Old newspapers loved publishing moral pieces while spreading “friendly” neighborhood gossip at the same time. The article below, published in 1913, is about a man who ran cheap gambling rooms and made his fortune. The man’s family later lost all the money to folly.

The Curse that Lurks in a Gambler’s Gold

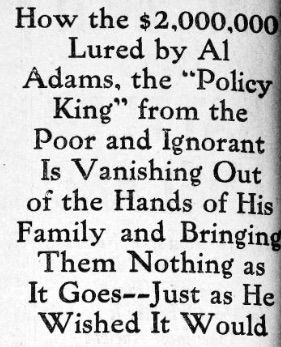

The news that Walter C. Adams had declared himself a bankrupt calls attention anew to the curse that is commonly believed to lurk in gambler’s gold. The money that is earned by gambling never sticks, according to a common adage, and by another we are informed that what comes easily goes in the same way.

Walter C. Adams is a son of Al J. Adams, the “policy king,” who, starting his earning life as a brakeman on a railway train, ended with a fortune of $2,000,000, extorted from the poor and credulous in a policy shop. Adams, after serving a term in Sing Sing for swindling, said angrily to a friend who wished to effect a reconciliation with his alienated family:

“Don’t talk to me about them. I hate them all. They waste my money. They’ll never have any luck!”

The man whose heart was filled with hatred for his own, and who cared nothing for the poor families whom he had made poorer and more wretched, died by his own hand less than seven years ago. Under the curse that lurks in gamblers’ gold and the family curse he uttered, the millions he accumulated by fraud are melting away much faster than gamblers’ gold usually vanishes. For, besides having the rate of vanishing of gamblers’ gold, dishonestly won and accumulated at the expense of misery in wretched homes, its speed in disappearing is doubled by the curse Al Adams himself laid upon whatever his family handled.

After seven years, Walter Adams’s share of the millions has gone as a late winter snowbank melts under a hot April sun, or a soap bubble vanishes when blown by an impatient child. He has gambled away a gambler’s gain.

The share that came to his daughters has gone by way of their several husbands, for each has had two and one has been twice divorced, the other was divorced and separated from her husbands. What remains to one of them will soon be dissipated in the Great White Way, for she has gone abroad, intending to go upon the stage, and a score of unscrupulous managers will star “Al Adams’s daughter” as long as a rag of her father’s money remains.

Nor has Mrs. Adams, the “policy king’s” widow, been exempt from the ill luck that followed the ill-gained gold, nor the curse of the old gambler himself, for much of her portion has been wasted in litigation and in huge fees to psychic persons whom she employed to follow her children and try to keep them out of bad company.

Mrs. Lillian Rosenthal, mourning over the murder of Herman Rosenthal and grieving as much at her destitution which followed, said, “None but bad luck follows gambling.”

Pat Sheedy, a gambler of international notoriety, and friend of the late “Big Time” Sullivan, of tragic fate, said while the gambler lay on his death bed: “No boy ought ever take any but the straight road. Nothing but bad luck waits for him in the other.” Pat Sheedy died poor. Herman Rosenthal left his widow in actual need. The dissipating of the Adams millions is but another proof of the truth that is in common saws. Trace the inescapable truth in the history of Al Adams and his family.

While Al Adams was a brakeman on a freight train of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad, dissatisfied with his lot and seeking even then what he called “easy money,” he met Zachariah Simmons. Simmons, watching the gigantic system of theft of Boss Tweed, conceived the idea that another means of building up a fortune could be devised by wringing the pennies from the poor and ignorant. Simmons established a policy business and, recognizing in Adams a soul as unscrupulous as his own, took the brakeman into his policy shop. Adams was from the first blind to the misery his penny villainy wrought in wretched homes. He only knew that these small, trickling streams formed a river of gold that emptied into his pockets. Taught well by his instructor, he soon pushed Simmons out. Simmons left cursing Adams.

“Make the money,” he said as he slammed the door until the copper pennies on his former partner’s table rattled, “and may it choke you!” It did, in a way, for as Adams’s fortune grew and grew, the pile of poor men’s pennies rose and rose about him, and though he had them changed again and again to gold, the piles rose higher and higher until they oppressed and all but suffocated him.

“That’s the man that steals from little children,” said his neighbors, and Al Adams shrugged his shoulders. The shoulders were covered with a fur overcoat earned by what were known as his “kindergarten games.” He sent his agents to the boys in the public schools and enticed them into roulette games. He backed poolrooms where horsecar drivers and longshoremen played the ponies at twenty-five cents a change. At one time he was the controlling spirit in one hundred cheap gambling places in New York.

As he grew richer he built a block of apartments. Their origin becoming known, some one dubbed them “The Policy Flats.” He moved farther uptown and bought a splendid house in Eighty-fifth Street, but daily placards, “Here Lives King Al of the Policy Shops” and “Down with the Policy King” were plastered over its walls. Adams never had the marauders arrested because he did not wish to advertise his infamous business.

At last this Napoleon of the povery stricken and credulous met his Waterloo. Captain Norton Goddard, discovering that the poor of the city were being drawn into evil habits by the wide reaching policy shop nets; that they neglected their work to be at the daily lottery drawings; that they drank more and worse whiskey after each loss that went to swell the revenue in the “king’s” exchequer, called on Adams, and, showing him the wrong he was doing, begged him to cease his wholesale depredations. Adams laughed at him.

“Then I shall fight you,” said Captain Goddard, taking his departure, “and when I fight I generally win.”

Adams, secure in his “paid protection,” went on with his policy business. But sometime, somewhere, such “protection” fails. He found himself facing Captain Goddard over a police station desk.

“I’ll move my policy shops out of your district,” Adams said, facing his enemy, his face pallid.

“I’ll move you off the Island of Manhattan into Sing Sing,” said Captain Goddard. In the trial that followed, Captain Goddard, looking at the craven old gambler from his place on the witness stand, said, “Al Adams is the meanest man in New York.”

Judge Scott, when he sentenced him to hard labor at Sing Sing for a year, repeated the branding sentence.

Adams came out of jail defiant, but his heart was filled with hatred. He went to the Hotel Ansonia to live, uttering his curse upon his family.

At the offices he maintained at West Thirty-fourth Street, which seemed to be the office suite of a prosperous broker, there were bitter quarrels with his family. Once there was a rumor, after high words and shrill voices within penetrated the handsome ground glass doors and reaching to the street, that his son had treated him in the manner for which a clergyman in the West was recently indicted. The rumor was that in a heat of a quarrel the younger man had struck the elder. In this magnificient suite at the Ansonia, there were other scenes and angry voices.

It did not surprise other guests when they heard that Al Adams was dead. Rumors of murder pressed close upon the news. Sheriff Harburger boldly said, “I believe he was murdered and that the murderer is in this room.” But the Coroner found a verdict of suicide. “The meanest man in New York” had tired of life, that official said. “There is nothing more to it.”

The curse of the Adams millions extended from their creator to his elder and favorite daughter. Evelyn Adams married Robert Armit, a Mexican mining operator. It was thought the ambition of the Adams girls and of their father was to be realized. One of them would get into society. But Mrs. Armit quickly returned from Mexico and sought a divorce. “My husband lost nearly all my money, Your Honor,” she said to the Judge.

“How?” asked His Honor.

“He pawned my jewelry and gambled away my money.”

“Gambled!” exclaimed the usually impassive Court. The memories of every one in the courtroom ran back to the petty gambling in Al Adams’s chain of policy shops.

Mrs. Armit took a house in Newport and tried to get into society. Newport, that strains at little things and swallows great ones, declined “Al Adams daughter.” The policy “princess” knocked in vain at its gates.

Hoping to enter American society by the back door of Paris, she wedded Paul Ernest Napoleone, of Paris, and Newport looked from behind closed blinds at the spectacle of Mrs. Armit driving from one church to another, offering a thousand dollar wedding fee to any clergyman who would marry her, though a divorcee. Her quest being finall successful, she sailed for Paris. But she returned from France almost as quickly as she had decamped from Mexico. She secured a divorce from the Frenchman. Meanwhile each husband had been a luxury. Al Adams’s daughter’s share of his fortune was growing less and less.

Ida Adams wedded the man about town, “Jack” Gallatin. More or less directly from the altar, Mrs. Gallatin went to the courts. She asked to be separated legally, as she was in fact, from her short term husband.

“Do you desire any alimony?” the Court asked her. The bride, with aplogies to the Court, laughed and looked at her attorney.

“If she asked for fifty cents a week she wouldn’t get it. The truth is she has been supporting him,” asserted her lawyer.

The bridegroom asserted that she had promised to perform that function. He said: “She nearly drove me out of my mind by her curious acts. One night she jumped off a yacht at midnight.” It developed in this airing of household linen that Eithel Kelly had celebrated “Jackks” nuptials by suing him for breach or promise and that his bride had paid $20,000 to lift the lien on his affections.

“I paid much more than they were worth,” she said.

Freed first by separation, then by divorce, “Al Adams’s baby” contracted another and still briefer marriage. Last year she became the bride of Francis Baldwin Anderson on May 21 and left him one week later.

“Wouldn’t Mr. Anderson’s family receive you?” asked a plain spoken friend.

“I was only there a week,” was the reply.

First families, whether of New York or Kentucky, could not and would not welcome a daughter of Al Adams. For Al Adams’s daughters marriage meant not social gain, but financial loss.

Mrs. Adams, in her mansion, was growing restive under the demands upon her. A psychic sued for five percent of all moneys from her husband’s estate, on the ground that she had promised him that in case he brought about a reconciliation. He claimed he had affected the reconciliation. She said the “king” had died unreconciled to her. The battle waged in the courts, and battles in court always let money in lieu of blood.

Then came Mrs. Marguerite Gilbert with a disputed bill for $30,000 for “shadowing the children.”

Following the children kept her very busy. “Their father said they were ‘serving apprenticeship to folly,’” she testified.

“They were in resorts along Broadway and Sixth Avenue. Mrs. Adams could call me up and tell me the children were drinking and ask me to go after them.”

“How would you know where to look?” the lawyer for the other side asked Mrs. Gilbert.

“I would just keep going from one place to another until I located them,” was the reply. “I often did this until three o’clock in the morning. I used to try to have them brought home.

“I was to have three thousand a year,” said this family detective.

Now Walter Adams complains that he is bankrupt. His money has gone by way of Wall Street, he says. Clearly it has not returned to any of the poor from whom it was first filched.

Upon the heels of this news comes the other; that Richard Canfield is broke, that his daughter, divorced at eighteen, must go upon the stage to live.

Source: The Salt Lake tribune. (Salt Lake City, Utah), 05 Oct. 1913.