face upon it was imposing and grave. Beside it a young girl, bending over a small table, filled tubes with powdered mummy. There lay at her feet a great bundle of faded yellow linen, the wrappings of the mummy which numbered hundreds of yards.

A young man was grinding on a stone slab bits of mummy. The implement he used was a pounded stone with a flat base. The mummy’s head lay beside him and near it were a few bones. Now and then the young man moistened the dark powder on the slab with a few drops of poppy oil.

“This mummy,” said the manager, “will make enough paint to last two years. The paint is called mummy – simply that. The demand for it is not enormous. It is not used to paint bridges with, you know.

“No one knows just why powdered mummies should make a brown of unique excellence. It is surmised, though, that the bitumen in which they were steeped in their embalming is what gives us this fine brown.

“I have heard of the condemnation of our business that has grown out of the growing scarcity of mummies, and with this condemnation I can sympathize. I can’t sympathize, though, with any sentimental condemnation of the business. For mummies are the fruit of a desire to preserve the dead in a beautiful and seemly manner, and it appears to me that, as the bright, brown hair of a woman’s portrait, a mummy is preserved, after all, in a more beautiful and seemly way than if it still continued to desiccate in an Egyptian crypt.”

He lifted up a portion of the mound of faded linen and s slight dust arose, faintly odorous of spices.

“These narrow strips of linen,” he said, “are the wrappings of the mummy. There are probably five hundred yards of wrappings here. We have had mummies swathed in as many as 1.200 yards by actual measurement. To undo so much linen, were the task carefully performed, would take two or three days. We cut the linen off. It saves time.

“We find each toe separately wrapped. Each finger is separately wrapped. Round and round the toes, the fingers, the arms, the legs, the body and the head the wrappings go, hundreds of times. They are applied with wonderful skill. They serve at once the two purposes of a protection and of an ornament, for when they are completed they make a firm, thick, almost impermeable envelopes, and this envelope reproduces accurately the human figure. The mummy within will be shrunken; it was shrunken, I have no doubt, when the wrappings were applied; but the wrappings correct all its defects; they fill out the hollows and angles; like costumes artfully padded, they appear to cover a figure of great beauty.

“My workmen don’t object to making paint out of mummies. Why should they? Do medical students object to dissecting? Do anatomists object to preparing the pure white skeletons, articulated with silver wire, that the surgical dealers sell? All these things are for the good of mankind, and they do not harm the dead.

“I buy my mummies through a dealer in Paris. Where he gets his stock I don’t know, but he is never at a loss to fill an order. Mummies vary in price. Those of Thebes are the best, and may bring $250 apiece. A big factory like ours will buy a whole mummy at a time. A smaller one will buy a body, a leg or a couple of arms. The little factories buy their mummy powdered, in five or ten pound tins — foolish thing to do because these tins are apt to be adulterated with earth or asphalt.

“My business naturally has caused me to take an interest in mummies. I have read from time to time various monographs and articles on the old Egyptian processes of embalming. It seems that three thousand or four thousand years ago, when embalming was at its height in Egypt, there were suburban settlements given over to this ghastly business. Such a settlement was called a necropolis. It would be engaged upon the embalming of nine hundred or a thousand bodies at a time, so huge was the business done. It was not, though, a business. It was a rite, a religious rite. Those who practiced it were priests.”

Source: New York Tribune. Newspaper. December 20, 1903.