I absolutely love reading old science theories that would be thrown out by the stifling, uncreative minds that seem to fill our world today. Sometimes I imagine such greats as Ray Bradbury or Harlan Ellison reading an article like the one below and being inspired to write a short work of science “fiction.”

If the below article, originally published in 1922, seems a bit too long to read at the moment, then here is one of the best lines from it:

“Lord Kelvin based his hypothesis that all life was originally brought to this earth from other planets in meteor forms which brought not only fossils but living germs.”

Wow!

Amazing Proof From the Sky of Life on Other Planets

By Dr. W. H. Ballou

Does life exist on other planets?

This fascinating problem of the universe, which has intrigued the mind of man for thousands of years, has at last been answered definitely in the affirmative, according to the belief of leading scientists.

The astonishing discovery had just been communicated to the world by Dr. Galippe, the distinguished laureate of the French Academy of Science and Academy of Medicine.

Aided by his famous colleague, Dr. Soufflaud, he has completed a series of experiments which he believes yield convincing proof of the existence of fossil forms – of both animal and vegetable life – imbedded in certain meteorites which have fallen to earth from the sky.

All children know what a meteorite is. They have a more picturesque name for it. They call it a “shooting star.” Dozens of times you have seen one of them shooting earthward through the summer night. Of course, it isn’t really a shooting star. It isn’t a star at all. It is a chunk of black rock which has been flung off from some celestial body, and which comes hurtling through space for millions of miles.

During the first part of its journey it would be invisible, even if you were close enough to think you might catch a glimpse of it – for it is cold and dead.

It is only when it enters the earth’s atmosphere – composed of oxygen and hydrogen – that it takes fire from the friction caused by its immense speed and blazes into view as a fall of fire.

Friction ceases when it strikes the earth and it becomes black and cold again. While it is falling it is called a meteor. After it has hit the earth it is called a meteorite.

There are thousands of them. You can see them in any natural museum.

When meteors first began to be examined scientifically, observers were content to discover that they were composed of “igneous rock” – that is, mineral matter which had been fused by subjection to intense heat.

But meteors were too interesting for observers to be long content with that simple fact. They were – and still are – the only “messages” which the earth receives from the other stars or planets (with the exception of light waves), for several generations the best scientific minds have been engaged in the fascinating pursuit of further deciphering these “letters” from other worlds.

For a long time the subject of just how much could be learned from these meteorites has been controversial – and to some extent is still so – but the latest discoveries by Galippe and Soufflaud are, in the writer’s opinion, convincing proof that life actually exists, or did exist, somewhere out there in illimitable space.

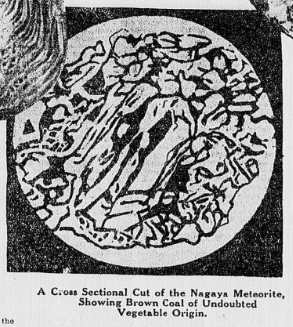

The experiments have involved the most exacting microscopic and chemical analyses. Under these the meteorites have revealed not only the mineralized forms of such lower animals as the crinoids – to which the starfish and the sea urchin belong – corals and sponges, but peat and coal, as well. Peat and coal, as you know, are of vegetable origin.

Furthermore, in some of these meteorites traces of water have been found and in others, oxygen.

These discoveries imbedded in the stony masses form a message compact, unequivocal and startling. They show not only that life exists somewhere “out there” in the world they have been torn from, but also that the world “out there” must have been, in some respects, like our own.

The crinoids, sponges, and corals, much like the same formations we still have on this earth today, prove that this other world possessed an ocean; the peat and coal, that it had vegetation and probably forests; the water and oxygen, that it possessed an atmosphere.

Where rolled the world of which the meteorite was a part? What ruled it – creatures comparable to man, lower forms, higher forms, or strange shapes produced by processes of evolution unknown to us here?

And what happened to that world?

Such things can be guessed at only.

As to what its life forms were, two things seem reasonable sure. One is that they resembled in some degree those we know on earth. This is indicated by the similarity of the crinoid fossils to our own crinoid forms, and by the presence of water and oxygen showing that the conditions were to some extent like our own.

The other thing we can believe with reasonable certainty is that while they resembled our forms in some respect they differed widely in others, for the conditions in which they underwent their long evolutionary processes must have been alike in some ways, different in others.

The artist who has made the large drawing on this page gives you an idea of what you might expect if you visited another of these inhabited planets. You would probably see forms which reminded you of things you had seen on earth, but weirdly and fantastically different, as in a nightmare or fairy tale.

You would almost certainly see forms of life that resembled to some extent our vegetables – living things fastened by their roots – and living things with power of locomotion that would remind you in a fantastic way of our own animals.

You might or might not need the helmets and oxygen tanks which the artist has provided his men in the drawing – depending on whether the atmosphere was like our own or different from it. Some kind of atmosphere there would have to be, else there could be no life. The exact detail, of course, is purely imaginative.

The most extraordinary and most discussed single meteorite that ever came to earth is the famous “Knyahinya” – so called from the name of the Hungarian town near where it fell. It is also known as the Hahn meteor, because of the exhaustive study of it made by Dr. Otto Han, geologist and physicist of the University of Vienna.

According to his views and those of other German scientific men, this meteorite was largely composed of fossil animals and plants. This, of course, was in a past generation.

The greatest minds of the nineteenth century were divided on this blazer.

Lord Kelvin based his hypothesis that all life was originally brought to this earth from other planets in meteor forms which brought not only fossils but living germs.

I have no brief to hold for Hahn or his meteorite. In that particular case the subject was, and still is, controversial. Many leading scientists have refused to accept his thesis and have insisted that the alleged fossil forms described were merely peculiar crystallizations of silicate minerals.

But a repudiation of Herr Hahn does not dispose of the subject. Galippe and Soufflaud, in France, working today with much more modern laboratory facilities and with meteorites which are in no way connected with the one which fell in Hungary, have come to conclusions even more startling than those of Hahn.

These conclusions, which have been formally communicated to the French Academy of Science, are the basis on which leading scientific men today – though not all scientific men – now accept the belief that some form of life actually exists on other planets than our own little earth.

Source: Richmond times-dispatch. (Richmond, Va.), 02 July 1922.