We don’t have to go far into European history to find torture and brutal executions that rival anything seen on Game of Thrones.

The article below, originally published in 1891, describes some of the more gruesome executions from that time period.

European Headsmen

Germany

The German executioner, Reindel, is the leader of headsmen on the continent. He is not a mere engineer of the guillotine, but strikes off with his own hand and trusty sword the head of the victim, after the fashion of hundreds of years ago. Beheading is the highest penalty for crime in Germany, and the headsman is kept fairly busy, going from one State to another on his hideous round. An execution in Germany today is not much different from those that we read about in English and French history, as to the common fate of political suspects.

The German criminal is handled more rudely, perhaps, than was King Charles or Lord Hastings, but in all essentials the modern German executioner’s work is like the old German.

Reindel’s most exciting experience was at Buckeburg, the capital of Schaumberg-Lippe, when he decapitated the notorious murderer, Heerwart. The case aroused a great sensation at the time. Heerwart was a refined ruffian, belonging to a good family, and in the habit of running in debt. People to whom he owed large amounts developed a different habit, that of dying suddenly, whereupon their administrators would find Heerwart in possession of a receipt recently signed for the sum supposed to be due. At last detection came and Heerwart was convicted and sentenced to death.

Reindel, who is a six-footer and a veteran soldier, arrived at the prison, accompanied by his three sons, who always act as his assistants. The courtyard of the prison was fitted up in the usual style, everything but the block draped in black, the block being covered with a bright scarlet cloth. Reindel never binds his victims. He depends upon his stalwart sons to hold them, and he had no reason to anticipate any resistance on the part of Heerwart, a middle-sized man, not apparently strong and whose conduct in prison had been excellent.

At the stroke of eight, the prisoner was led out, locked arm in arm with a prison officer. Heerwart’s eyes appeared to light on the block, and wandered from that to a table a few feet away, on which lay three broad swords, sharp and unsheathed, for the use of the headsman. With a leap, Heerwart was at the table and seizing one of the swords, he backed resolutely against the wall, in an attitude of defiance. Two of the sons of Reindel rushed upon him, and before he could use the weapon he was helpless in their grasp. It is hardly necessary to say that the formality of reading the death warrant was much abbreviated, and that the rest of the ceremony was brief. The three sons bore the prisoner to the block, two held him by the body, the other grasped his head. Reindel’s sword was, for an instant, poised in the air, then down it came, and the head rolled away, severed at one stroke. While crime, of course, varies, Reindel performs about thirty executions a year.

Austria

In Austria, criminals are put to death by strangling or shooting, according to the sentence of the Court. The gibbet is used at executions of the former kind, and Professor Sterneck, as he is called, the most noted of Austrian executioners, has been detected in practices very much resembling cruelty.

A few years ago he used to put an iron gag in the mouths of prisoners to prevent them from utterance. The practice had for a long time passed unobserved, until at length it was discovered by the slow going German newspapers. The “Professor” excused himself upon the ground of necessity, but he did not do it again. The shooting of criminals would have been altogether substituted for strangling, but for the objection on the part of soldiers to be detailed for any such purpose. This fact, and the reluctance to use the gibbet, have tended to bring about the virtual abolition of capital punishment in Austria, except in the worst cases.

Belgrade

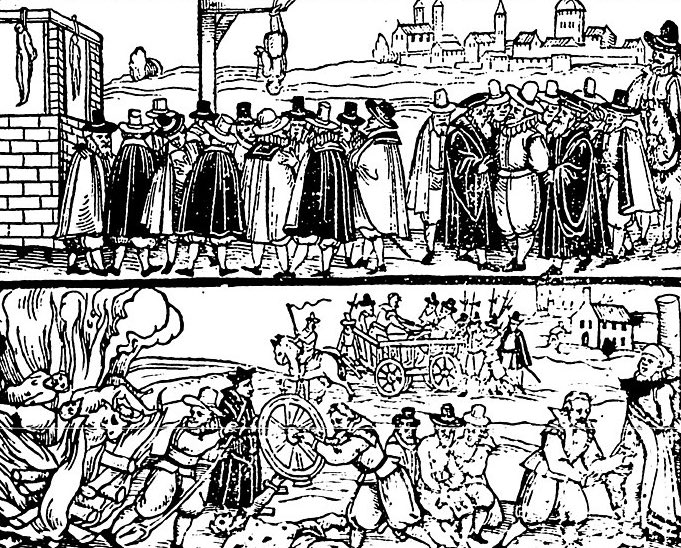

It may seem incredible, but it is true, nevertheless, that a retired executioner is living in Belgrade today, who, as late as 1875, broke criminals on the wheel. The name of the man is Paulo Jovanovitch, and the executions took place on the grassy slopes of the ramparts of Belgrade.

The most noted execution of the time was in 1872, when two men, one a Turk and the other a Hebrew, were put to death for murdering a whole family. The Hebrew was executed first, and fifteen minutes elapsed before the executioner gave him the coupe de grace.

The Turk made a violent resistance, and had to be stunned into subjection, although the stunning was, perhaps, unintentional. This medieval punishment was abolished about 1878, when Serbia asserted complete independence. Strangling in prison is the usual capital penalty.

Norway

In Norway an expert executioner is requisite, although his services are seldom needed. August Claeson is now an old man, and has held the office twenty-four years, with occasional assistance. The laws of Norway are still harsh in terms, and were harsh in practice not many years ago. Old man Claeson can remember that about twelve years ago a preacher named Jansen, convicted of murdering his child, stood in the pillory all day with his right hand cut off, and had his head cut off at sundown. Now, however, the punishment is decapitation, without the barbarous exhibition that used to precede it. The death penalty is so seldom resorted to in Sweden and Norway that it is practically obsolete.

Spain

Calleja, the Spanish executioner, who attends to the garrote in every part of the Kingdom where its use is necessary, has held office only three years. His predecessor, Robledo, was much better known.

Robledo was such an expert with the garrote that the Sultan of Morocco sent him a special invitation to go to that country and give evidence of his skill. Robledo went, out of humanity as he claimed, and suggested to the despot of the Moors several novel, but civilized, ideas to the infliction of capital punishment. It was the custom of the Moors to hack off heads with a knife. It was a tedious process, and calculated to cause pain to the subject of the experiment. Robledo succeeded in inducing the Sultan to substitute scimitars and dispense with the carving. Before the Spanish executioner left Fez, the Sultan invited him to witness a grand illustration of the proficient achieved by his men with the scimitar. Fifteen prisoners were beheaded in less than that number of minutes.

As to the garrote, public opinion, even in Spain, has long condemned the instrument as cruel, and it is only adhered to out of a Spanish reluctance for change.

Source: St. Landry democrat. (Opelousas, La.), 22 Aug. 1891.