The article below, published in 1915, claims that German spies hid in the catacombs of Rome during World War I.

Searching the Catacombs of Rome for Hidden German Soldiers

The world has heard many strange accounts of the exploits of German army spies in all parts of Europe, but surely the strangest of all is that they have congealed themselves in the Catacombs of Rome in order to spy on the operations of the Italian army.

Where the earliest Christians constructed these wonderful secret hiding placed in the rock to escape the blood thirsty tyranny of the Roman emperors, these efficient moderns have concealed themselves for the purposes of war. Where the earliest Christians sought refuge to conduct their sacred services in safety, the modern militarists have made a stronghold for the most subtle and deadly objects of the gospel of war.

Even the construction of gun emplacements in factories on French soil and the storing of munitions in disused French quarries by the Germans can hardly equal this exploit.

Both before and after the outbreak of war the Italians conducted their military preparations with a secrecy remarkable even when compared with the precautions of this character taken by all the other Powers.

Before the war they started to weed out and expel all the German and Austrian spies and secret agents who swarmed from one end of Italy to the other, and followed every occupations, notably those of hotel waiter and professor.

Still they found that remarkably accurate information concerning Italian plans was going to Austria and Germany. It was then that an officer of the Italian army “Intelligence Department” caught sight of a spectacled, very Teutonic looking person living in an obscure hovel near the Catacombs. He watched him and found that he was making use of one of the many secret entrances of the Catacombs.

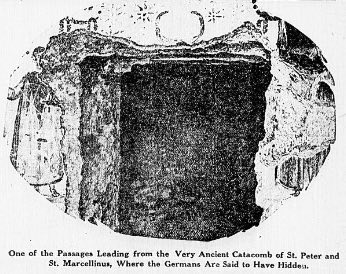

The Italian War Office was aware of the significant fact that recent explorations of the Catacombs have been mainly in the hands of alleged German scientists. The Catacomb of San Sebastiano, for instance, was until a month ago the scene of busy German operations, and this happens to undermine an important Italian military post.

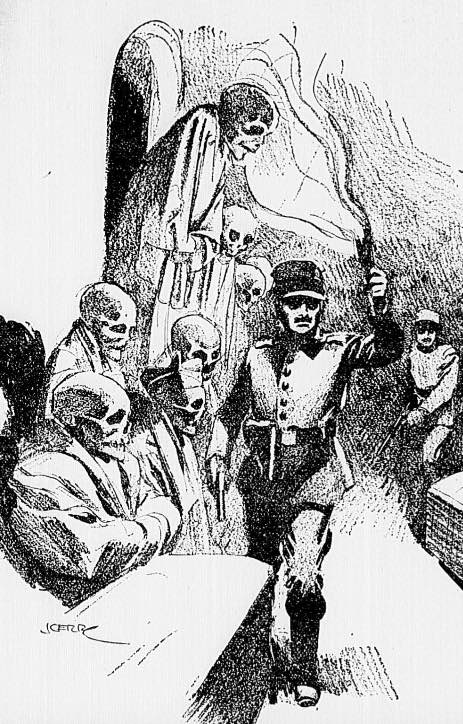

The Italian soldiers made a descent in force and captured a number of Germans who had concealed themselves behind a rampart of ancient skulls in the depths of the Catacombs. They were supplied with provisions for months and portable electric lights, with which they could find their way in the darkness. The Italians are stated to have seized a quantity of papers in which the Germans had made plans of Italian fortifications and notes of military preparations. Some of these had been cleverly concealed behind the altar of the oldest chapels constructed by the early Christians.

The Germans had also made many sketches of religious decorations in the Catacombs, which are unrivaled in the field of early Christian art, but whether they had done this from pure love of art or to cloak their other operations may be questioned. It is equally uncertain whether the Italians have captured all the Germans who were concealed in the Catacombs.

It seems that the Germans used this place as a kind of headquarters, where they could spy on the plans of the War Office in Rome, assemble information, dispatch messengers to Germany when there was a good opportunity, and perhaps make an attack at a critical moment on the local defenses. The Italian War Office naturally refuses to reveal all that it has found out concerning the German espionage operations.

The Catacombs furnish an almost impregnable place, for there are about sixty of them in all, with uncounted entrances and the winding passages within them are perhaps two hundred miles in length. Their exact length has never been measured, but as they wind about one under the other until there are often five or six of them in depth, it will be easily understood that they may have at least that length. They are just outside the ancient city walls and are excavated in a kind of rock called tufa, which, though soft, holds its form when excavated.

The Catacombs now consist of an endless maze of galleries. This was not the original condition, but the result of the gradual evolution through centuries, during which one generation after another added to their complications. During the first and second centuries some of the Roman Christians built small catacombs for the burial of themselves, their family and friends. These usually consisted of a square chamber, in which a single gallery ran around the sides, about eight feet high by three feet wide, in whose sides were cut recesses called “loculi,” one above the other, to receive the bodies.

Persons of distinction were buried in special chambers, or cubicals, which opened out of these galleries, and for these burials carved sarcophagi were often used, placed in arched niches or “arcosolia.” These recesses, it appears, have been used as hiding places for the food, fuel, and papers of the German spies.

Usually some early Christian martyr was buried in such chambers and his tomb served as an altar at which religious services were afterward celebrated. The German agents evidently supposed that the sacred character of these constructions would preserve them as against search, but the military authorities have proceeded with stern disregard of religious sentiment.

As the number of Roman Catholics increased in early times and consequently the number of burials, the originally small catacombs were honeycombed with galleries and extensions. When one story of them was no longer sufficient, stairways were made, and another system of galleries excavated underneath. This was followed, if necessary, but a third, fourth, fifth, or even sixth story of galleries.

The catacomb of St. Calixtus occupied a leading position, and here the bishops of Rome of the third century were buried in a special crypt. It is said that this catacomb concealed the principal headquarters of the German spy organization.

During this ancient period passages were gradually cut to connect the neighboring catacombs, thus joining the whole of them together into an endless labyrinth, through which nobody but an experienced person, such as one of the monks or church officials put in charge of these places, was likely to find his way. Indeed, there are gruesome stories of curious Americans in modern times who have tried to explore these catacombs alone and have lost themselves and starved to death. A trained “tracker,” however, with proper lights and some method of marking his track, would have no great difficulty in finding his way out again after a trip to the deeper recesses. The German spies were, of course, trained to such work. That is why it is believed that some, at least, of them have escaped to the very distant recessed of the catacombs. It is uncertain now whether they are starving to death or not, but it is thought more likely they are supplied with provisions and with true Teutonic tenacity are holding out until the vigilance of their pursuers relaxes and they are able to do some more spying.

The catacombs reached their highest development in the middle of the third century, when Roman persecution of the Christians was carried to extreme violence. Persecuting officials and mobs, refusing to recognize the sanctity of the Christian places of burial, entered the catacombs and began to deface their chapels, tombs and sacred decorations. Christians then destroyed the entrances with their oratories, their open stairways and their halls for the Christian love feasts, filled up the galleries and made other and secret entrances from neighboring sand pits. Thus they completed the inconceivably intricate and confusing character of the passages, which has so strangely furnished a basis of operation for military spies in our day.

During the terrible persecution of the Christians under Emperor Diocletian, hundreds of martyrs were buried in secret here, and the enlargements necessary were carried on with the same secrecy. Even after persecution had ceased under the Emperor Constantine, burials were commonly made here because the place had been rendered sacred by the bones of the martyrs. At last these reasons ceased to appeal to the people, and the catacombs were no longer used for burials or religious services. For several centuries in the early middle ages they were the objects of pilgrimages by pious Christians from all over Europe.

Then came the disastrous invasions of Italy by Goths and other Teutonic barbarians, and by Vandals, Lombards and Saracens. Once more the catacombs served a vital purpose to Rome. The treasures of the city were in many cases carried here to save them from the barbarians. The entrances were once more closed up and in many parts of the galleries were filled, in order that the barbarians might not lay hands on their sacred relics and treasures and deface their sacred decorations.

From the invasion of the Saracens in the tench century down to the fifteenth century the catacombs were more or less forgotten by civilization, but there is no doubt that they served as a refuge for many brigands, rebels and other turbulent characters, who preyed upon travelers or fought against the authorities during the stormy medieval history of Rome.

During the great Italian Renaissance they were reopened, and since then they have been more and more explored with wonderfully interesting results, but even today their full extent is not known, and the art treasures which they contained have not all been studied. Perhaps at this moment some German spy, with his little electric pocket lamp, his mind divided between espionage and archaeology, is gazing with interest upon the earliest pictures of the holy Apostles which have not yet been seen by the eyes of the modern ecclesiastic or archaeologist.

Source: Richmond times-dispatch. (Richmond, Va.), 27 June 1915.