If you are fascinated by old tales of hidden gold, then you have probably heard of the search for Montezuma’s gold.

Montezuma II was the ninth Aztec emperor of Mexico, who ruled from 1502 until his death in 1520. He was the last of the Aztec emperors and his reign saw the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés, who eventually conquered the Aztec empire.

Knowing that the Spanish conquistadors were after his riches, the legend of Montezuma’s gold tells us that the emperor hid his immense wealth of gold, silver, and jewels before his death.

Because the treasure has never been found, the search for Montezuma’s gold continues to this day, with many people searching for it in different locations throughout Mexico, including the ancient Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán, now Mexico City.

Some have also searched for it in the United States. Despite the many attempts, the gold remains one of the greatest mysteries of history.

Below is an article, published in 1945, about those who have searched for the treasure.

Long Trail to End of the Aztec Rainbow

For more than four centuries the treasure of Montezuma – the vast hoard of gold that the Aztec emperor is presumed to have hidden from the Spanish conquistadors – has been sought in various nooks and crannies of North and Central America.

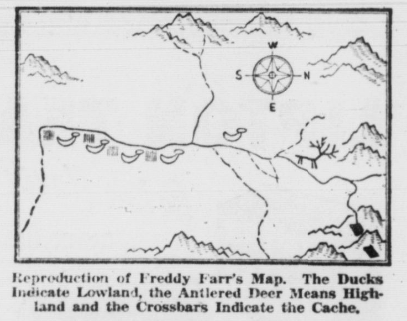

One of the most recent searchers, and the one who probably holds the long distance record in this particular pastime, was Freddy Farr, a sun-baked old protector who spent seven years following a trail of pictures indicated on a time-marked map. Farr found disappointment instead of a pot of gold at the end of the Aztec rainbow.

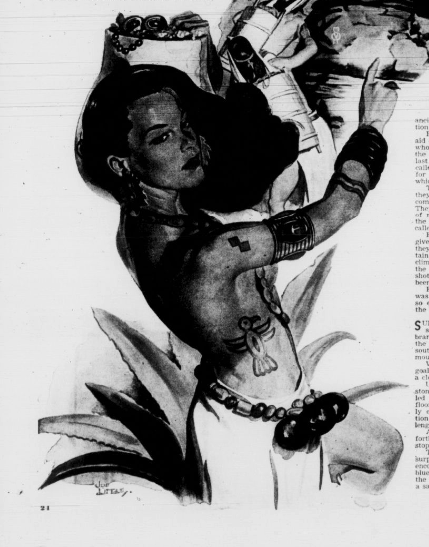

Farr had spent months in Mexico studying Aztec petroglyphs – symbols carved in rock – and then, armed with his map and information for which he had paid considerable money, he began to look for the gold trail. After a long hunt, he found a petroglyph on a cliff. A little further along there was another, and then another.

It took Freddy seven years to follow the picture clues up through Mexico and Texas into Arizona. There he lost the trail and finally he gave up. Months later, he was reading a magazine in a barber shop in Las Vegas, Nev. Suddenly he jumped up, shouting “I’ve got it! I’ve got it!” While the barber stared in amazement, he ran out of the place, clutching the magazine.

What Freddy had seen were some pictures of petroglyphs found by a professor near Kanab, an isolated Mormon settlement in Utah. To most people they were merely interesting relics of an ancient race, but to Freddy they were a resumption of the trail he sought.

He made his way to Kanab and enlisted the aid of Levi Lawson, a hardheaded young rancher who thought treasure hunting might be fun after the fall roundup was out of the way. When the last maverick had been caught and branded, Levi called his cowboys together and told them to look for a certain pattern of peaks and valleys near which the gold would be hidden in a sealed tunnel.

The cowboys made a lark out of it. For weeks they rode over the wild range country seeking a combination which would open the Aztec safe. They forced their weary mounts over hundreds of mountain ranges, but nowhere did they find the topographical arrangement that the map called for. Finally Lawson called the search off.

Freddy was discouraged, but he hadn’t quite given up. As they neared the Lawson property, they passed by a high ridge called Sheep Mountain. The old prospector turned his horse and climbed up the slope for a last look. A little later the rest of the party heard a series of pistol shots – the signal that something interesting had been located. They wheeled and raced back.

Freddy was on top of the bare ridge. His map was spread out on a rock before him. He was so excited he couldn’t talk, but he pointed and the rest of them looked.

Sure enough, it was the pattern they were seeking – the main canyon with the side draws branching off, the mountains to the east and west, the four peaks to the north and the one to the south. On the map the trail ended at the third mountain to the northeast.

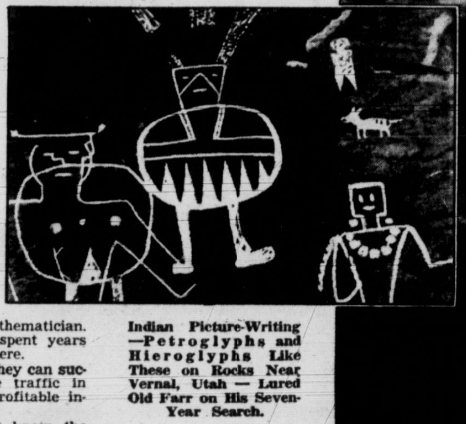

With wild whoops the riders started for their goal and after 14 miles, they found themselves in a clearing in front of a sandstone cliff.

Up the face of the cliff, carved into the sandstone, was a series of niches, like footsteps, which led to a ledge about 500 feet above the valley floor. The men scrambled up the steps and eagerly explored the shelf, looking for some indication of a tunnel. There was none. For the full length of the ledge the cliff stretched solidly.

Almost in a trance, Freddy paced back and forth, scanning the bleak bluff. Suddenly he stopped, pointed and said “Let’s dig here.”

The picks cut into the sandstone, which was surprisingly soft, but after a foot or so they encountered something hard. It was a wall of blue limestone blocks, connected together. Over the face of the wall Indian artisans had spread a sand plaster which was a perfect match for the surrounding sandstone. Only Freddy had noticed the difference.

The limestone shattered under the biting blows of the picks and the men broke into a tunnel large enough to enter erect. They lighted candles and forged ahead. After about 80 feet they came across the remains of a fire with deer and rabbit bones. Even more excited, they pushed on to the end of the tunnel and found that it branched off into four large caverns.

Here was the ideal hiding place for a golden hoard – but there wasn’t even a fleck of gold dust to be found. They tapped, probed, and even blasted, and they just wasted their time. If Freddy Farr had been sold a completely phony map, he had chanced upon a coincidence that would baffle any odds-figuring mathematician. And yet, like many others, he had spent years at strenuous effort only to get nowhere.

Because most men are convinced they can succeed where others have failed, the traffic in treasure maps has become a very profitable industry south of the Rio Grande.

If you have enough money and know the right people, you can buy in almost any part of Mexico a map which will show you the exact spot in which a large chunk of Montezuma’s millions was hidden. Usually these charts look very authentic, particularly if the price is high enough. They are drawn on old Aztec paper – or a reasonable facsimile – and the art work strikingly resembles the picture symbolism of Aztec cartographers.

You get an extremely convincing sales talk, too. In a sibilant whisper the map owner will tell you that when Montezuma realized that gold was what the invaders were seeking he dispatched caravans to various points to hide as much of the yellow metal as possible.

As he talks, you can almost see the wealth of a powerful nation being transported into hiding. Worming its way along a narrow road comes a long line of Indians, tlamemes (carriers), each capable of carrying 22 pounds for 22 miles a day. They move slowly, their heads bent slightly earthward, held rigid by the flat mecapalli (strap) that stretches across their foreheads to clamp the precious cargo on their backs.

They are dressed simply, a breech clout – maxtl – wound about the waist, their long black hair hanging in a single braid. At the head and tail of the line are the emperor’s trusted agents, wearing swirling embroidered robes and squeaking jaguar-skin sandals. And on both sides march the Aztec soldiers, watching warily.

This view of 100 or more tlamemes, each toting some $11,500 on his back, is enough to inspire the most phlegmatic treasure hunter in the world.

Oddly enough, although perhaps for good reason, the hidden gold is rarely sought anywhere near Mexico City, the spot from which it would originally have been dispatched. Most of the maps indicate mountain carriers. Some show lakes in which the furtive carriers were supposed to have dumped their cargoes. Others vaguely locate the treasure in the weather-beaten stone pyramids which dot the jungles of Central America.

The first seekers of Montezuma’s wealth were, of course, the Spaniards. There is a statue in Mexico City showing Cuauhtemoc, Montezuma’s successor, and the Lord of Tacuba, one of his nobles, being tortured by the conquistadors in an effort to extract from him the secret of the vanished fortune.

Their feet have been soaked in oil and set afire, and the Lords of Tacuba is pleading with Cuauhtemoc to tell where the riches are and put an end to his pain. Etched in stone is the emperor’s calm answer: “Am I taking my pleasure in my bath?”

Hernán Cortés and his men did manage to get away with enough gold to put an envious sparkle in the eyes of avaricious Europeans, but their loot was comparatively puny in a country in which gold dishes and plates were common.

Because religion played such an important part in the lives of the Aztecs, many treasure hunters have pinned their faith on maps which indicated that part of Montezuma’s hidden wealth was cached within the ruins of pyramidal temples.

That may be true, and the man who perhaps could have verified it was never willing to do much talking. He was an English officer, Captain John Carmichael, who was stationed in British Honduras. One day he saved the lives of a native father and son. In gratitude they gave him two curious golden ornaments.

Questioned, they said the ornaments were badges or tokens carried by the guardians of a secret temple in which several centuries ago a treasure had been hidden from the Spaniards. The temple was located in a great swamp north of Tikal in Guatemala, and was inaccessible, they said, to anyone who did not know the path.

Captain Carmichael persuaded them to take him there. He swore that he was interested only in the archaeological value of the building and that he would never go there again.

He apparently kept his promise for 25 years, and then, flat broke, he persuaded two wealthy Americans to finance an expedition. First he was unable to find the path but returned the following year, got malaria and had to abandon the effort.

Undaunted, he made a third attempt a year later. He entered the great swamp with several native carriers, never to be seen again.

One shrewd Mexican profited highly from the gold-hunting fever. He had a lake near the edge of his property that he wanted drained, but he didn’t want to spend the money for a canal to do the job. He hired an artist to draw, on a piece of goatskin, a map which any astute observer might take to indicate that some of the missing treasure had been dumped into his lake. After allowing it to weather for a while, he put it in a suitcase with some old clothes and left the suitcases in a Los Angeles railroad station.

As he anticipated, a stranger approached him a few weeks later and offered to buy a lake. He sold it, with apparent reluctance, for considerably more than it was worth and then sat back to await developments. Before long, a steam shovel and a crew of men were busily engaged in digging a canal. The lake was drained and the bottom was scraped, but all that appeared was some rich black mud. It turned out to be very fertile when, some months afterward, he bought back his property for a song from the Los Angeles syndicate which had financed the draining operation.

As far as the world knows, Montezuma’s treasure is still intact. To be sure, some $5,000,000 in gold has been taken from the sacred pool, or denote, in ancient Chechen Itza, but most archaeologists agree that this wealth belonged to the Mayans and not the Aztecs.

Some day, perhaps soon, a large chunk of the Aztec hoard may be found in a cavern or lake or temple – but probably not with the aid of a map.

Source: Detroit evening times. (Detroit, Mich), 26 Aug. 1945.