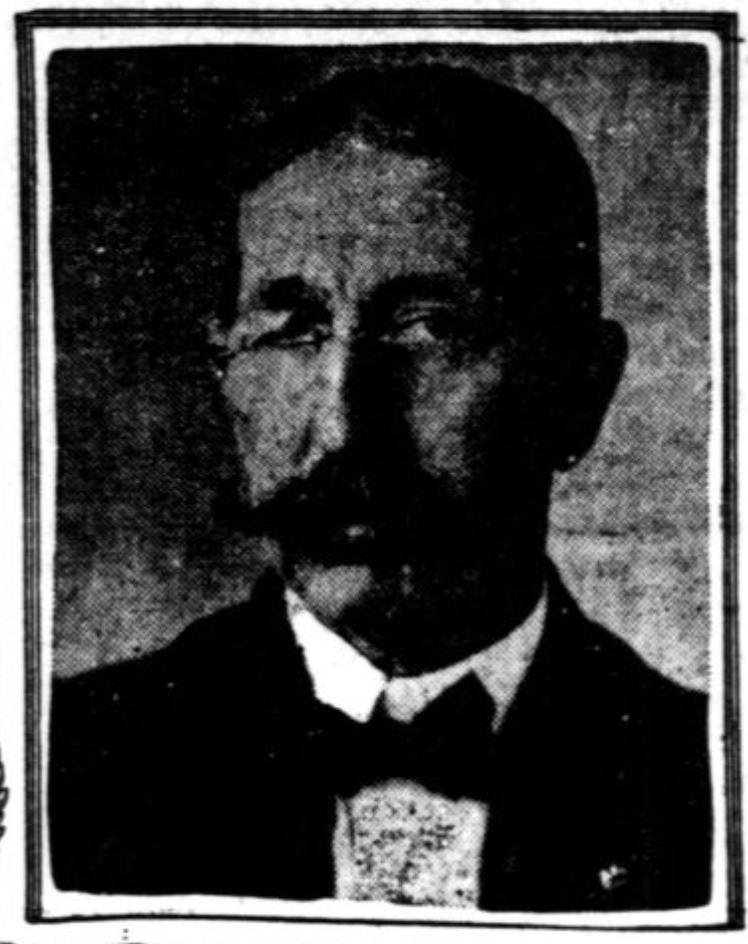

Hi everyone. This is Elizabeth from Strange Ago. Today I want to share with you some of the research I’ve been doing into a man named William Schoneberger.

Before I begin, there was some issue with the spelling of William’s last name. In the employment logs from that period, his name is spelled with an “oen. ” However, in some newspaper reports, his name is spelled with “one.”

Update: I was contacted by the great-granddaughter of William Schoneberger and she confirmed the correct spelling of his name. (April 1, 2022)

And so, while I was researching the history of American morgues in the newspaper archives, I began finding multiple articles about Morguemaster Schoneberger in Washington, D.C. But, unfortunately, a Google search on this morgue master turned up nothing. He wasn’t even listed on Wikipedia. So I knew I had a lot of digging to do through newspaper articles.

Childhood

Originally born in Washington, D.C., in 1863, Schoneberger was taken to the country to be reared. At the age of 7, his father died, and he was sent to work on a farm for 9 years. At age 17, he returned to D.C. and became a butcher.

He married and had children. Then he became a janitor of the No. 6 police station, and one year later, on July 15, 1892, he was placed in charge of the morgue. It was there that he became known to all as the Morguemaster. He was the first of his kind in the District of Columbia.

The Early Morgue

When Schoneberger began his work as morgue master, morgues were situated inside the police stations. However, the smell of decomposing bodies stank up the neighborhoods close to the stations.

After numerous complaints from the neighbors, the bodies were housed in a small apartment at the rear of the No. 6 police station. But this certainly wasn’t good enough.

As one report explained, “In those days, the dead were removed in vehicles of many kinds to the back yards of the several police stations. If there was a stable attached to the station house, it was used as a temporary morgue. If not, the remains were placed in the open yards and covered with canvas. The effect in the neighborhood of the police station after a decomposed corpse was brought in can be better imagined than described.”

The space was cramped, with only room for four bodies at a time. After any disaster with a large body count, bodies had to be stacked one on top of the other.

There was no running water, and when water was needed to wash the bodies, it had to be gotten from the stables. And again, the smells from the morgue disturbed the neighbors.

There was no modern ventilation. On several occasions, the policemen in the adjoining station house were made sick by the extreme odors, especially the smell from bodies that had spent some time in the water.

Rats were a problem.

One gentleman commented, “It is sacrilegious for the authorities to provide such a place for the reception of the remains of those unfortunates, who met their deaths by accident or homicide. I wouldn’t keep the body of a dead pet dog in such a place.”

The only solution was to build a new morgue.

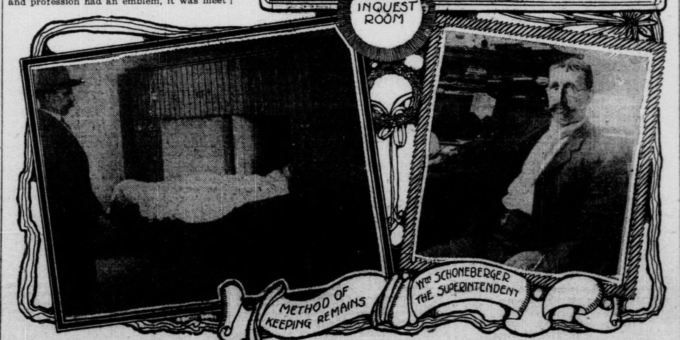

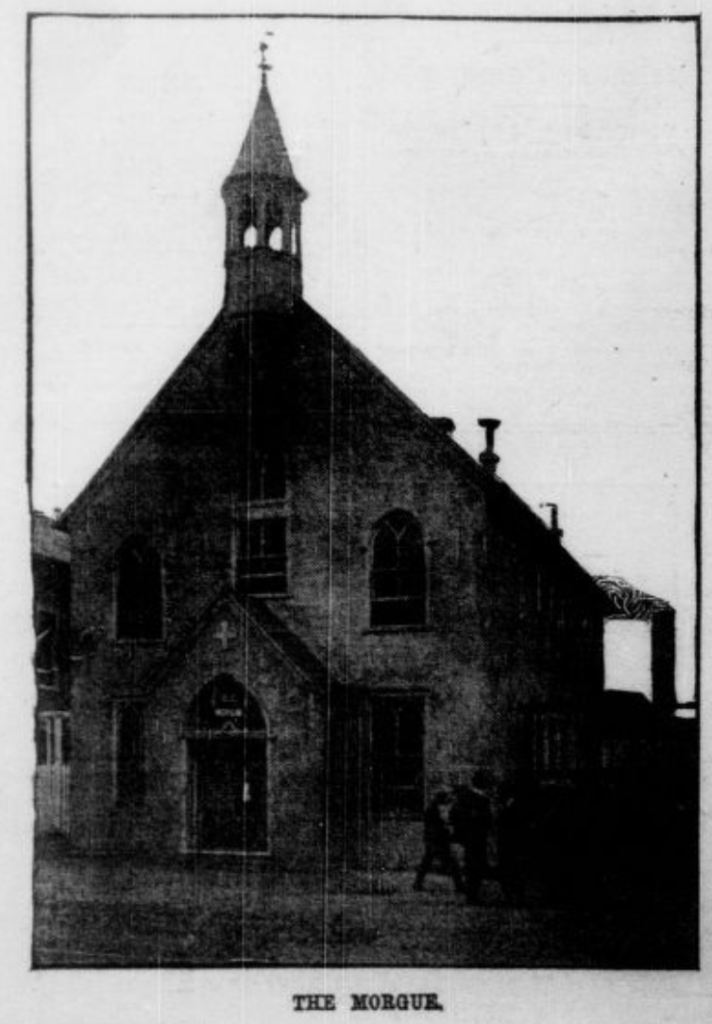

The New Morgue

To raise money for a new morgue, Schoneberger, along with police reporters, began to call attention to the deplorable condition of the morgue. After the public outcry, Congress set money aside for the new building.

And in July 1904, the new morgue was complete and ready for occupation. It had 10 vaults where bodies could be kept on ice until claimed, taken to Potter’s field, or sent to a medical college for dissection.

There was a room where the clothing of the dead was hung and ventilated. And an inquest room where juries decided on whether a death was homicide or accidental. There was even a prison cell inside the morgue where a person could be held during murder inquests.

At the front of the morgue was the office occupied by the coroner, Nevitt, and Morguemaster Schoneberger. The autopsy room on the upper floor was considered one of the best in the U.S. during the period.

There was also a small anatomical museum, something that Schoneberger arranged, where items of interest to anatomists and medical doctors were held. The museum included an infant that had been mummified by Schoneberger.

Record Keeping

Schoneberger claimed that he perfected the morgue’s system of record-keeping. This effectiveness in record keeping and evidence collection was proven in 1905.

As was reported, in 1904, the body of a man was brought to the morgue. Unfortunately, no one knew the man’s identity, so Schoneberger kept the body in the morgue for 45 days before being buried in Potter’s field.

Roughly a year later, the man’s mother came to the morgue to find out what had happened to her son. She had sent letters out all across the United States to find him, and now, as a last attempt to discover what might have happened to him, she spoke to Schoneberger.

Schoneberger kept descriptive notes of all who entered the morgue. When a body could not be identified, he always kept a piece of the deceased person’s clothing and any other items that were on the body.

The mother recognized the coat fabric held by Schoneberger and was able to have her son’s body removed from Potter’s field and shipped to his birth town.

In a 1919 article, Schoneberger said, “I have been a morgue keeper since 1892, and during that time, I have seen bodies identified by many methods. Little trinkets, keys, fountain pens, scars, and many other things have resulted in the identifications.

“And many a family rested after weeks and years of anxiety over the disappearance of a dear one. While the news of death is shocking, there seems to be a lot of satisfaction to the relatives when they find the bodies have been buried and that they can reclaim and properly and decently bury them in the family cemeteries.”

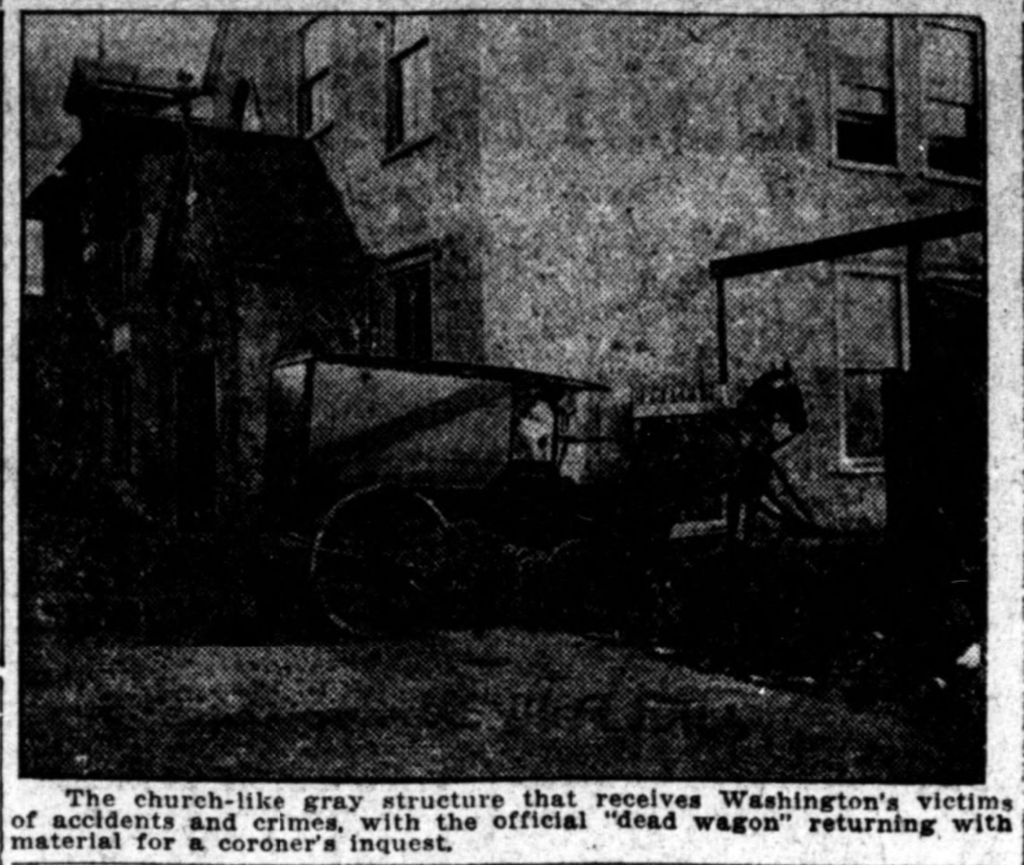

Morgue Wagon

With the new morgue came the idea for a morgue wagon. Previous to the morgue having its own wagon, the police patrol wagons were charged with bringing the dead to the morgue. Many policemen found this duty objectionable, so the morgue obtained its own wagon for this purpose.

Schoneberger’s Professional Emblem

It was custom that every profession have its own emblem. So people asked Schoneberger what his emblem was for the role of morgue master.

He gave the matter some thought and had a pin designed.

It was, of course, a skull and crossbones. Each eye of the head held a glittery green emerald that some found to be unearthly and unsettling.

He proudly wore the pin on his scarf with just a touch of humor. He even had the emblem printed on his business cards.

The man was known for sharing jokes among friends and had a friendly disposition for the most part.

His Favorite Story

One of his favorite stories to tell was of a time the police brought a dead body to the old morgue behind the police station. The body was placed on a slab, and as Schoneberger began to search the man’s pockets for some form of identification, the dead man groaned, moved his hand, and then sat straight up.

Completely taken aback, Schoneberger ran into the police station for help. Still, by the time they got back to the morgue, the dead man had left, and he and the officers never found out who the man was.

Court Cases

Schoneberger was often called to testify in court cases.

In May 1898, he testified during the Canty murder case that the victim was brought to the morgue. First, he identified the victim’s clothing and shoes. Then he identified the items found in the victim’s pockets and stated that a bullet fell from one of the victim’s trouser legs.

In November 1903, we find that Schoneberger testified in an inquiry regarding the death of Albert Beckwith.

Beckwith’s body had been discovered on a sidewalk in what appeared to be a deadly robbery. However, Schoneberger testified that he noticed that the pockets had been turned out when he arrived on the scene. In addition, there was very little blood under the victim’s wound.

Schoneberger felt that the man had been murdered elsewhere and was then dumped on the sidewalk based on his observations.

Controversy

Schoneberger’s only controversy came to light in 1913 when it was reported that not all of the bodies that went on to Potter’s field were given religious ceremonies.

As one article stated, “it is the practice to bury unidentified bodies left at the morgue without religious services.”

Schoneberger denied this accusation and said, “Since July 1, 1910, Christian services have been held over the bodies of 1,140 adults and children. Practically all of the bodies receive Christian rites, and only a few are buried without ceremony. It is only in cases where the minister who was asked to officiate does not appear that the body is buried without the service.”

There were two ministers on-call for white people and two on-call for people of color.

There is plenty of evidence that proper burials were given to the unknown. For example, in 1907, there was a railroad accident at Terra Cotta. The multiple remains, all mangled bits, were placed in a large coffin and interred at a local cemetery with routine care.

Schoneberger also began cremating bodies of the unwanted in 1910.

Death

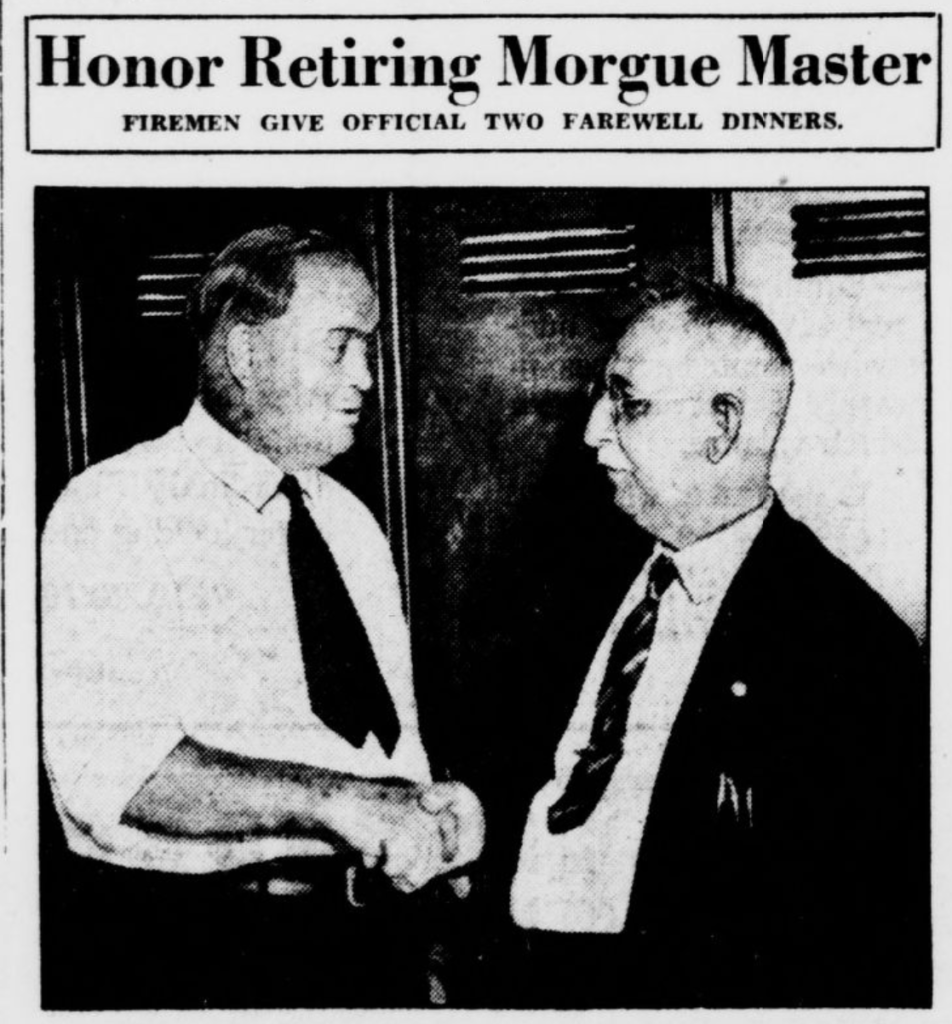

After completing 42 years of service as master of the morgue, Schoneberger retired in 1934.

He passed away on Saturday, December 27, 1941. He was survived by his widow, three daughters, and a son.

Sources:

1. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 05 Aug. 1906.

2. The times. (Washington, D.C.), 18 May 1898.

3. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 17 Nov. 1903.

4. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 15 June 1904.

5. The Washington times. (Washington, D.C.), 15 Feb. 1913.

6. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 15 Feb. 1913.

7. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 03 Jan. 1907.

8. The Washington times. (Washington, D.C.), 16 Nov. 1905.

9. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 16 Oct. 1938.

10. Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 29 Dec. 1941.

11. The evening times. (Washington, D.C.), 07 Nov. 1896.

12. The Washington times. (Washington, D.C.), 18 May 1919.

13. The Washington herald. (Washington, D.C.), 18 Aug. 1918.