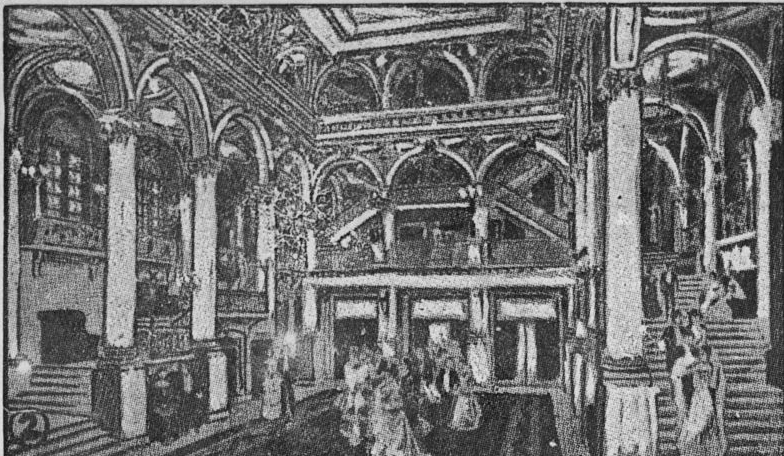

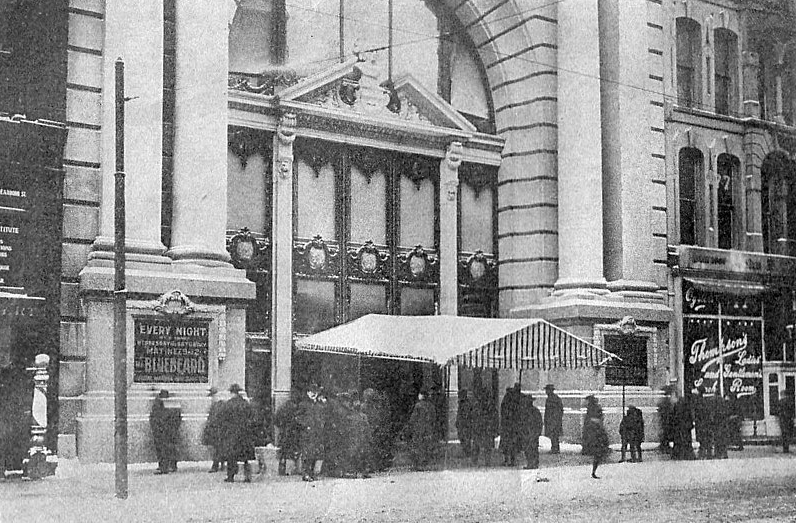

When the Iroquois Theater opened in Chicago on November 23, 1903, advertisers boasted that the building was completely fire-proof.

The building had a total of 27 exits (although the owners publicly claimed that the building had 30) and it was reported that if there was a fire, people would be able to evacuate the building within 5 minutes.

Furthermore, above the stage was a glass skylight. In theory, if a fire broke out on stage, the flames would go upward instead of towards the audience.

Before the theater officially opened, fire inspectors walked the building and found that most of the exit signs were missing and that some of the exit doors were hidden behind drapes, making it impossible for people to locate the doors in case of an emergency.

There was also no alarm system. If a fire would break out backstage, there was no way to alert anyone up front that there was a fire.

There were no sprinklers and no fire buckets. The building did not have enough hoses available if a fire were to break out.

Finally, the stage curtain, which should have been made entirely of asbestos, was only partly made of the fireproof material. The rest of the large curtain was made from wood pulp.

Like the unsinkable Titanic, it was only a matter of time before arrogance and lies brought about a terrible disaster.

On December 30th, a month after the theater opened, the theater was filled with nearly 2,000 people.

It was after 3 pm and the audience was watching a comedy called Mr. Bluebeard when one of the spotlights began to burn.

Embers began falling on the singers below. The performers grew nervous, but the audience was oblivious as to what was happening until the stage curtain burst into flames.

Everyone panicked. Patrons ran to where they thought the exits should be and found them locked and gated to prevent people from sneaking into the show.

Large mirrors hung on the walls and further disoriented the panicked crowd.

Some people made it to the unlocked exit doors but the doors opened inwards and the pressing crowd prevented those at these exits from pulling open the escapes.

Those who made it to the fire escapes found that they were unfinished and many people were pushed to their deaths below.

Then the lights went out and the theater went black.

People screamed and panicked even more. They trampled over the fallen and ran blindly into the darkness before the flames could reach them.

It took twenty minutes, and at the end, 602 people lost their lives.

Miss Anna Woodward, who had been seated on the second balcony, reported that there was a man who prevented her from opening the door to her escape. In her own words, she said,

“”I was in the second balcony and plainly saw the fire. I am a large woman, weighing close to 180 pounds, and I made up my mind that if there was going to be a panic it would be wise for me to beat it to the street. I left my seat in the balcony, went downstairs to the first balcony and from there started to pass out through the very door in which so many people were killed a few minutes later. The door was closed and a man standing on the outside refused to open it so that I could pass out. Whether he was an employee of the theater or not, I don’t know, but he had evidently determined that no one should leave the theater, and in so doing started a panic. I was leaving quietly up to this time, but when he refused to allow me to pass out peaceably I determined to get out if I had to make all sorts of noise.

“I went along the balcony about ten feet to a glass partition, and smashed it with the point of my umbrella. I went out and downstairs. When I was about half way down I heard the roar of the crowd as it came after me, and I hurried with all the speed I had. They overtook me, however, knocked me down, and, but for the fact that I was close to the door, I think my chance of life would have been almost nothing. As it was, I think I must have walked the last ten feet of my passage to the exit on the bodies of those who had fallen.” [4]

Miss Georgia Swift tried to rescue a young boy as she made her escape from the theater. She said:

“I started up the aisle at about the same time as all the others. My seat was on the first floor near the stage and when I had reached the rear of the auditorium the aisle was choked with people who had fallen. I looked down to avoid stepping on them and just as I did so my eyes were caught by those of a boy about seven years old, who was lying on the floor unable to rise. He had large brown eyes and was so neatly dressed and apparently so well bred that he fascinated me. It was all in a second, I know, but as he saw me looking at him, he said, ‘Won’t you please, please help me?’ I stooped to raise him, but the crowd was too thick and the rush too strong. I seized him under the arms and then I was knocked over him on my knees. I struggled to my feet, but the weight of the crowd was such that I could not turn back, and I was carried out through the door. The little boy was probably trampled to death and the memory of those eyes will haunt me while I live.” [5]

As people were trampled and burned inside the theater, there were many brave citizens on the outside, doing all that they could to help those trapped on the inside:

“Waiters and cooks from Thompson’s restaurant, which adjoins the theater on the east, rescued 15 people by raising a ladder from the roof of a shed to a window in the rear of the building, around which a mass of screaming women and children were congregated. The head cook mounted to the top of the ladder and told them to jump into his arms. Fifteen women and children did this and were passed by the head cook down to the other men on the ladder below him. One woman attempted to jump into his arms before he was ready to take hold of her and she fell to the alley, fracturing her skull. She died almost instantly.” [3]

Bishop Fallows was outside the theater when he saw the billowing smoke. Without fear, he went into the theater to save whoever he could. He said:

“God forbid that I ever again shall see such a heartrending sight. I have been in wars and on the bloody field of battle but in all my experience I have never seen anything half so gruesome as the sight that met my eyes when, with the aid of a tiny lantern, I was finally able to penetrate the inky darkness of that balcony. There was a pile of bleeding bodies ten feet high, with blackened faces and remnants of charred clothing clinging to them. Some were alive and moaning in their agony. Others – and oh! by far the greater number – were dead. I assisted in carrying many of the injured down and ministered to them the best I could.” [2]

When the firemen were finally able to enter the theater, what they witnessed was something that none of them were able to forget. One article stated that:

“…the dead were found stretched in a pile reaching from the head of the stairway, at least eight feet from the door, back to a point about five feet in the rear of the door.

“This mass of dead bodies in the center of the door reached to within two feet of the top of the passageway. All of the bodies at this point were women and children.

“The fight for life which must have taken place at these two points is something that is simply beyond human power to adequately describe. Only a faint idea of its horror could be derived from the bodies as they lay.

“Women on top of these masses of dead had been overtaken by death as they were crawling on their hands and knees over the bodies of those who had died before. Others lay with arms stretched out in the direction of safety, holding in their hands fragments of garments not their own. They were evidently torn from the clothing of others whom they had endeavored to pull down and trample under foot as they fought for their own lives.

“As the police removed layer after layer of dead in these doorways, the sight became too much even for police and firemen, hardened as they are to such sights, to endure. The bodies were in such an inextricable mass, and so tightly were they jammed between the sides of the door and the walls, that it was impossible to lift them one by one and carry them out. The only possible thing to do was to seize a limb or some other portion of the body and pull with main strength.

“Men worked at the task with tears running down their cheeks, and the sobs of the rescuers could be heard even in the hall below where this awful scene was being enacted.” [3]

Bodies had also been torn apart in the panic:

“There were scores and scores of people whose entire faces had been trampled completely off by the heels of those who rushed over them and in one aisle the body of a man was found with not a vestige of clothing, flesh, or bone remaining above his waist line. The upper portion of his body had been cut into pieces and carried away by the feet of those who trampled him. A search was made carefully with a hope of finding his head…” [3]

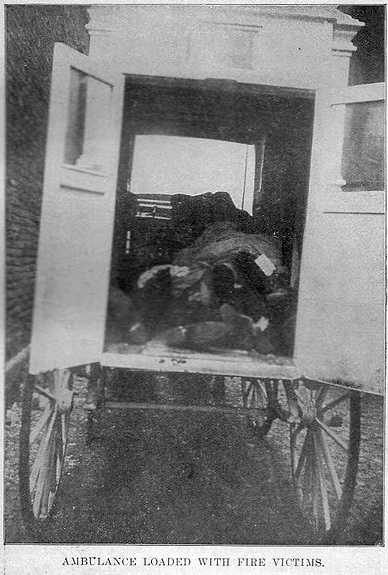

As the bodies were pulled out of the building, they lined the sidewalk. The bodies were laid side by side for fifty feet along the sidewalk and were piled two to three feet deep.

Every ambulance in the city was called to take the bodies to the morgues, but it wasn’t enough. Trucks were pressed into service and local dry goods stores donated blankets to wrap and carry the dead.

Several morgues were used to hold the remains of those lost to the fire, but the majority of the deceased were taken to the Rolston Morgue. It was there that a father identified the headless body of his 8-year-old son by the boy’s watch. A 14-year-old girl was identified by her father who carried a sample cloth of her skirt because many of the bodies were too disfigured and badly burned to be recognized by sight.

One father chose to take his little girl home instead of letting her be taken to the morgue:

“…a man, haggard and worn, entered a Cottage Grove Avenue car, carrying in his arms the body of a golden-haired girl. The form was partly wrapped in a canvas. As the father took a seat with the child in his arms, the conductor touched him on the shoulder, saying, ‘I am sorry, but the rules of the company do not permit the carrying of bodies in this manner. I must ask you to leave the car.’ Without changing his expression in the slightest, without showing a trace of excitement or irritation, the man rose to his feet still holding on one arm the body of his child. With his free hand he thrust into the face of the conductor a large revolver, and said in a tone which betokened utter weariness and nonchalance: “This is my daughter. I have looked for her all night and all day. I have tried in vain to obtain a cab or a carriage and I can get none. I am taking my baby home to her mother and I intend to take her on this car.” [5]

On January 1, 1904, just two days after the fire, it was reported that:

“For the first time since Chicago has possessed bells to peal, whistles to shriek and horns to blow, the old year was allowed to silently take its place in history and the new year permitted to come with no evidence of joy at its birth.

“The appalling calamity in the Iroquois Theater has cast Chicago into the deepest grief and gloom, and for the time being at least seems to have chilled and deadened all the ordinary ambitions of life. Business today was performed with the sole view to actual necessity, and even that much was carried out in a perfunctory manner.

“Ordinarily on New Year’s Eve the streets of the city are filled with merrymakers, but tonight the only throngs to be found were those around the morgues. Ordinarily, numbers of fashionable restaurants in the heart of the city are filled with light-hearted revelers who toast the year that passes and hail the year that comes. Tonight these places were deserted, and some of them closed entirely, with doors locked and curtains drawn.” [4]