In the late 1800s to early 1900s, Central America was the place to go searching for ancient ruins of past civilizations. And while it is a place still filled with mysteries and ancient secrets, archaeologists from the past shared an almost childlike excitement over each and every discovery.

Ruins of a Vanished Race Found in Central America

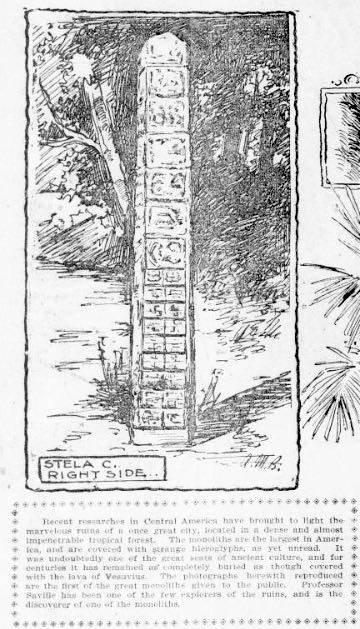

Of all the ancient cities in Central America the forest covered ruins of Quirigua are perhaps the least known. They are situated in the valley of the Motagua or Montagua River, about half a league from the left bank, and about sixty miles from the mouth, where it empties into the Caribbean Sea. Entirely overspread with the densest tropical vegetation found anywhere in Central America, they have remained unexplored and their extent unknown. Now, however, the transcontinental railway, in process of construction from Puerto Barrios to the city of Guatemala, passes through the valley at a distance of not more than a mile from this wonderful group of remains, and they are thus brought within reach of the traveler, who can visit them without undertaking the exceedingly difficult passage over the Mico Mountains.

These ruins were first brought to the attention of the world in 1841 by the celebrated explorer Stephens, who did not visit them, but we are indebted to his companion, the artist Catherwood, for the meager notice which appeared at that time, with several poor drawings of the monoliths. Later they have been visited by several explorers, who have added little or nothing to our knowledge of the place.

In 1881, and again in 1883, Alfred P. Mandslay, the great English explorer, spent several months there, photographing and making paper molds of some of the most interesting of the stone sculptures. He has up to the present time published only brief accounts of his work and none of his photographs. From his work in reproducing in plaster the immense stone carvings the American Museum of Natural History has profited through the generosity of the Duke of Loubat in securing for its collection casts of the largest two sculptures in stone yet discovered in ancient America.

As yet, however, no systematic excavation has ever been carried on there and no adequate description has been published of this one of the most important ruined cities in the New World. No field in Central America offers a richer return to the archaeologist. It is not at all improbable that still more valuable sculptures may be buried in the paradise of luxuriant growth, in which cacao, quinoa, india rubber, mahogany, bamboo and gigantic ferns abound, through the depths of which the jaguar, puma, tapir and peccary roam at will, while birds of brilliant colored plumage are exceedingly numerous.

The ruins consist of a large number of mounds, pyramids, terraces or platforms, both square and rectangular, measuring from six to forty feet in height, some standing in groups of four arranged around a central square or plaza, while others occupy an isolated position. The greater number of these structures have been faced with squared stones and had flights of stone steps on one side leading to the top.

Owing to the density of the forest it is impossible to accurately describe these structures. This can only be done by cutting down and burning the undergrowth, and an examination of the sculptures is made by having several Indians with machetes cutting a path in advance. These Indians are such skillful woodsmen that one can usually follow them as they dexterously cut out a “tunnel” through which to pass.

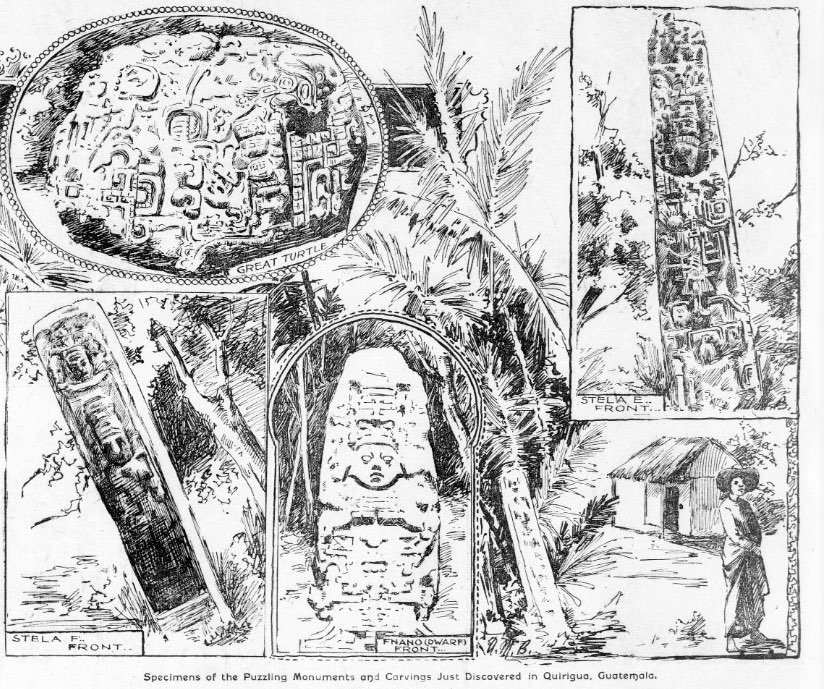

There are three principal structures in the main group, near which are standing thirteen large monuments in the form of stelae and large, rounded masses carved to represent grotesque animals. These are in what is probably the great plaza, or square, the heart of the ancient city.

At the northern end is a large rectangular terraced structure about 300 feet long from east to west and 175 feet from north to south. Near the northwestern corner is what appears to be an artificial lagoon, or pond, which probably has an outlet in the Motagua River. At present it is a stagnant, malaria breeding pond, nearly choked with decaying vegetable matter.

At the southern base of the structure are standing three stelae, or monoliths, ranging in height from fourteen to eighteen feet and having carved on the front and back representations of human figures. On one is a man with a chin beard. Both sides are entirely covered with hieroglyphic writing in the form of squares, called katuns.

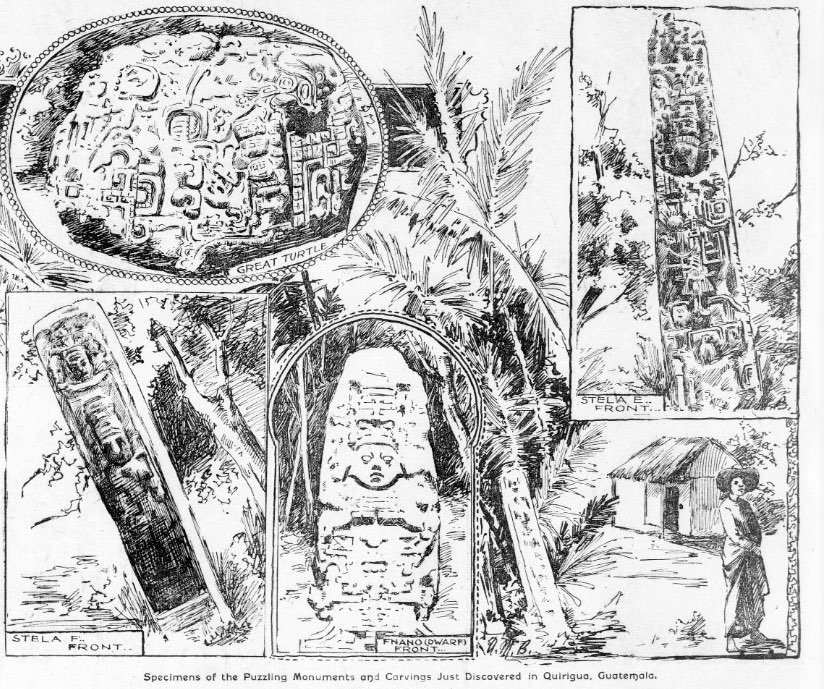

On another, called stela C, is perhaps the most important hieroglyphics inscription yet found in America. It consists of two kinds of writing. The upper half of the inscription is in pictures, elaborately and intricately carved, while in the lower half are the abbreviated and conventional characters such as are commonly found in the Mayan glyphs.

Undoubtedly an unraveling of the picture writing will aid greatly in deciphering the hundreds of inscriptions which are found in the territory once occupied by the Maya race, formerly the most advanced of all the ancient peoples of America. On only two other monuments is this form of “picture” writing found, one example being in the ruins of Copan, Honduras, where the back of a stela is entirely covered with pictures.

About two hundred feet south of these three monoliths are the two highest monuments which have been discovered in the new world. The first, known as Stela F, stands twenty-five feet above the ground; the other, Stela E, is twenty-two feet high. The first mentioned is leaning at an angle of forty-five degrees, and as it stands there must be at least ten feet of its length under ground. There are full face human figures carved on the front and back, and a hieroglyphic inscription on either side. It has settled perceptibly since Catherwood’s visit in 1841. Fortunately it has been accurately molded by Mr. Maudslay in plaster, and a cast is in the American Museum of Natural History.

The second stela, twenty-two feet high, is by far the most artistically carved of all the standing monoliths. It has large, full face human figures on the front and back, and both sides are occupied by hieroglyphs.

The ears of the person are almost covered with huge ornaments. The breast and body to the waist are loaded with ornaments, and an elaborately worked loin cloth hangs from the waist, down between the legs to the feet. In the right hand is held a kind of wand or scepter, much resembling a “jumping jack.” The upper part is a grotesque little figure, with a long nose, representing a deity. From the bottom of the stick hang feathers. The left hand is covered by a shield, on the face of which is a mask, probably a representation of the sun god.

Near at hand are two fallen stelae about ten feet in length, entirely covered with moss and vegetable debris. About 800 feet south of these two large stelae is a high truncated pyramid, more than 150 feet in diameter at the base. A short distance east and northeast are three large monuments, and from 300 to 400 feet south, in a plaza enclosed on three sides, is another group of stelae.

The most important of these is in the form of a conventionally carved gigantic turtle, the most extraordinary sculpture in Central America. Roughly described it is a cube about eight feet in size and probably weighing twenty tons. It is entirely covered with picture and hieroglyphic writing, and representations of a symbolic character, among which are several exaggerated animal and human faces and figures. Maudslay spent much time in securing a plaster mold of this stone in more than 400 pieces.

In addition there is an interesting figure carved on another stela, representing a woman, with fat, round cheeks, which has been called the enano, or dwarf.

Besides the monuments now standing there are several fallen stelae, some complete, while others are broken. They are all covered over with moss, which hides the most delicately carved lines, so that in order to photograph them it is necessary to have them carefully cleaned with brushes.

The rock out of which they are carved is a gray porphyry, the quarries being several miles from the ruins and more than 600 feet above the valley. The stones were probably all transported in the rough and carved on the spot where they now stand, the debris being used in the construction of the pyramids and edifices. The labor of transporting these immense stones must have been stupendous, and indicates a very high knowledge of mechanics.

In the mounds and pyramids all traces of palaces and temples of stone have disappeared. Such edifices are entirely destroyed, so much so that Maudslay was of the opinion that these structures did not support stone houses, but buildings of perishable material, such as wood or adobe bricks. One excavation made, however, proves that stone buildings once existed, for in the principal pyramid several rooms have been uncovered, revealing the triangular Maya arch, with walls to the rooms, made of nicely laid stones, covered with stucco or plaster, and with smooth cement floors.

Source: The San Francisco call. (San Francisco [Calif.]), 23 Oct. 1898.