The hard and brutal lives of the cannery workers in the early 20th century were the subject of much discussion beginning in 1912. People from the upper classes discovered the miserable lives of these people, often entire families, and brought the cannery workers into the light of the general public.

It was through the undercover work of numerous societal heroes that the plight of these workers were changed. Sadly, however, some of the conditions described back in the early 1900s can still be found today among our migrant workers who are often treated as less than human despite their hard work and benefit to our economy.

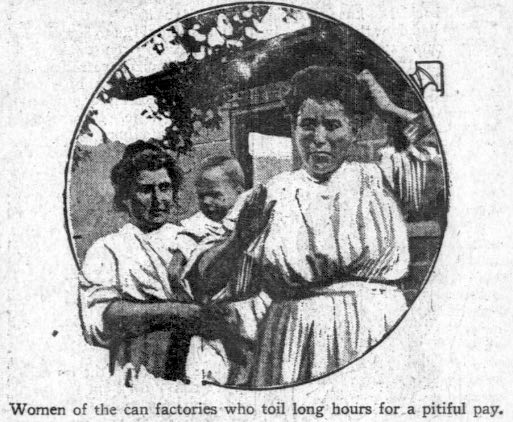

Long Hours And Low Pay

The farm harvests were coming in at a steady pace back in 1912 and the canning factory in Mohawk Valley, New York was working the women and children at all hours. These cannery workers were not paid by the hour, however, but by the weight of produce they prepared.

During the pea harvest of that year, it was recorded that one woman worked 119 and 7/8 hours in one week. Mrs. Kate Donnelly, a capper, showed up at work each morning at 7 a.m. She carried her three meager meals with her and usually worked up until 2 a.m. the next morning. Two other women worked 115 hours that week, and there were reports of numerous workers who had to give up and walk away from the job because they could not keep up.

For all their work, their pay was meager. The average weekly wage was $4.70. A few of the workers pulled in a little more than that and quite a few workers would only bring in a little over $3 a week. [1]

Child Labor

Child labor laws fluctuated heavily in 1912, with each state making and changing laws to suit the whims of businesses. In New York State, for example, cannery owners made certain that a child labor investigation was never published because of the deplorable discoveries of child abuse within the industry. The cannery owners insisted that it was the greed of the parents, not the canneries, that put children as young at 5-years-old inside the cannery sheds.

Tommy Cecora, who was age 15 at the time of the newspaper report, had worked during pea season in one of New York City’s biggest canning factories. In one week he worked 108 hours. Children under the age of ten also worked all day and into the night. Most of these children sat inside small, wooden sheds built six inches away from the main factory and prepared fruit and vegetables for canning.

Children, despite working away their childhoods, were given the lowest pay imaginable. Most children in the canneries only made three to twenty cents a day, being paid only a fraction of a cent for every pound of produce they prepared. [2]

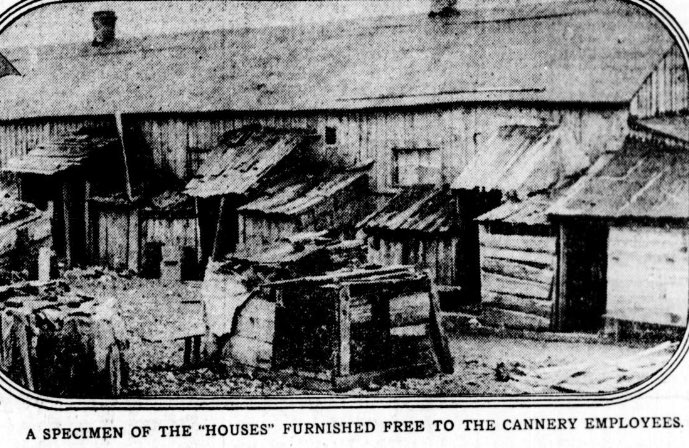

Free Housing

One method canneries used to bring in workers was to offer free housing. Poor families from the city were shipped into the cannery camps on the promise of fresh country air, free housing, and decent wages. What the poor actually found were shacks filled with up to 20 families, no running water, and overflowing outhouses.

One newspaper investigator went to check out the free housing in the small towns of New York, and what she found was appalling. In one cannery housing center, she discovered three families living in a one room shed. The adults worked all day and night, and nine young children spent all their time inside the shed. The shed smelled of sewage and one of the children had red sores covering his face. There was no clean water supply for the families and flies infested the building.

At another cannery, eight-foot-square shacks were set up for the poor. The arrangements were one family per shack. Again, there was no running water and the nearest water source was a canal, 1,500 feet away.

At a cannery outside of Syracuse, the workers were housed in a long shed that was divided into stall-like apartments. During the harvest months in 1912, the 20 apartments housed 45 to 50 families. The families slept on wooden bunks in the seven by ten feet rooms. If they wanted to cook, there was a separate open shed that housed three wood stoves. [3]

Paid in Company Store Credit

For all of their hard work, many men, women, and children were not paid in cash. Instead, many canneries, especially seafood canneries, paid their workers in store credit. This meant that workers could only buy items at the company store and nowhere else.

In 1914, it was reported that an oyster cannery company store charged ten cents for a loaf of bread when regular stores charged only six cents. Children’s shoes that were normally 98 cents costs $1.75 in the company store.

There was no way that families working for store credit could escape or leave the dreadful conditions of their jobs. Instead, parents and their children had to work over twelve hours a day just so they could afford the most basic necessities at the company store. [4]

Malnutrition and Starvation

The Alaskan salmon canneries were infamous for nearly starving their workers and feeding them inedible or spoiled food. Back in 1919, recruiters from the Alaskan salmon canneries would travel down the coast and make stops along the California coast to find workers. The recruiters promised the workers free housing, food, and a $200 paycheck at the end of a four-month contract, but most men never saw the money promised to them.

The new recruits were boarded onto boats and taken to Alaska. Unbeknownst to most of the workers, they were charged for the journey, which was taken out of the $200 payment. After arriving at one of the canneries, the men were then forced to work sixteen-hour days. There were no days off and no holidays.

One of the biggest problems at these canneries was malnutrition. The workers were barely kept alive on a diet of rice, beans, and kelp. In spite of such a pitiful diet, the overinflated cost of the food was deducted from the $200.

The men that survived the ordeal for the full four months were returned to California by boat. One man complained that the ship’s drinking water was stored in unclean gasoline drums and the men on the ship became sick on their return home.

Upon arriving to their native cities, the men were given their pay. After all of the deductions the cannery owners made, many men did not have enough money to buy themselves a single meal. [5]