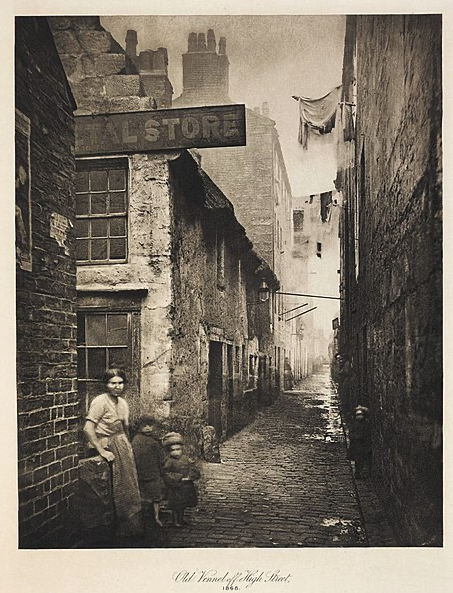

During Victorian England, the treatment of syphilis was rudimentary and often ineffective, reflecting the limited medical knowledge of the time.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum, was a major health concern and carried significant social stigma.

However, the treatments were just as scary as the disease itself.

Mercury Treatment

The most common treatment for syphilis during the Victorian era was mercury.

Mercury could be administered in various forms, including topical ointments, ingestion, or fumigation, where the patient was placed in a closed cabinet filled with mercury vapor.

The vapor treatment was based on the theory of humorism, which believed diseases were caused by imbalances in body fluids. Mercury was thought to help rebalance these humors.

However, mercury treatment was toxic and could cause severe side effects like tooth loss, ulcerations, neurological damage, and even death.

Iodine and Arsenic

Other elements used included iodine and arsenic. These treatments were also toxic and provided inconsistent results.

Like mercury, the use of arsenic became more popular in the late Victorian era with the introduction of “Fowler’s solution,” a potassium arsenite solution.

Guaiacum

This was a less common treatment derived from the wood of the guaiac tree. It was believed to have curative properties and was administered as a tea or tincture.

Surgical Interventions

In some cases, surgical interventions were used to remove syphilitic growths or to relieve pressure on the brain in cases of neurosyphilis.

Hygienic and Dietary Measures

Doctors also recommended various hygienic, dietary, and moral interventions, reflecting the belief that syphilis was not only a physical ailment but also a moral one.

The turning point in the treatment of syphilis came in the early 20th century with the development of Salvarsan, a more effective arsenic-based drug, by Paul Ehrlich in 1909.

This was later replaced by penicillin in the mid-20th century, which remains the effective treatment for syphilis today.