Barbecue, a cooking technique that involves slow-cooking meat over low heat, has a rich history that spans thousands of years.

The origins of barbecue can be traced back to indigenous peoples in the Americas who used smoke to preserve meat.

In the 16th century, when European explorers arrived in the Americas, they brought with them the concept of cooking meat over fire, which was combined with the indigenous method of using smoke to create what we now know as barbecue.

As the practice of barbecue spread throughout the world, it took on different forms and flavors. In the Southern United States, barbecue became a staple food, with each state developing its own unique style and flavors. Texas, for example, is known for its beef barbecue, while North Carolina is famous for its pulled pork.

During the 20th century, barbecue gained popularity as a competitive sport, with competitions taking place across the United States. In the late 1900s, barbecue restaurants and barbecue sauce companies began to emerge, further popularizing the cuisine.

A more in-depth account on the politics behind the barbecue’s popularity can be found in William S. Walsh’s Curiosities of Popular Customs and of Rites, Ceremonies, Observances, and Miscellaneous Antiquities (1925) below:

Barbecue

From Sp. barbacoa, an attempt to transliterate a native Haitian term for a wooden framework supporting meat or fish to be smoked or dried over a fire. In its most popular modern signification, a large social or political entertainment in the open air, at which sheep or oxen are roasted whole and all the feasting is conducted on a Gargantuan scale.

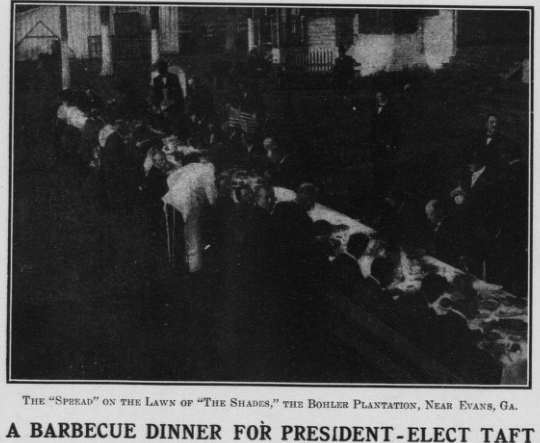

Georgia is probably the native home of the barbecue, but it spread thence to most of the Southern and Southwestern States, and has even invaded some of the Northern ones. Georgia, however, still retains its supremacy as the Barbecue State.

“The barbecue is to Georgia,” says D. Allen Willey, in the Home-Maker’s Magazine for December, 1896, “what the clambake is to Rhode Island, what a roast beef dinner is to our English cousins, what canvas back duck is to the Marylander, and what a pork and beans supper is to the Bostonian. The barbecue has done much for Georgia. It has played its part in politics, in social gatherings, in the entertainment of strangers, and in festivities generally. It has come to be a necessary part of all kinds of social functions, and the man who has visited Georgia and come away without a sample of barbecue viands is indeed to be commiserated.

“The genius who prepared the first barbecue is unknown, although there are a dozen theories offered as to its origin. Get into a country store and sit on the cracker-box by the side of two or three Georgia ‘colonels’ and ‘majors,’ and they will tell any number of tales about how their ancestors bought their estates from the Indians and to close up the bargain gave the ‘noble red men’ a barbecue consisting of venison and sweetened hoe-cake, followed by plenty of imported rum and other ‘fire-waters.’ One thing is clear, and that is that game constituted the meat cooked in the barbecue of fifty years ago. As deer, bear, and other animals became scarce, oxen, sheep, and pigs took their places. The variety of viands increased until the barbecue of today may contain fish, beef, mutton, pork, vegetables, and fowls. It depends much on the liberality of the givers and the number invited to participate. The popularity of this kind of entertainment is so great that it is enjoyed in cities as well as towns. Even in the wire-grass country, where possibly the white farmers live two or three miles apart, a half dozen families will get together on a holiday, or some one’s birthday, perhaps kill a sheep or a pig, and have a barbecue. During the Atlanta Exposition a daily barbecue, at which three or four hundred persons were fed at once, was a feature.

“As an aid to political campaigns, the barbecue exerts a powerful influence. Many a man has been elected senator, or governor, or Congressman from this State by a majority secured largely through votes gained at barbecues. A canvass for the governorship of Georgia is not considered completed without a series of these affairs, sometimes one in every county, given just before election, to which every one is invited.”

In other Southern and Western States the barbecue plays its part in the political game; and it is not entirely unknown in New York. It was first introduced into that State in the Presidential campaign of 1876 by Republican managers, and the example so set has since been followed occasionally by members of both the great parties.

On the morning of Wednesday, October 18, 1876, two huge oxen were paraded through the cities of New York and Brooklyn and then taken to Myrtle Park in the latter city.

There they were killed in the afternoon. By eleven in the evening one weighing 983 pounds was on the spit and in process of roasting over a coke fire. Though less picturesque that the old fashioned pit, with its wood fire, its forked flames, and occasionally its superabundant smoke, this was found to be an improvement as a cooking apparatus. The coke fire was placed in two large iron pans, ranged parallel to the spit, but not directly under the carcass, the heat being thrown on that by a peaked roof of the same metal stretched over the spit and about two feet from it. Between the two fires was a long dripping pan, from which the meat was frequently basted with its own fat. The first ox was declared done at eight o’clock on Thursday morning (October 20), and was taken off to cool, while the other, over 1,000 pounds in weight, took its place upon the spit. Even at that early hour some hundred or more curious citizens were on the ground, and the number kept steadily increasing until by noon over a thousand had arrived. The barbecue was then declared open. All present were invited to a share of the ox which had been roasted during the morning. This had been cut up and with the aid of 800 loaves of bread turned into sandwiches. So great was the public demand that in twenty minutes the only vestiges left were the skeleton and such fragments as were unfit for food. The other ox was served up at night. Upwards of 50,000 people in all participated in the exercises. Five speakers, at al many stands, simultaneously addressed audiences of thousands, while thousands more amused themselves in various ways in the grounds.